Veiled Charm: The Allure of the Weimao

Have you ever dreamed of wearing a flowing, ethereal Ruqun, topped with a gauzy Wei-mao? With a sword in hand and a horse by your side, roaming the world like a heroine from a novel.

In ancient China, the Wei-mao (veiled hat) was an essential accessory. The most iconic scene? In historical dramas, when the heroine first appears, a breeze lifts the veil to reveal a breathtaking face, stealing the hero’s heart—and the audience’s too.

Origins of the Weimao

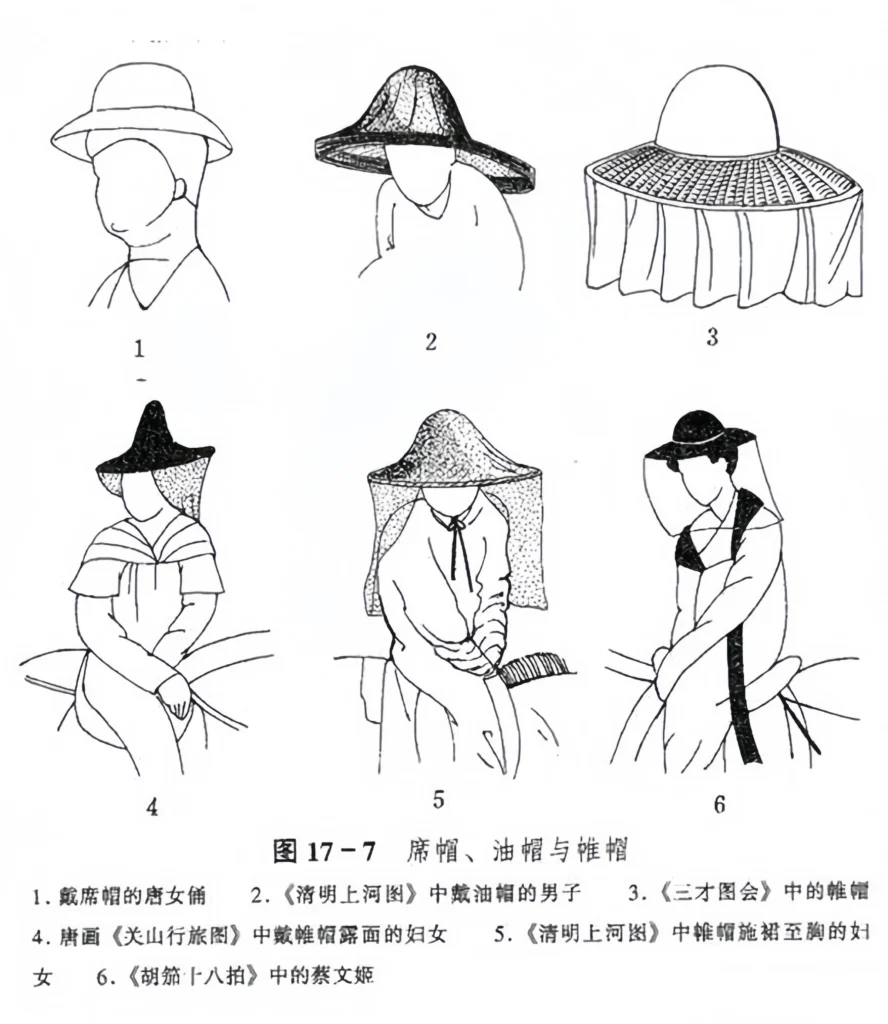

The Wei-mao began as a decorative accessory in Hu (non-Han) fashion, originally called Mili (full veil). Made of black gauze, it had a wide brim with dangling silk netting or thin muslin reaching the neck, used to conceal the face. By the Sui and Tang Dynasties, the netting was shortened, earning the name “shallow veil” (qianlu).

The Mili was a full-body shield of sheer gauze attached to the hat’s brim, while the Wei-mao had a net or silk strings hanging around the edges, reaching the neck. Used by both men and women, women’s Wei-mao often sparkled with pearls or jade.

“The Wei-mao, like today’s wide-brimmed hat, has a net hanging around it.”

— Song Dynasty, Guo Ruoxu, Records of Paintings

This “surrounding net” was far sheerer than gauze or silk, barely hiding the wearer’s figure or face. In the early Tang, officials tried banning it—likely because it was too revealing. Adorned with pearls, jewels, or kingfisher feathers shaped into flowers, the Wei-mao was stunningly ornate. No wonder Tang women clung to it despite bans: “Though briefly paused, it soon returned.”

In murals, a maidservant holds a Wei-mao, ready to present it to her mistress, showing devotion and readiness for travel. Yan Yonghe, no ordinary woman, was a concubine of Emperor Taizong at thirteen, mother to princes, and later named Duchess of Yue. Her tomb, a resting place of nobility, features this Wei-mao for horseback outings, capturing the bold spirit of the early Tang.

Yan Yonghe was laid to rest in 671 CE, in a tomb near Zhaoling Mausoleum. That same year, Emperor Gaozong, alarmed by the Wei-mao’s popularity, issued a second edict to curb this “improper trend.” His decree noted: “Recently, many wear Wei-mao, abandoning the Mili,” marking a shift from Mili to Wei-mao. Thus, Yan likely used the longer Mili in her early years, embracing the Wei-mao as a new fashion in her final two decades.

Historical Roots

The Book of Jin, Records of Foreign Tribes notes: “Men wear long skirts and hats, or don theMili.” This is the earliest mention of the Wei-mao’s precursor.

Initially, men wore wind-blocking hats or Mili to shield against sand. Later, women adopted it to veil their faces during outings, preventing strangers’ gazes.

The Book of Sui, Biography of Prince Yang Jun records: “Jun was clever… crafting a jeweled Mili for his consort.”

Yang Jun, third son of Sui’s Emperor Wen, made a Mili adorned with precious gems for his wife, showcasing its luxury.

The Wei-mao peaked in the Tang Dynasty.

The New Tang Book, Treatise on Clothing records: “Early on, women used body-length Mili. From Yonghui, they wore Wei-mao to the neck. By Empress Wu’s time, Wei-mao dominated, and Mili vanished. In Kaiyuan, palace women rode with Hu hats, faces unveiled, with no cover. Commoners followed… soon, Wei-mao faded.”

In early Tang, Mili covered the body. By Yonghui (650–655 CE), Wei-mao reached only the neck. By Empress Wu’s era, Wei-mao reigned, but by Kaiyuan (713–741 CE), open styles like Hu hats left faces bare, and Wei-mao waned.

Even famed painter Yan Liben erred under Tang influence, depicting a Weimao in his Zhaozhao Leaving the Frontier, despite its absence in Han times. His iconic work led to the Weimao being misnamed “Zhaojun hat,” a term still used today.

Legacy Beyond Tang

Though Tang women later skipped Weimao for daily wear, it didn’t vanish. In the Song Dynasty, women used full-body purple silk covers, called “veils” (gaitou), echoing Mili and Weimao.

Early Chinese historical dramas paid close attention to Weimao’s design.

“Once a palace beauty, she danced like a fleeting swan, as if spring soared over Dongting Lake. Her steps steady in Liangzhou’s tune, a fresh bloom in the breeze.”

Chen Hong’s Diaochan in Romance of the Three Kingdoms embodied the allure of the Four Beauties.

Paintings like Emperor Ming’s Flight to Shu and Tang tomb figurines from Astana show horse-riding women in Weimao.

The Song inherited Tang customs, including women wearing Weimao for outings.

In Zhang Zeduan’s Along the River During Qingming, though few women appear, their Weimao-inspired veils hint at this lingering style.

The Weimao’s Legacy Beyond the Tang Dynasty

Though Tang Dynasty women later skipped Weimao for daily wear, it persisted. In the Song Dynasty, women used full-body purple silk covers, called “veils” (gaitou), echoing Mili and Weimao. Early Chinese historical dramas meticulously designed Weimao, as seen in Chen Hong’s Diaochan in Romance of the Three Kingdoms, embodying the allure of the Four Beauties.

Paintings like Emperor Ming’s Flight to Shu and Tang tomb figurines from Astana, viewable at The State Hermitage Museum, show horse-riding women in Weimao. In Zhang Zeduan’s Along the River During Qingming, Weimao-inspired veils hint at this lingering style in Chinese historical fashion.

Responses