5 Elegant Song Dynasty Beizi Fashion Styles

Song dynasty beizi fashion embodies the era’s refined elegance, blending minimalist design with poetic charm. The beizi, a versatile garment, evolved from the Tang dynasty’s banbi into a staple of Song wardrobes, worn by all—from palace consorts to commoners. In this blog, we explore five key aspects of Song dynasty beizi fashion, including its origins, colors, patterns, and aesthetics. Discover why the beizi remains a timeless icon of Chinese style.

Origins of Song Dynasty Beizi Fashion

The beizi, a hallmark of Song dynasty beizi fashion, traces its roots to the Sui and Tang dynasty’s banbi, as noted in Shiwu Jiyuan: “Emperor Gaozu of Tang shortened its sleeves, calling it banbi. This is today’s beizi.” Initially worn by maids, the beizi evolved into a universal garment, favored for its narrow, fitted silhouette and side slits. Unlike the Tang’s bold, flowing robes, the beizi’s straight-collared duijin or slanted-collared jiaoling designs emphasized slenderness, aligning with the Song’s ideal of delicate beauty.

Its lightweight fabric and practical design made it ideal for daily wear, from court to countryside. Learn more about Song dynasty clothing.

Each dynasty boasts its unique cultural charm, with distinct social atmospheres shaping diverse clothing styles. Under the Tang dynasty’s all-embracing cultural splendor, women could don men’s clothing to gallop across fields or defy tradition by “loosely tying silk skirts, half-revealing their chests.” In contrast to the Tang’s open and bold spirit, the Song dynasty was shaped by the ideology of “preserving heavenly principles, suppressing human desires,” leading to an aesthetic where women’s figures were prized for slenderness, and clothing returned to a simple, elegant traditional style.

The beizi, the most emblematic garment of the Song dynasty, evolved from the “banbi” popular in the Sui and Tang dynasties. The Shiwu Jiyuan: Guanmian Shoushi: Banbi records: “Emperor Gaozu of Tang shortened its sleeves, calling it banbi. This is today’s beizi. In the Jianghuai region, it is sometimes called chuozi.” (Beizi is also known as chuozi.)

The Song dynasty placed great emphasis on ethical norms, with clothing reflecting strict hierarchies. Early beizi were worn by low-status maids, but as the garment’s form evolved, these class distinctions faded, and beizi became a common garment worn by everyone—from palace consorts to maids and performers, regardless of status or gender, across court and countryside. The most typical women’s pairing was a moxiong (chest wrap) inside, a baizhe qun (pleated skirt) below, and a narrow-sleeved beizi on top.

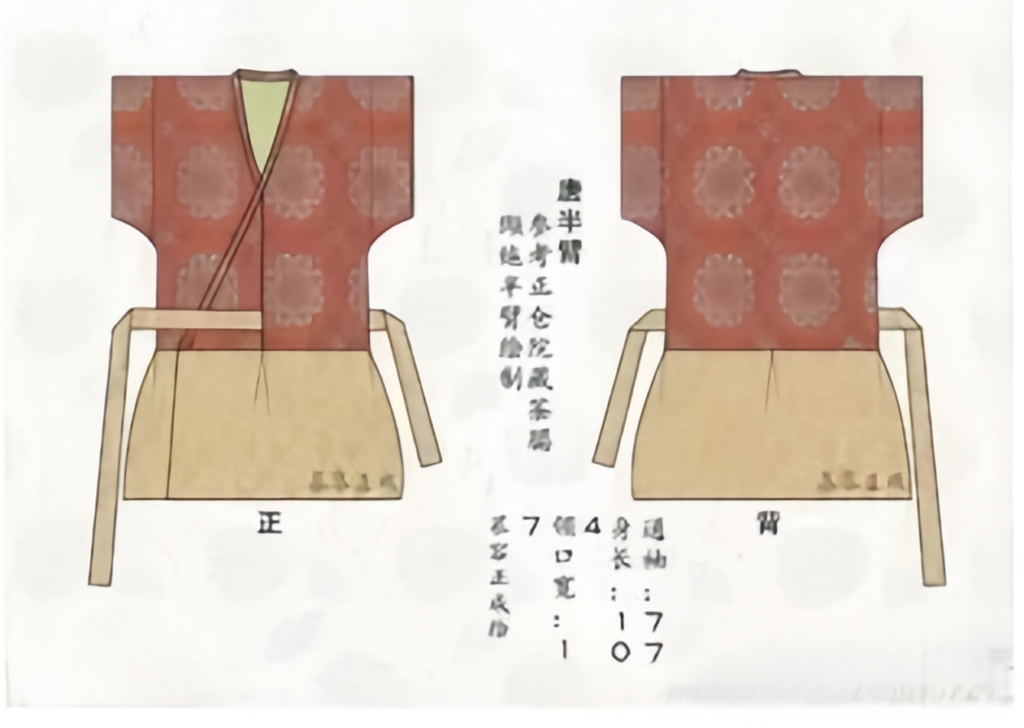

The straight-collared duijin style is a common beizi design, alongside variations like slanted-collared jiaoling and pan-collared jiaoling. Unlike the loose, flowing grandeur of large sleeves, the beizi is narrow and fitted, with a linear silhouette, slits on both sides, and parallel front and back hems left unstitched. When worn, it accentuates a slender, elongated figure, aligning with the Song’s ideal of slim beauty. Moreover, the beizi’s lightweight fabric and unrefined design make it practical for daily activities.

Colors: Muted Elegance in Beizi Design

When Zhao Kuangyin founded the Northern Song, he ascended in a yellow robe. Following Tang traditions, yellow became the emperor’s exclusive color, symbolizing supreme imperial authority, forbidden to commoners and even courtiers. The emperor’s court robes were jiang (crimson), with black-edged collars, sleeves, and hems. The Song dynasty revered Confucian “ritual governance,” establishing a strict official dress code, with color hierarchies in the early Northern Song: jiangzi (crimson-purple) and jiangzhu (crimson-red) were the most prestigious, followed by qing (blue-green) and green.

Commoners’ everyday clothing leaned toward muted, elegant colors like qing, green, blue, and white, while skirts were relatively brighter, yet the color combinations remained harmonious. The traditionalism and conservatism of Neo-Confucianism led to an overall subdued color palette, moving away from the Tang’s bold, high-contrast “clashing colors” like bright red and green. Even when using contrasting colors, the Song opted for restrained, low-saturation shades like pale red and light green for pairings.

Colors like “delicate yellow danwen shan,” “white ru paired with a qing skirt,” or “sky-blue shanzi with an apricot-yellow skirt” catch the eye, exuding refined charm and pursuing a fresh, natural palette.

Patterns: Poetic Motifs in Beizi Fashion

Gongbi flower-and-bird painting reached its peak in the Song dynasty, characterized by meticulous brushwork, precise coloring, and exquisitely detailed outlines. Motifs featuring phoenixes and butterflies (flower-and-bird themes) or plum, orchid, bamboo, and chrysanthemum (floral themes) were beloved by literati and recluses, reflecting noble virtues when woven into clothing patterns. A yanse (smoky-colored) plum-flower embroidered luo single garment with a floral ribbon, unearthed from Huang Sheng’s Southern Song tomb, features a “yinian jing” (year’s scenery) pattern of blooming flowers, vivid and layered with depth.

Zhezhi hua (broken-branch floral) designs, with winding vines and natural motifs, dominated beizi patterns, symbolizing deeper meanings like abundance or virtue. A longjin brocade in the Chengdu Shujin Weaving and Embroidery Museum features gold-threaded lanterns and bees, representing prosperity. These poetic patterns elevate Song dynasty beizi fashion for modern hanfu looks.

The Song dynasty’s realistic, lifelike painting style reflected its aesthetic pursuit of natural, accessible forms with poetic, liberated inner meaning. Beizi patterns primarily featured zhezhi hua (broken-branch floral designs), moving away from the evenly scattered tuanhua (circular floral) layouts. Branches and vines interweave, with flowers adorning the tips, winding as if naturally grown.

In pattern selection, realism emphasized “meaning,” with most designs carrying rich, profound symbolism. A Song dynasty longjin (cage brocade) in the Chengdu Shujin Weaving and Embroidery Museum features a gold-threaded lantern pattern as the main motif, accented with embroidered bees and tassels, symbolizing “feng” (abundance) and “wugu” (five grains), conveying the wish for “abundant harvests.”

The colors and patterns on Song Dynasty clothing are distinctive, with each dynasty showcasing its own vibrant styles. You can explore more about the meanings of colors and patterns in traditional attire.

04 Aesthetics

Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism, the dominant philosophy of the Song dynasty, carried strong feudal undertones, shaping the era’s aesthetic tastes and artistic ideals, which valued simplicity, natural embellishment, and rational beauty. With a policy of prioritizing civil culture over martial prowess, literati held supreme status, their gentlemanly poise—refined as jade, reserved yet ethereal—reflected in their attire. When they composed poetry in the breeze or played chess in bamboo groves, their scholarly elegance inspired widespread emulation.

“Only pure and clean things, not standing out from the crowd,” guided the beizi’s creation under this aesthetic. The Song dynasty rejected extravagance, with clothing trending toward simplicity and conservatism. Decorations were far less opulent than the Tang’s lavish splendor, colors embraced muted elegance, and patterns drew from flower-and-bird paintings. This distinctive Song style left a brilliant mark on China’s 5,000-year clothing history.

Song dynasty beizi fashion is a testament to the era’s cultural and artistic brilliance, blending practicality with poetic elegance. From its versatile origins to its muted beizi color palettes and intricate beizi patterns, the beizi captures the Song’s minimalist charm.

Now that you know about the Song Dynasty Beizi, check out more Chinese traditional clothing. Follow this guide to uncover the charm of other classic Hanfu styles.

Responses