Phoenix Crowns: A Symbol of Nobility – An Introduction to the Phoenix Crown

Ancient Chinese women wore a vast array of jewelry, and hair ornaments were particularly diverse and elaborate, including hairpins, decorative pins, crowns, floral appliqués, and combs, crafted with luxurious materials and intricate designs. Among these, the most iconic were pieces shaped like phoenixes and flowers.

These phoenixes, sculpted in gold, silver, and gemstones, spread their wings gracefully, while flowers such as peonies bloom in full. Placed atop a high bun, they shimmer brilliantly, symbolizing happiness and harmony, creating a unique artistic aesthetic that enhances the wearer’s elegance.

The phoenix, revered as the king of all birds in Chinese culture, represents beauty, nobility, and auspiciousness. It has long symbolized women, naturally becoming a favored motif in female hair ornaments. Over time, the phoenix image combined with flowers, birds, and dragon motifs, decorating crowns and forming the most prestigious female headpiece: the phoenix crown.

To truly understand the phoenix crown, we must trace its origins.

Hairpins and Decorative Pins Featuring Phoenixes Among Flowers

The phoenix combines the most beautiful traits of various birds: a beak like a chicken, jaw like a swallow, wings like a mandarin duck, and a long tail resembling a peacock or pheasant. Xu Shen, in the Han dynasty Shuowen Jiezi, wrote: “The phoenix is a divine bird. Heaven describes it as: ‘Head of a goose, back of a qilin, neck like a snake, tail like a fish, forehead like a stork, beak of a chicken, five colors complete.’”

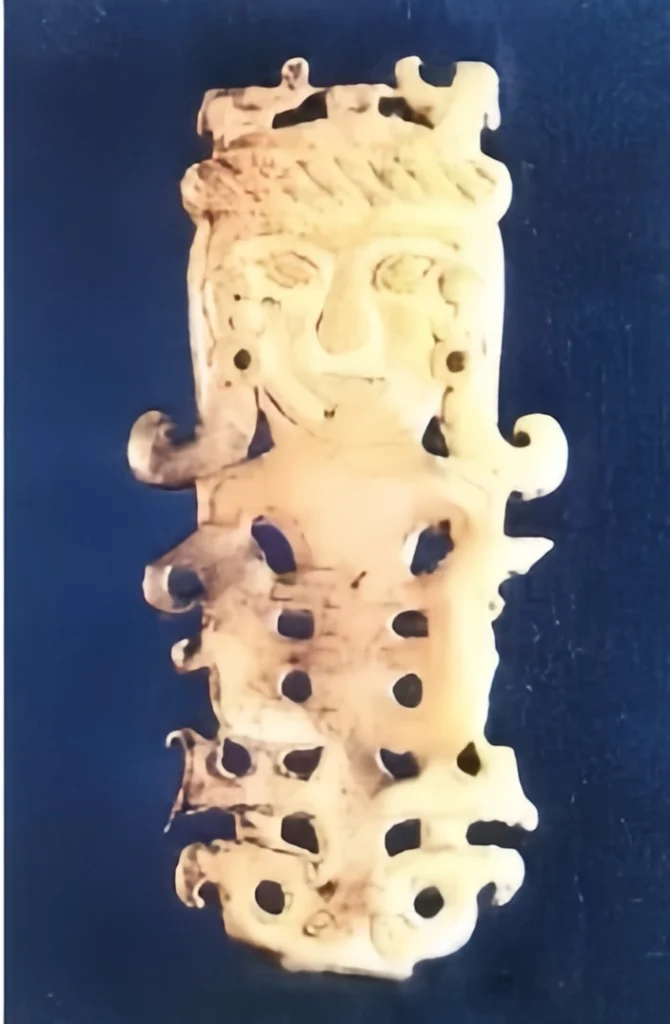

A Neolithic phoenix-shaped pendant unearthed at the Shijiahe cultural site in Hubei depicts a bird with a long tail feather decorated with curved patterns, resembling a peacock’s plumage. This artifact, now in the National Museum of China, resembles a phoenix jade pendant from the tomb of Fu Hao of the Shang dynasty. The original model of the phoenix was likely the peacock that once lived alongside rhinoceroses, elephants, and parrots in the area of the Yin ruins in Henan.

Yuan Ke, in Chinese Mythology, also notes that the phoenix’s prototype is the peacock. Multiple oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty depicting the character for “phoenix” clearly show the long tail feathers, sometimes including the circular eye patterns on the tail.Similar peacock representations were also found at Sanxingdui. Bronze figures of birds, about 7.2 cm tall and 11.6 cm wide, were mounted on sacred bronze trees, featuring crowns and tail feathers with circular holes—an early depiction of the phoenix. In the Han dynasty, bronze tubes from Dingxian, Hebei, show phoenix patterns spread like peacock tails.

Some phoenixes, however, have tails like pheasants, often seen on Zhou dynasty bronzes. Overall, the phoenix originated from the peacock, combining traits from multiple birds. Birds like peacocks and pheasants were regarded as sacred and gradually evolved into the phoenix, representing auspiciousness and peace, as recorded in Shangshu and Shiji.

Thus, ancient women used phoenixes in their hair ornaments not only for beauty but also as symbols of good fortune and female nobility. Over centuries, diverse designs emerged, all recognized as phoenix motifs, satisfying people’s love of beauty and wish for auspiciousness.

Evidence of Phoenix-shaped Hair Ornaments

In the Shang dynasty tomb of Fu Hao, bone hairpins decorated with bird motifs were discovered, reflecting the influence of phoenix imagery. Some bone hairpins feature birds with long beaks, round eyes, and short wings and tails. Similar bone hairpins from the Western Zhou site along the Feng River in Chang’an also show high-crowned phoenixes or chicks as ornamentation.

A jade comb from Fu Hao’s tomb has two facing birds resembling parrots but with crests like phoenixes. The Minneapolis Institute of Art also holds a Shang dynasty jade comb with paired bird engravings. The Palace Museum in Beijing has a Shang jade figurine wearing a round hat, flanked by two small birds on its head, with curled hair resembling tails.

Bronze and ivory hairpins from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods feature phoenixes as well. From the Qin and Han dynasties, textual records confirm phoenix hair ornaments were common. For instance, Ma Gao’s Zhonghua Gujin Zhu·Hairpins traces hairpins back to ancient times, noting that during the Qin dynasty, ivory hairpins were made with phoenix heads, sometimes with gold and silver, forming phoenix hairpins.

During the Jin dynasty, Gu Kaizhi’s Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies shows women wearing golden bird hairpins decorated with kingfisher feathers, resembling these phoenix ornaments. Hou Hanshu details empresses’ ceremonial hair ornaments, including phoenixes adorned with pearls and jade feathers, forming paired hairpins called “Zuo You Yi Heng Zan Zhi.” These ornaments symbolized status and beauty.

Gold “buyao” hairpins, which shake as one moves, were also used, especially in the Han dynasty, with examples unearthed from tombs in Gansu and mentioned in Hanshu. These often feature a bird holding dangling gold leaves amid flowers, producing movement when walking.

Later, the influence of Western regions introduced more elaborate shaking ornaments during the Wei, Jin, and Six Dynasties. Gold phoenix crowns with dangling leaves were found in Inner Mongolia and Jilin, and Gu Kaizhi’s paintings depict paired hairpins with curved branches, bird shapes, and feathers, showing continuity from Han to Wei-Jin traditions.

Phoenix Crowns of the Tang and Five Dynasties

ComAttaching phoenix hairpins (feng chai) and floral appliqués (dian chai) to a crown creates what is known as the Phoenix Crown, or fengguan. According to the Shiyi Ji, such crowns already appeared by the Jin dynasty, during the time of Shi Chong, and quickly became popular among women. Wearing them also marked social prestige and noble status.

Excavated crowns from the Sui dynasty, such as those of Empress Xiao, show that these crowns featured buyao—dangling ornaments that swayed while walking—as well as dian, flowers, and small birds. Restoration illustrations reveal the stunning beauty of these crowns in motion, which aligns well with historical records in the Book of Sui: “False bun, buyao, twelve dian, eight sparrows, nine flowers.” Even the golden hairpins in the Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies are connected to this tradition.

In terms of Tang dynasty crowns, the style can also be called a Phoenix Crown or a buyao crown. Influences from the Sui and earlier Han crowns are clear. However, Tang poetry and literature rarely refer to them explicitly as “Phoenix Crowns.” Only in the Old Book of Tang is there mention of the dance Tianshou Yue created during Empress Wu Zetian’s reign, where performers wore “colorful painted robes and Phoenix Crowns,” showing that the name existed early on but was not widely used.

Here, we highlight images of Tang and Five Dynasties crowns.

During the Tang and Five Dynasties, Phoenix Crowns generally took two forms.

One form is seen in Wu Daozi’s Fomu Sendzi Tianwang Tu, depicting the Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, wearing a crown with a single phoenix, complemented by side ornaments (bo bin), floral hairpins, and dian chai. The phoenix spreads its wings atop a floral base, standing out as the central decoration.

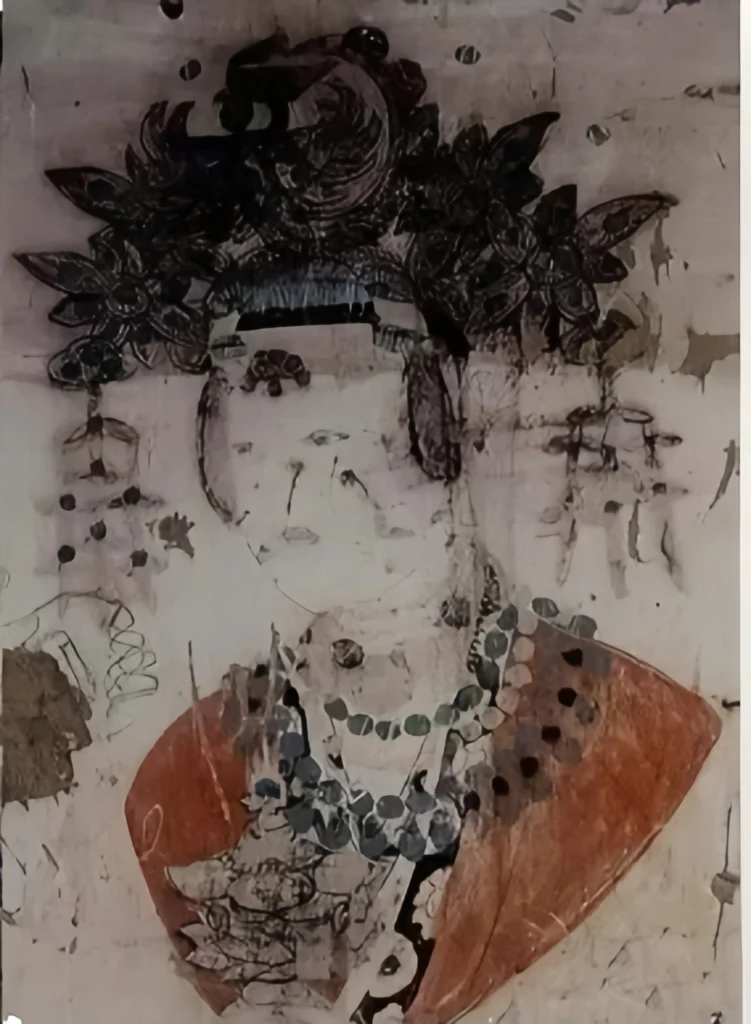

Similar crowns appear in Dunhuang art. In a silk painting of Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva (now in the Freer Gallery of Art, USA), female attendants wearing wide-sleeved robes hold incense burners. The caption notes: “Princess Li of the Kingdom of Jincheng in Great Yutian offers tribute.” Scholars believe this represents a princess from the Yutian royal family married into the ruling Cao family of Dunhuang. She wears a golden crown with a large phoenix perched on a floral base, wings spread and tail curled, decorated with turquoise. Small hairpins and dangling floral tassels enhance the crown’s elegance.

In Dunhuang Cave 61 murals, female attendants wear very similar phoenix crowns: a phoenix on a flower pedestal, side hairpins, dangling tassels, and turquoise inlays, paired with wide-sleeved ceremonial robes and flowing silk scarves.

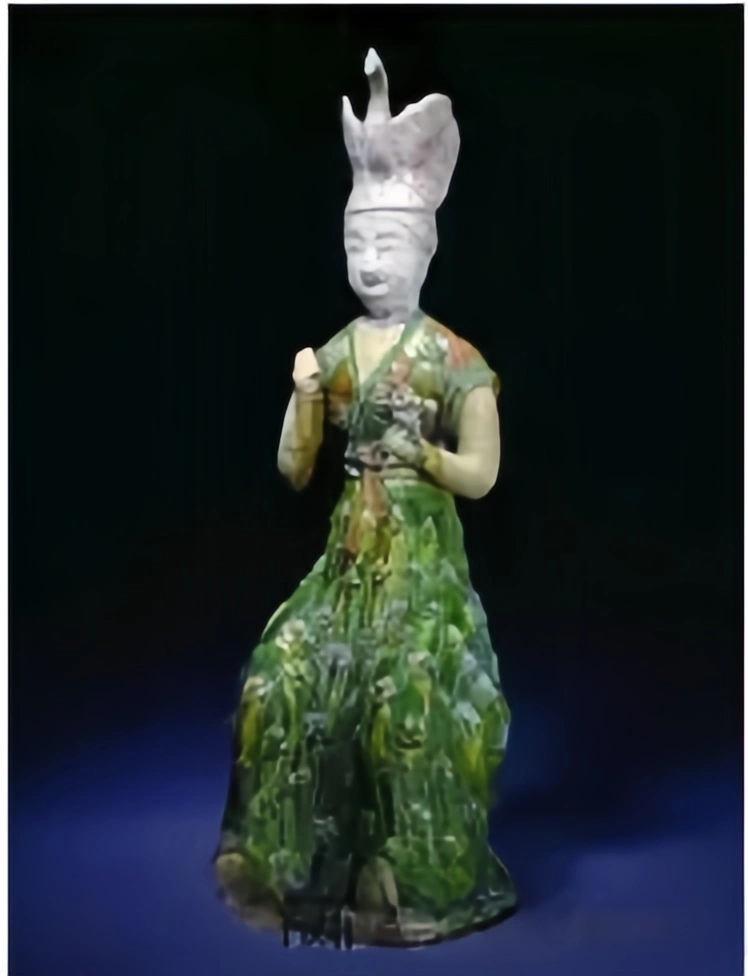

A Tang dynasty ceramic female figurine in the Palace Museum, Beijing, also wears a high crown with a phoenix spreading its wings. Though the phoenix is simpler and lacks painted colors or swaying ornaments, it is still considered a Phoenix Crown.

This single-large-phoenix style evolved from the first form of large Phoenix Hairpins seen in the tombs of Li Xian and Xue Jing’s attendants. Dunhuang murals show many similar examples: women wearing crowns with a single large phoenix, green turquoise inlays, floral hairpins, and ceremonial robes with flowing silk scarves.

The second form of Phoenix Crown is seen in the stone coffin line drawings of female attendants in the tomb of Prince Yide, Li Chongrun (Tang dynasty). These women, likely palace attendants, wear crowns inlaid with pearls, floral dian, and smaller phoenix hairpins, with dangling jade and beads (buyao).

Poet Wang Jian’s Palace Poems describes:

“Jade cicadas and golden sparrows inserted in layers, green hair piled high; at the dance, spring winds drop ornaments, at the return, a comb is given.”

Various small birds, insects, and butterfly-shaped dian and hairpins, along with precious combs, decorated the crown. Excavated Phoenix Crowns from Li Jue’s tomb, a descendant of Tang Gaozu, feature gold crown frames with layered floral leaves, phoenix tail feathers, square fangsheng patterns, and mandarin duck motifs, inlaid with turquoise, amber, pearls, shell inlays, jade flowers, rubies, agate, and gold granules. Some gold pieces are paired with kingfisher feathers, confirming textual records of using kingfisher or turquoise feathers.

The most eye-catching part is the phoenix tail feather motif at the front, outlined in gold, layered, and dotted with small turquoise beads to mimic natural peacock tail “eyes.” Two gold phoenix hairpins flank the crown, also inlaid with turquoise and beads. Dangling pearls and beads maintain the distinctive buyao effect.

Tang and Five Dynasties Phoenix Crowns were generally like this. Together with sparrow hairpins seen in the Yanfei tomb murals, they preserved the essence of buyao crowns and can be directly called Phoenix Crowns. Bai Juyi’s poetry, describing “rainbow robes and flowing scarves with buyao crowns, layered with dian and beads,” closely matches these crowns: vivid, sparkling, and luxurious.

“Before the table, dancers with faces like jade, not wearing worldly clothes; rainbow robes and flowing scarves with buyao crowns, adorned with dian and beads.”

Here, the flowing scarves (xiapei) refer to long, decorative silk strips worn over the shoulders, first recorded in Sui-Tang times, which enhance the visual elegance. Dunhuang murals depict similar scenes. Even the famous Yang Guifei performed the Feathered Robe and Rainbow Skirt Dance before Emperor Xuanzong wearing such attire, with buyao swaying and scarves floating—a dazzling spectacle.

Phoenix Crowns in the Song Dynasty

In operas and film dramas we often see brides from official or wealthy families wearing a phoenix crown on their heads and draped with two xiapei (long cloud-scarves). The costume looks extremely gorgeous, representing the wearer’s noble status and containing many historical clues and bygone stories awaiting our interpretation.

Evolution from Tang to Song

The form of the phoenix crown with xiapei traces back to remote prehistoric times, developed through the Tang and Five Dynasties, and was fixed into a standard form in the Song and Ming dynasties.

As already mentioned, the phoenix crown in the Tang and Five Dynasties was well developed and was used together with xiapei (draped scarves) and ritual clothing — this can be seen in Dunhuang murals. The Tang/Five Dynasties phoenix crowns directly influenced Song crowns. Song crowns included bead-and-kingfisher-feather round crowns (zhucui tuanguan); for example, the half-body portrait of Empress Xuanzu shows a phoenix crown worn with wide sleeves. The crown type developed further into crowns matched with zhiyi (feathered ceremonial robes), in effect combining dragon and phoenix into a dragon-phoenix crown — formally called the long-feng hua-chai guan (dragon-phoenix flower-pin crown).

Formal Dress: Phoenix Crown + Xiapei + Wide Sleeves

By the Song, the phoenix crown and xiapei became an established combination and functioned as a rank symbol for empresses and noblewomen. Zhao Feng has done research on the dashan (wide-sleeved robe) and xiapei.

Phoenix crown + xiapei + wide sleeves, for Song empresses and consorts, was a common formal dress second only to the phoenix crown with zhiyi. The Song History — Treatise on Attire records: “For regular dress, the empress and consorts wear wide sleeves, colored collars, long skirts, xiapei, and jade pendants.”

The empress’s and consorts’ regular dress, while subordinate to the zhiyi, was still a ritual garment used when the utmost formality was not required; its formal name was daxiu — a large-sleeved ceremonial robe also called dayi or guangxiu, worn by empresses, princesses, and wealthy women. The seated portrait of Empress Dowager Du (mother of Emperor Xuanzu) shows this kind of wide sleeve: pale yellow, very long, straight collar, very wide sleeves, paired with a long skirt and xiapei.

The xiapei has a blue ground with cloud and phoenix patterns; it rests on the shoulders and hangs down, ending with a jade pendant. Her crown is a round tuanguan, inlaid with kingfisher blue feathers and pearls, decorated with a phoenix motif in front and with pearl-dangling side ornaments (bobo).

Archaeological Evidence: Huang Sheng Tomb

In the Southern Song, the Huang Sheng tomb in Fuzhou also yielded a wide-sleeved robe plus a straight hanging sash similar to a xiapei; this constituted Huang Sheng’s highest ritual dress. Since Huang Sheng was a young woman from an ordinary official household, she could not wear zhiyi and did not need a full xiapei; Zhu Xi’s Family Rituals states: “Wide sleeves — now women’s short jackets are wide; their length reaches the knee, sleeves one foot two cun long.” The Menglianglu records “gold-washed wide sleeves, yellow gauze.” The robe was made of crimson-yellow gauze with lining, front overlap, wide sleeves, and a triangular pouch sewn on the back to hold the straight sash.

Two long narrow sashes were also found in Huang Sheng’s tomb, both plain gauze ground; one measured 213 cm and the other 195 cm, both 6.2 cm wide, fully embroidered with more than ten types of seasonal winding-branch floral patterns in many colors. Each sash is in two pieces stitched with silk thread, with triangular cut ends; one was found hanging across the chest in a V-shape, its front end attached to a round gold pendant bearing a double-phoenix and lotus motif.

Scholar Gao Chunming judged these two pieces to be straight xiapei used with wide sleeves; the wearing method matches the Empress Dowager Du portrait — the front end hanging down in front and the rear end placed into the triangular pouch on the back (see The Southern Song Huang Sheng Tomb in Fuzhou). But no head crown was found in Huang Sheng’s tomb — several gilded silver hairpins were discovered that were directly inserted into her hair bun.

Song tombs from Fuzhou (Chayuan Village) and the Zhou family tomb in De’an, Jiangxi, also yielded similar wide-sleeved robes with a triangular pocket on the back. They also had straight xiapei and pendants. The Zhou lady’s hair was formed into a bun and adorned with a special gold-wired bun piece, into which gold hairpins were inserted; one gold pin carried a net of pearls containing a sachet, resembling a buyao. These finds reflect part of the ritual system of that period.

Imperial Zhiyi & Dragon-Phoenix Crown

As for the highest ritual dress for Song empresses, it was the zhiyi paired with a dragon-phoenix flower-pin crown — more magnificent than the round coronets — used for the most solemn ceremonies: investitures, court audiences, and major rites. The Song History records this.

Song History — Treatise on Attire notes that the empress and consorts were to wear yiyi (also called zhiyi) decorated with pheasant (zhai) motifs; the empress’s crown had twelve large flower branches and the same number of smaller flowers, totaling twenty-four floral trees (other noblewomen had progressively fewer flower trees; the crown for the crown prince’s wife had eighteen branches). Both sides of the crown had bobo side ornaments. The crown’s decoration included “nine dragons and four phoenixes.” The text does not exhaustively describe the crown pattern, but Jin dynasty records — influenced by Song — describe the empress’s “flower-branch crown” with more details: Shengzi bases, nine dragons and four phoenixes, etc., which help supplement the Song descriptions (see Sun Ji’s study).

Crown Structure & Kingfisher Craftsmanship

The crown body — called the shengzi — was wrapped externally in blue gauze and lined with blue silk and gold-red gauze. The exterior was then set with tiny pearls, spread with kingfisher feathers, and finished using gilding and powdering techniques (the so-called “pavement-kingfisher peony,” “pavement-feather peony,” and “feather-leaf pearl flowers” methods). Pearl and kingfisher inlay, gilding, painting, and small gold beads were all indispensable.

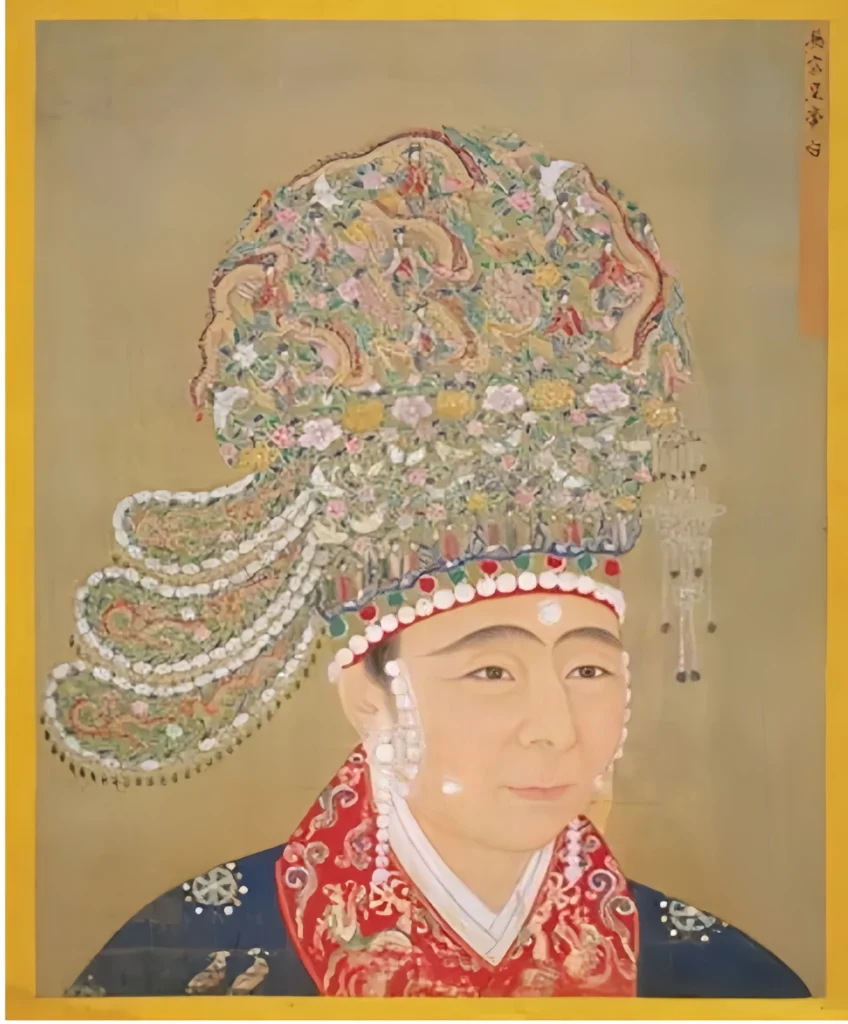

Craftsmen produced nine cloud-dragons and four phoenixes; at the front a large dragon held a tasseled ball; there were twelve front and back large flowers and many birds — kingfishers, peacocks, cloud cranes and other birds — plus a register of Queen Mother’s attendant immortals (the later Ming noble headpieces that depict Queen Mother and immortals derive from this), floating petals, and more. The crown’s rear had a naiyan (an attaching ornament), with two bobo panels on each side decorated with golden cicada motifs; the crown rim had seven decorative dianhua in front and two at the back. There was also a red gauze ribbon embroidered with gold. In short, it shone with pearls, gold, and kingfisher colors.

Portraits of multiple Song empresses show such crowns with similar basic forms though differing details — the motifs of dragons, phoenixes, flowers, and immortals are common, set with pearls and kingfisher inlay. For example, Empress Liu (wife of Emperor Zhenzong) wears a crown with a major dragon motif in front, dragons and phoenixes (sometimes human-faced bird figures), rows of immortals among flowers, and three side bobo panels on each side — dazzling to behold.

The empress of Emperor Huizong’s portrait wears a crown with three bobo on each side, the crown ornamented overall with human-face bird feitian figures (or jialingpinjia?), large pearl flowers, and a big inlaid green-feathered dragon in front; from the dragon’s mouth hang long tasselled balls and bead droplets, and the crown rim is painted with rows of immortal figures. The overall emphasis is on pearl brilliance.

Empress of Emperor Qinzong’s crown follows a similar type: gold and kingfisher dragons and phoenixes in flight, inlaid with pearls, filled with red-yellow-pink flowers and green leaves, lined with rows of immortals, and bobo showing roaming dragon patterns.

Empress Gao (wife of Emperor Yingzong) had an especially sumptuous crown: painted bands of immortal figures at the rim, several red-fin gold dragons coiling and weaving, flowering clusters of different sizes with feitian, cloud cranes, mandarin ducks, etc., closer to the description recorded in the Jin History.

Southern Song and later portraits similarly show dragons in motion, flying phoenixes, and immortals, while Empress Cao (wife of Renzong) wears a crown that features only cloud and dragon motifs.

These portrait crowns, while not identical to the textual descriptions, align in many respects — overall the dragon motif dominates and phoenixes are less visible. Some crowns depict bird-bodied human-faced feitian that may serve as phoenix imagery. Of course Song Shen-zong’s empress portraits and Emperor Gao’s empress portrait do show phoenixes on the crowns.

Yuan Legacy: From Song to Ming Kingfisher Tradition

Some prosperous families in the Song also put phoenix crowns on singers and dancers. For example, Shi Hao’s Zhezhi Ge Tou describes a zhezhi dancing girl wearing a phoenix crown, a slim waist bound with plain sash, and a body covered in embroidered brocade meant for performance. Daoist female deities were also influenced by real life and depicted wearing phoenix crowns. The goddess of Jinci’s Shengmu Hall is shown with a phoenix crown featuring cloud motifs, phoenixes, and flower branches.

In Yuan times, the famous Yongle Palace murals in Shanxi depict the Queen Mother of the West seated in majesty wearing a gilded dragon-phoenix crown with bobo, similar to real crowns of Song/Jin style; the only special mark is a “Kun” trigram indicating her identity. Daoist deities such as Bixia Yuanjun and Mazu are also often shown wearing phoenix crowns.

Yuan drama and literature likewise mention phoenix crowns and xiapei. Yang Xianzhi’s Xiaoxiang Rain (act 4) includes the line: “Take off this gilded-flower eight-treasure phoenix crown, take off this cloud-mist five-color xiapei,” indicating their popularity.

Archaeological finds from the Yuan, such as the tomb items of Cao (mother of Zhang Shicheng), include geometric patterned brocades and dragon-phoenix ribbons that correspond to xiapei. The crown in her tomb was constructed with a bamboo frame, covered with hemp and yellow thin gauze, overlaid with kingfisher blue feathers, fastened by nine gold wire hoops; the crown rim is set with peach-shaped gilt jade pieces.

This round-crown for xiapei use connects by lineage to earlier jinjue chai, the Tang Li Jue tomb phoenix crown, and Song-period crowns; in particular, the pucui (kingfisher inlay) technique goes back to the bird-pin and peacock feather decorations, then to Li Jue’s crown, then to Song empress headwear, and later Ming crowns’ diancui (dotting with kingfisher) — an unbroken tradition.

Phoenix Crowns in the Ming Dynasty

In the Ming dynasty, phoenix crowns were used together with xiapei and zhiyi; Zhou Xibao studied this in History of Ancient Chinese Costume. The crown craft and forms developed on earlier bases, with added embellishment. According to Ming texts (Ming History, Ming Huidian, Sancai Tuhui, Zhongdong Gongguanfu), Ming phoenix crowns largely followed Song forms, but actual Ming examples show variations.

Ming texts provide detailed descriptions. Surviving crowns from the Dingling tombs of the Wanli Emperor’s two empresses reflect this. From these materials the Ming phoenix crown appears to continue Song patterns but with many detail differences.

The Ming records say the empress’s coronation/temple crowns (huiyi/zhiyi) should follow certain rules: under Hongwu it was a round frame decorated with nine dragons and four phoenixes, twelve flower trees, two bobo side pieces, and twelve dianhua; Yongle (third year) changed to nine emerald dragons and four gold phoenixes, with one dragon holding a large bead and many bead droplets, pearl/kingfisher clouds forty pieces, twelve jewel flowers, twelve kingfisher inlay dian, and three side bobo each side, decorated with gold dragon and kingfisher cloud, with bead droplets, etc. The textual descriptions show Song influence.

Dingling Tombs: Twelve & Nine Dragon-Phoenix Crowns

These Ming-era coronets were represented in Sancai Tuhui. Actual examples were found in Wanli’s Dingling: one is the Twelve Dragons & Nine Phoenixes crown (for Empress Xiaoduan) and the Nine Dragons & Nine Phoenixes crown (for Empress Xiaojing) — the counts differ slightly from the records.

The Twelve-Dragon/Nine-Phoenix crown was built on a bamboo wire frame, lined and covered with silk, inlaid with kingfisher cuiyun and cuye, gold filigree pearl flowers with gem centers, surrounded by strings of pearls. Gold filigree dragons were made, flying phoenixes inlaid with kingfisher and set with small rubies for eyes, distributed over the crown top and front/back; each phoenix or dragon holds gem bead droplets. The crown rim was a gold band decorated with gem and pearl flowers. Each side had three metal-wire-woven shaped bobo decorated with gold dragon and pearl flowers, with dangling pearl droplets. When worn, the bobo and bead droplets sway with movement, increasing the crown’s splendor.

The Nine-Dragon/Eight-Phoenix crowns had a mid layer with a ring of kingfisher phoenixes and another phoenix at the back; above them nine flying dragons, all holding bead droplets. Each side had three bobo panels with gold dragons and jeweled flowers and dangling beads.

The empress’s everyday formal wear in Ming ritual texts is called yanju guanfu. The Ming History — Treatise on Attire records that in Hongwu year three the empress wore the double-phoenix lifting-dragon crown with multicolored round robe; Hongwu year four prescribed dragon-phoenix pearl-kingfisher crowns; the crown may be made as a teji (special bun) topped with dragon-phoenix. It was paired with wide-sleeved gowns and xiapei. Ming portraits such as that of Empress Xu wear a double-phoenix lifting-dragon crown with two phoenixes on the sides and a dragon in the center, with hanging bead plaques from the dragon’s mouth; the robe is yellow wide-sleeved with a red-base dragon xiapei. The pattern echoes Song wide-sleeved ritual dress.

One of Wanli’s empress portraits shows the empress wearing the same type of crown but paired with a circular robe and without xiapei.

There are many empress portraits wearing three-dragon crowns, e.g., Empress Xiaozhuang (wife of Emperor Yingzong) portrait. The Dingling excavations found Empress Xiaoduan’s Six-Dragon-Three-Phoenix crown and Empress Xiaojing’s Three-Dragon-Two-Phoenix crown, both with hanging bead plaques. The Six-Dragon-Three-Phoenix crown has one dragon in the center holding a bead droplet facing forward, side dragons facing outward holding long bead plaques; three phoenixes occupy the middle tier with bead droplets, one frontal and two lateral; the crown rear has three flying dragons. Lower tiers are decorated with pearl flowers, kingfisher clouds, kingfisher leaves, and each side has three bobo panels with gold dragons and pearl flowers with dangling beads. The Three-Dragon-Two-Phoenix crown is similar — Empress Xiaojing’s crown.

Speaking of Empress Xiaojing: the dragon/phoenix counts on her crowns were fewer than Empress Xiaoduan’s, possibly connected to her unfortunate life. Although titled empress, she was posthumously elevated: originally a palace maid who bore Wanli’s eldest son (the later Emperor Guangzong), she was neglected in favor of another consort and sent to the cold palace. Objects from her tomb are worn and poor; her crowns and fine garments were placed in the Dingling by her son after he became emperor as a form of restitution — she likely never wore them in life.

In Yongle year three, the empress’s regular dress was standardized as the black gauze (zaodu) crown with a front emerald boshan ornament, one gold dragon and two kingfisher phoenixes holding bead droplets, plus jewel peony, kingfisher leaves, flower bobo, pearl-kingfisher clouds, and three bobo panels each side decorated with luan and phoenix motifs.

Empress portraits of Emperor Chengzu’s Empress Xu show this crown: slightly revealing the black gauze at the top, with an undulating arch line. Similar to the crown found in Zhang Shicheng’s mother’s tomb. The crown is decorated with dragon/phoenix and jeweled flowers with hanging bead plaques, paired with a yellow wide robe and dark red xiapei — closer to the Song pearl-kingfisher round crown paired with wide sleeves.

Thus, the empress had at least three crown types: the round-hat style phoenix crown, the special-bun double-phoenix lifting-dragon crown (aka dragon-phoenix jeweled crown), and the smaller black-gauze crown; the latter two share similar decorations, and the black gauze crown later merged into the dragon-phoenix jeweled crown.

Ming Huidian records that the double-phoenix lifting-dragon crown could also be made of black gauze, but in empress portraits the entire crown appears covered with kingfisher inlay and jeweled flowers, making the black gauze invisible.

Rank Hierarchy & Folk Adoption

Although forms differ, all three types can be generically called phoenix crowns.The Dingling tomb also yielded two empresses’ pearl-inlaid kingfisher xiapei covered with pearls and the four phoenix crowns, but no wide-sleeved robes or zhiyi were found; only short jackets and skirts were recovered.

Therefore we must consult Ming-period portraits to see the matching of phoenix crowns, xiapei, and ritual robes.The dragon-phoenix jeweled crown is mainly paired with the wide-sleeved robe and xiapei. The portrait of Empress Xiaokangjing is the standard type; her xiapei is deep green, differing from the red xiapei in other empress portraits. The xiapei excavated at Dingling also differs in manufacture from the method recorded in Ming Huidian. Empress zhiyi could also be paired with xiapei, such as in portraits of Empress Li, contrary to technical descriptions.

These divergences show that ritual codes and actual practice differ in detail.The crowns and costumes for the crown-princesses and princes’ wives ranked below the empress’s crown. Imperial consorts could use only phoenix motifs but not dragons. Wives of princes used nine-pheasant (jiudie) crowns and wives of commandery princes used seven-pheasant (qidie) crowns; they could not use phoenix motifs with dragons — a regulation consistent with the Song History. Zhiyi remained the ritual robe; the everyday dress was the luan-feng (phoenix) crown with gold-embroidered multicolor round robe.

In practice, however, regulations were not strictly followed. For example, in the tomb of Ningjing’s wife Wu from Nanchang (Ming), a phoenix crown was unearthed decorated with gold dianhua, gold phoenix motifs, phoenix hairpins, many small pearls — still phoenix imagery used widely. The tomb also included wide sleeves and xiapei. Her xiapei was in two pieces and when worn the xiapei was placed into the triangular back pouch of the wide robe.

Ming ritual dress for official wives (mingfu) used a special bun crown shaped like a triangle, which could not include dragons or phoenixes but employed pearls, gold and silver for feathered decor, peacock motifs, jeweled peonies, leaves, dianhua, kingfisher clouds, gold dian, hanging bead droplets, combs, and hairpins. The number of ornaments decreased with the husband’s rank: the highest grade used the shansong teji and so on. Everyday wear included jeweled qingyun crowns.The Sancai Tuhui shows images of such wives’ crown-attire: hairpins, crowns (commonly called phoenix crowns), earrings (actually ear pendants in the illustrations), and buns (various types).

In practice phoenix imagery was abundant because strict rank rules were unpopular. Phoenix motifs, unlike dragons, were less strictly regulated and therefore widely used among women, including the common folk.

In Nanjing, the tomb of Wei’s wife Zhu (a lady of the Wei family) yielded a crown decorated with lingzhi leaves, ruyi motifs, many pearls, a pair of gold phoenix hairpins and phoenix hairpins holding pearl plaques — close to a double-phoenix lifting-dragon crown.

Late-Ming novels also record such dress. For example, Chapter 85 of Awakened to Marriage describes a high-ranking official’s wife wearing a qilin-robe with silver belt and gauze skirt, “a head full of pearls and jewels, large white round pearl bead plaques, a gilded phoenix holding a string of pearls.” Similarly, portraits of various lineages show ladies wearing crowns with central jeweled peony surrounded by pearl-feather zhai and side gold phoenix hairpins holding bead plaques.

In the secluded courtyards, these wives presented many faces — stern, friendly, aged — and behind the same ceremonial dress perhaps many untold stories lie.By the Qing, xiapei had widened and sometimes had tassels, used like a vest, paired with phoenix crowns.

Many Ming and Qing noblewomen’s crowns that can be generically called phoenix crowns survive today. Examples include: a Ming gold phoenix crown from Yang family Tusi tombs (Guizhou Museum) with a silver sheet base inlaid with dragons, phoenixes and peonies; a Ming gold-inlaid gemmed flower-butterfly-phoenix crown from Liu Niangjing tomb (Qichun, Hubei, Hubei Museum); gilded silver phoenix crowns in Zhenjiang Museum; silver phoenix crowns in Wuhan Museum.

The Nanjing Museum has a Qing-period golden phoenix crown worn by the wife of the Jiangnan Governor Li Wei on the occasion of receiving a bestowal; the crown frame shows mountain-cliff and sea-wave patterns, decorated with gilt-metal dragons and phoenixes and inlaid with pink tourmaline and many rubies. Another Qing crown from Bi Yuan’s wife (governor of Shaanxi-Gansu and Huguang) features a double-dragon playing-pearl pattern at the crown base, filled with gilt phoenixes, flowers, clouds and inscription plates with characters such as “En-Glory,” “Sun-Moon,” “Bestowed,” “Imperial Warrant,” “Court Crown.” These golden jeweled phoenix crowns visually embody former women’s honor.

Qing Legacy & Modern Weddings

Qing empresses also wore phoenix crowns; their crown tops were sometimes pagoda-shaped, studded with gold filigree phoenixes and jewels.

Common women could rent phoenix crowns for weddings — usually made of pearls and gold — and wear them for the ceremony.

The auspicious phoenix among the floral regalia on Chinese women’s heads, paired with dragons, represents yin-yang harmony and noble prestige — exuding magnificent and beautiful splendor. Together with xiapei and ceremonial robes it became a symbol of dignified grandeur. For most women, the phoenix crown and xiapei were at least worn once in life, making them an emblem of honor.

Its rich cultural meaning deserves inheritance; arguably it should be nominated as a world-class intangible cultural heritage.

Today phoenix crowns remain popular in traditional weddings — many brides choose crowns made of imitation pearls and wear them for photos. On the opera stage, crowns made with rhinestones and simulated kingfisher inlay are used. As a cultural form it remains beloved and will continue.

Responses