Rediscovering the Waist-High Ruqun of Late Ming Women

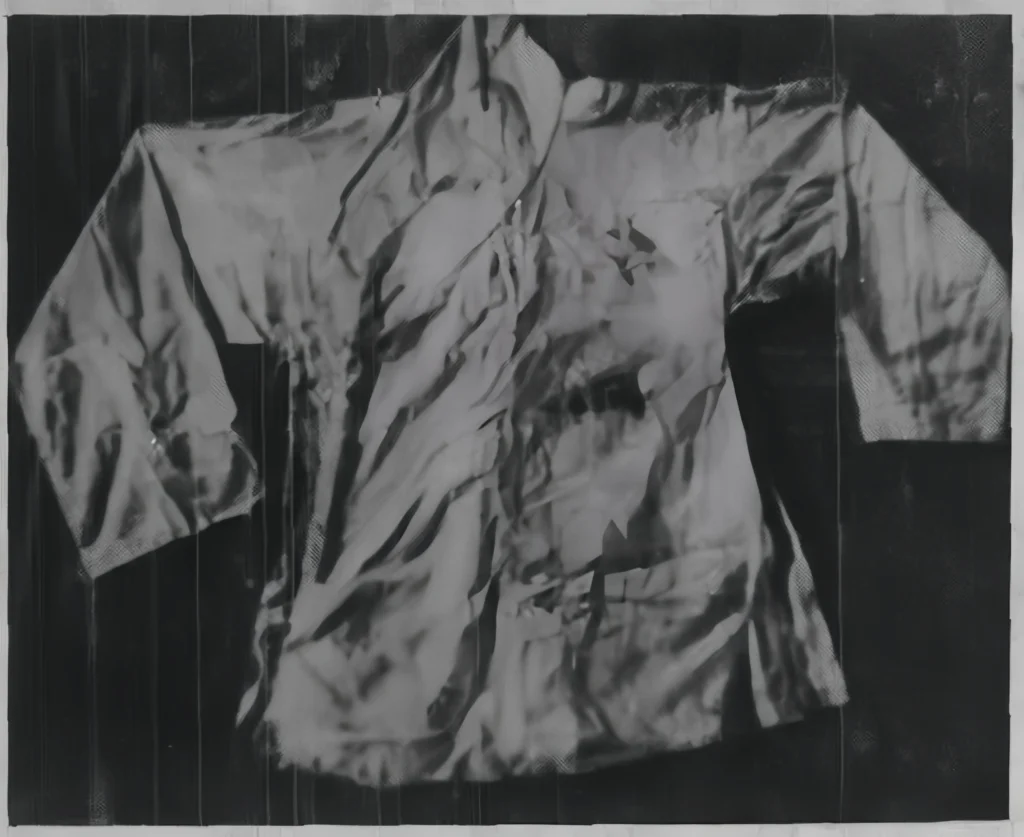

The waist-high ruqun, a hallmark of late Ming fashion, redefined Chinese Hanfu clothing with its vibrant skirt-over-top style. Unlike traditional top-over-skirt designs, late Ming women tied a traditional wrap skirt over long robes, blending practicality and elegance. This distinctive approach, documented in historical artifacts, showcased the diversity of late Ming fashion.

Abstract:

- Late Ming women commonly wore cross-collar garments.

- While they often paired jackets with skirts (aoqun) or long robes with various collar styles, they also embraced skirt-over-top styles with wrap skirts or surround skirts (weichang).

- The “skirt-over-top” style of late Ming women involved tying a waist-high wrap skirt over a long robe, differing slightly from the Tang and Song ruqun or shirt-skirt (shanqun) styles.

The fashion of late Ming women was vibrant and diverse. Beyond the jacket-and-skirt (aoqun) or long robe styles where tops covered skirts, there was also a waist-high skirt-over-top approach.

Skirt-over-top means tucking the skirt as the outermost layer (think modern women tucking a shirt into a high-waisted skirt). Late Ming women often tied a skirt around their waist over their garments, creating a distinct look.

Indeed, the skirt-over-top style was widespread in late Ming, but it differed from the ruqun or shanqun of the Han, Jin, Tang, and Song eras, where short tops were paired with skirts. In late Ming, women typically wore long robes of any collar type and added a waist-high wrap skirt for the skirt-over-top effect. This extra skirt was optional, added for style or function based on personal needs.

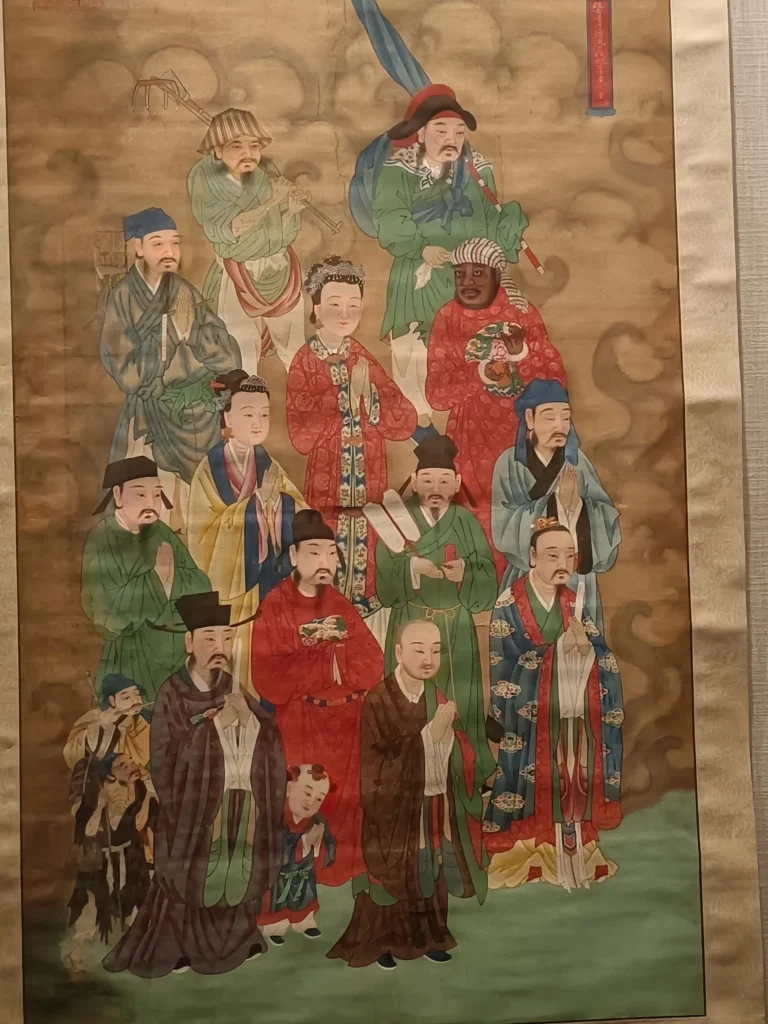

Take the round-collar, front-opening long robe as an example. A water-and-land painting from the Wanli era shows a woman in red, reflecting authentic attire of the time.

This confirms that such round-collar, front-opening robes were a recognized women’s style during the Wanli era. A mural from a Ming tomb in Jiyuan further shows a servant girl from the Wanli period, dressed in layers: an upright-collar inner layer, a cross-collar middle layer, a round-collar front-opening outer robe, and a draped scarf (pibo).

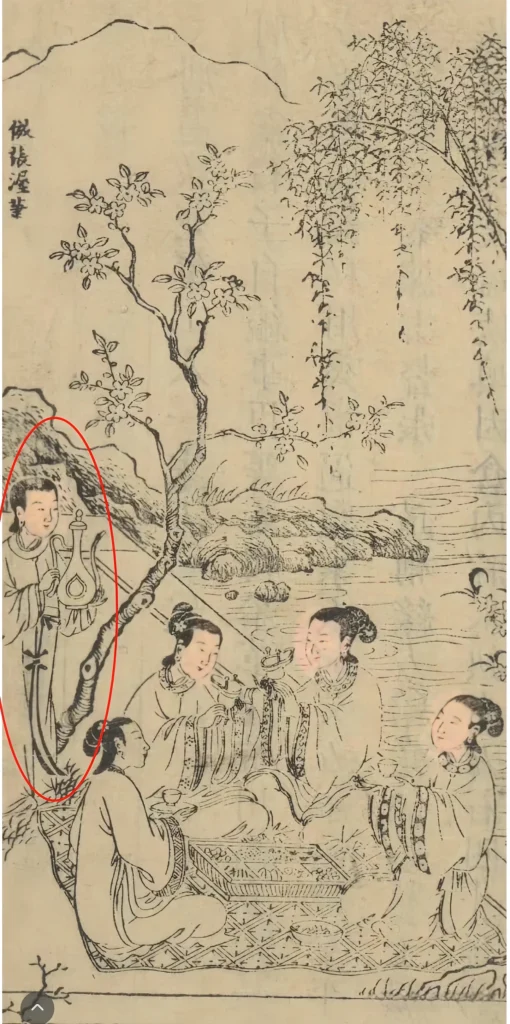

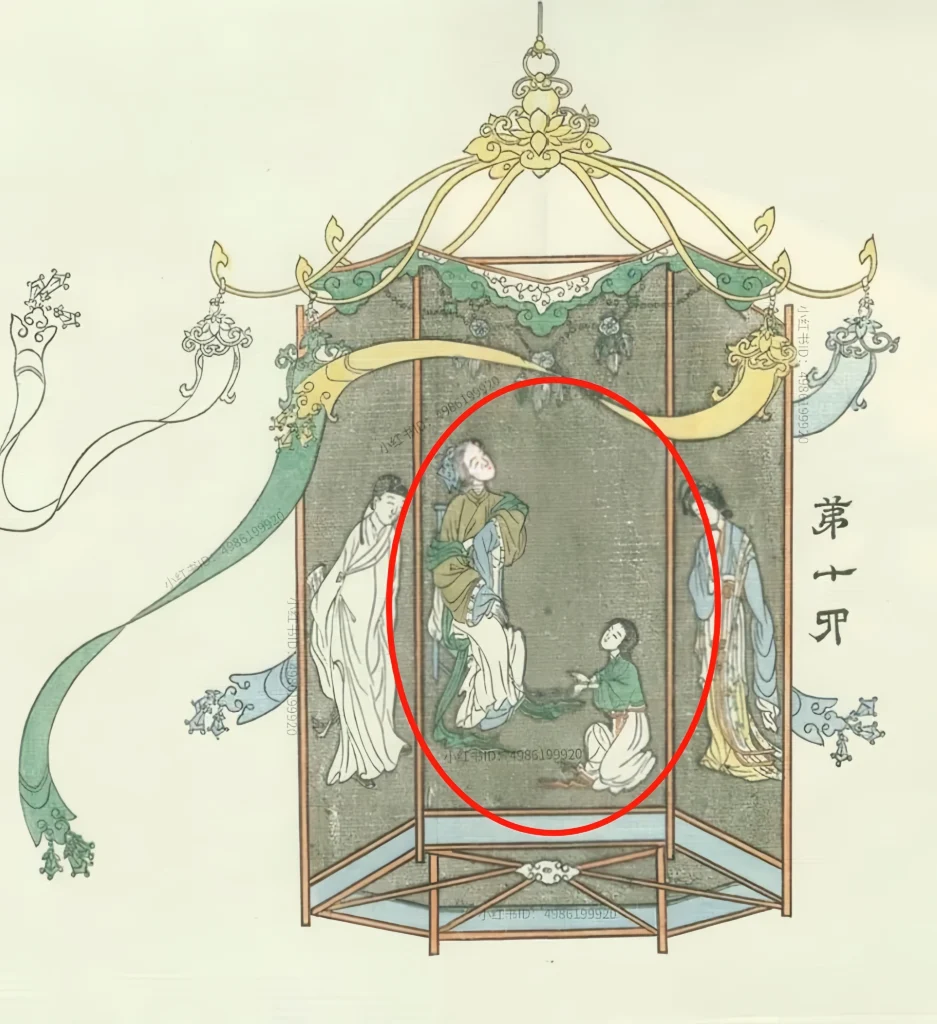

Clearly, this round-collar, front-opening long robe was a real everyday style in the Wanli era. Ming prints from the same period also depict women in round-collar, front-opening robes with a skirt tied at the waist, like the servant circled in red below:

Compared to other women in the image, this servant’s outfit aligns closely, matching the Jiyuan tomb mural’s outer robe style. The only difference? The circled servant has a skirt tied at her waist with a knotted sash hanging down.

These images clarify that, while simpler than her master’s attire, the servant’s round-collar, front-opening robe and cross-collar inner layer follow the same style. The unique addition of her waist-tied skirt with a knotted sash isn’t artistic exaggeration—it reflects practical clothing use.

The woman circled in red, wearing a round-collar, front-opening robe, ties a sash at her waist. Practically, this secures the long robe’s hem, making movement easier.

Thus, tying a skirt at the waist not only secured the hem for labor but also protected the main garment. Adding a wrap-around skirt initially served to shield clothing, later gaining decorative appeal. Even today, people wear aprons for housework or cooking to protect clothes. Aprons come in waist-tied or neck-strapped styles, born from utility but now styled for aesthetics, much like Ming skirts.

In the image, a woman swinging on a swing wears a skirt over her round-collar, front-opening robe, likely for both decoration and protection.

Is the skirt-over-top style an exception in late Ming? Far from it. Many late Ming women loved tying skirts over various long robes or shirts.

This applies to round-collar, front-opening robes, but what about round-collar, cross-lapel robes? Similar cases exist.

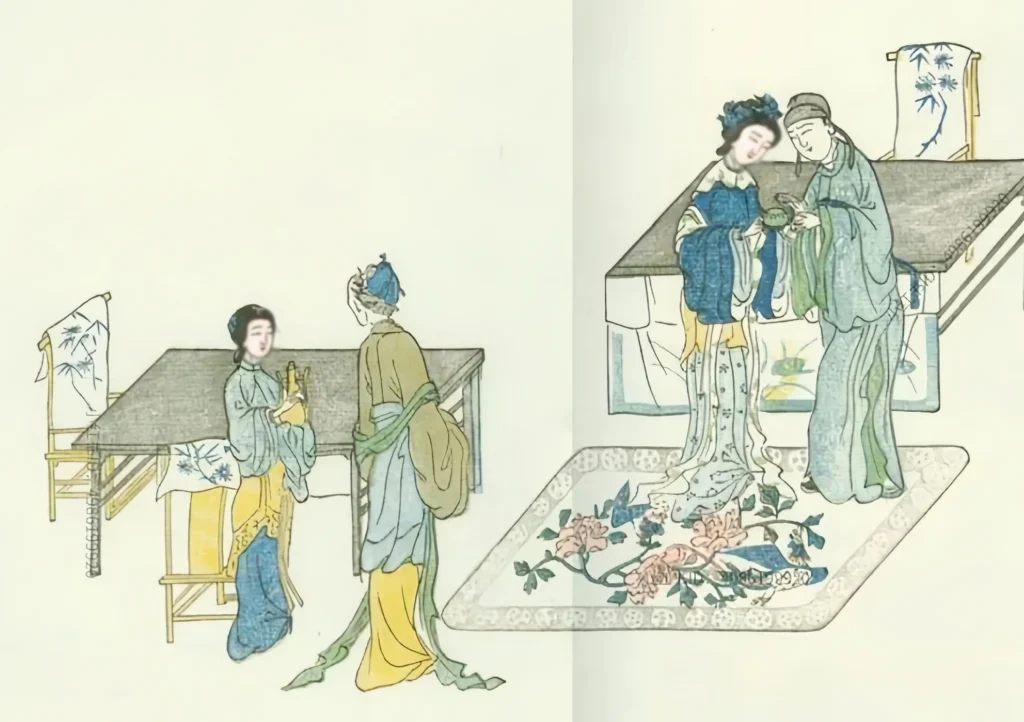

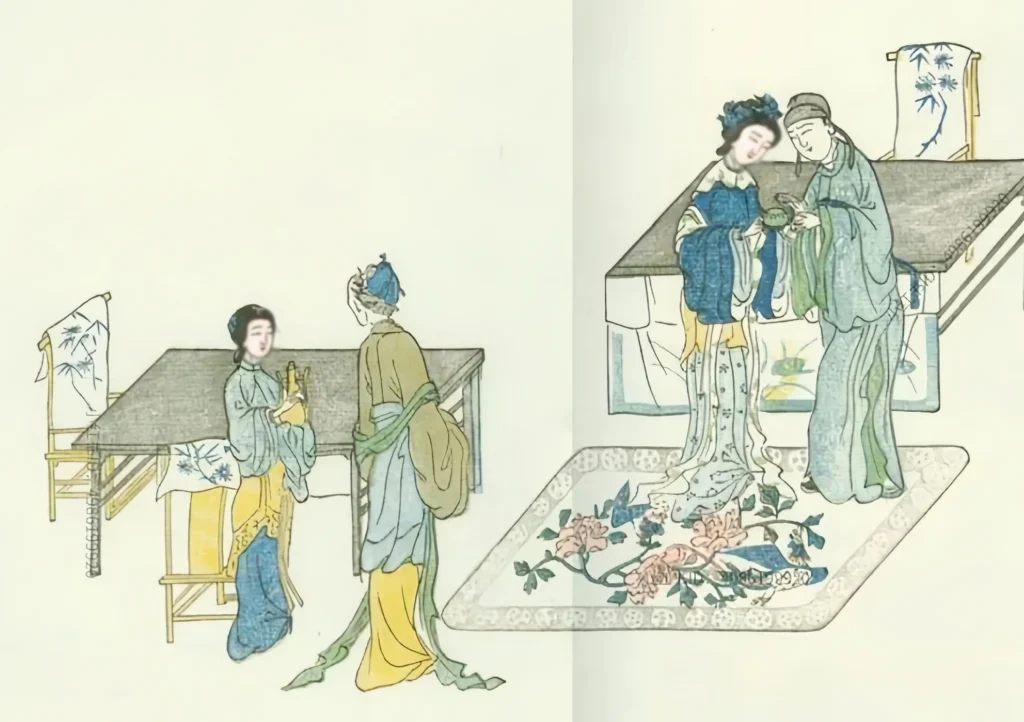

Based on the straight lines and shapes in front of the figures, the women in these images wear round-collar, cross-lapel robes or shirts with side slits. The left image shows a woman in such a robe, while the right image depicts servants with skirts tied over their outer robes.

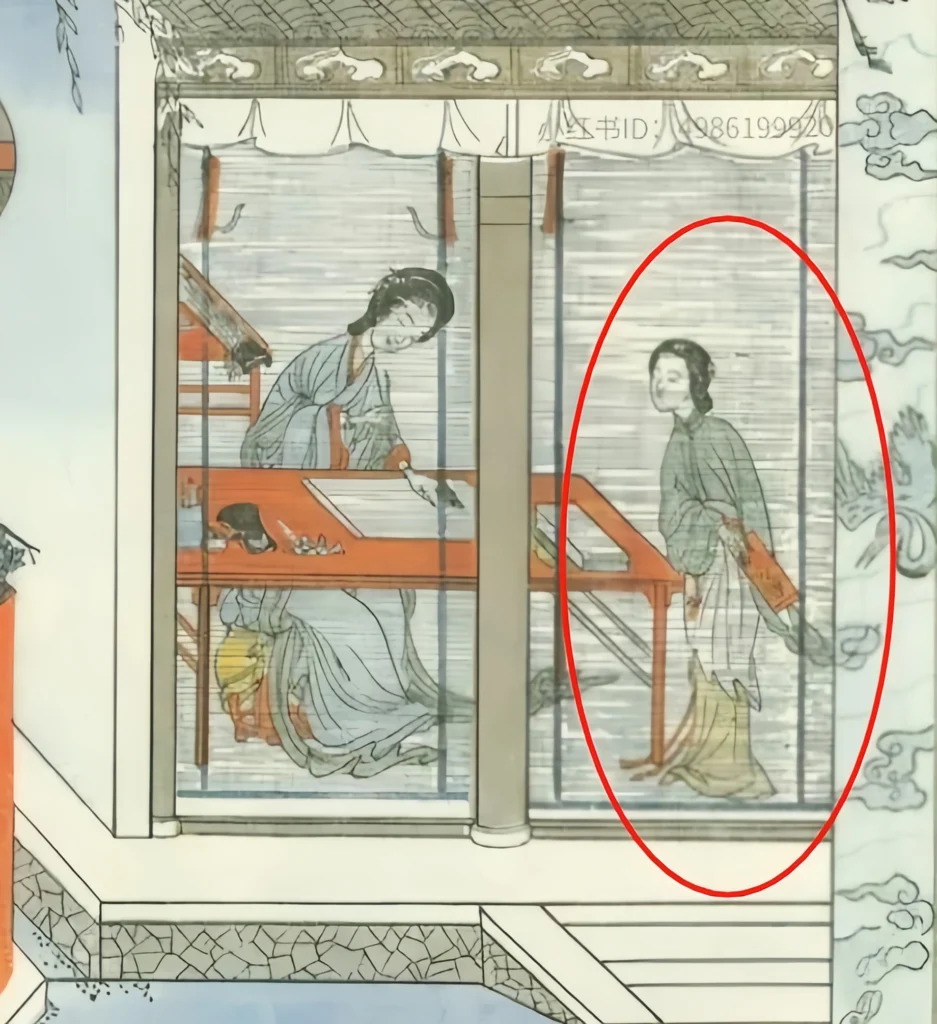

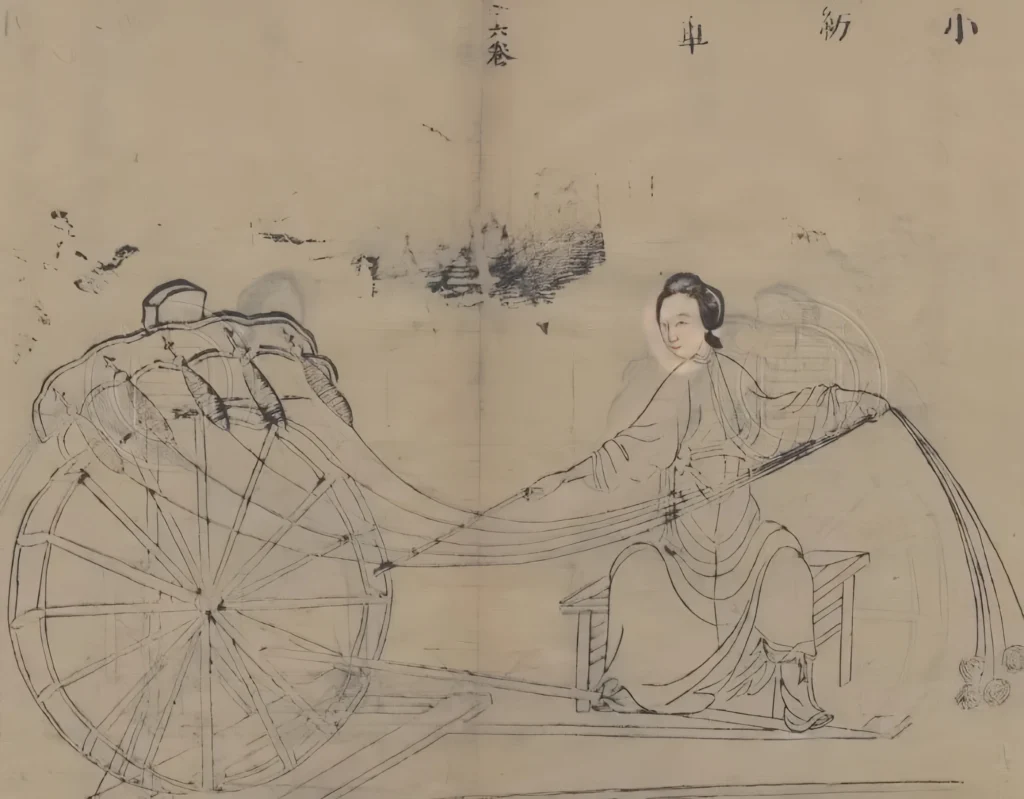

Similarly, the familiar late Ming upright-collar, cross-lapel long shirt (changshan) wasn’t just worn alone—it also appeared in skirt-over-top styles:

Since upright collars, cloud-shoulder yokes (yunjian), and hairstyles in these images are realistic, this colored Romance of the West Chamber print from the Chongzhen era naturally reflects women’s practice of adding skirts over long shirts. If it were fictional or imitating ancient styles, why not copy Tang or Song designs wholesale? Why bother depicting late Ming fashion trends?

Not just upright-collar, cross-lapel shirts—upright-collar, front-opening robes also show this style.

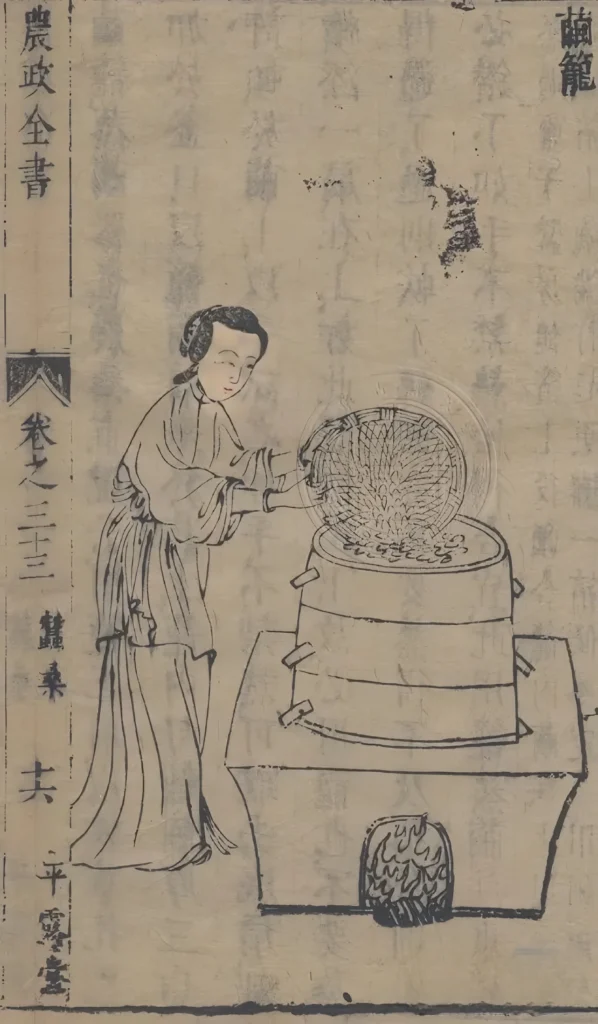

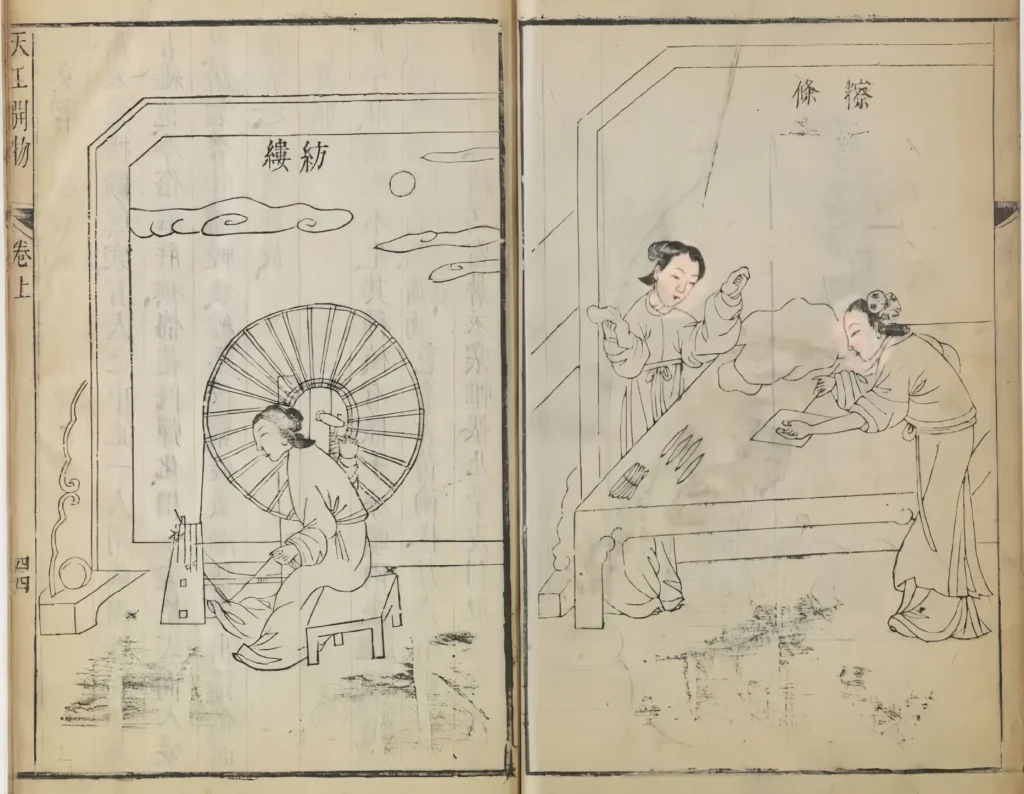

In the Chongzhen-era Tiangong Kaiwu, a woman’s image depicts an upright-collar, front-opening robe in a top-over-skirt (yi yan qun) style, consistent with other Ming artifacts. This proves the Chongzhen Tiangong Kaiwu wasn’t copying old templates but captured real late Ming scenes.

Where top-over-skirt exists, skirt-over-top follows:

If noblewomen’s portraits might be artistically embellished, laboring women’s images have no need for such exaggeration—they likely reflect objective depictions of work processes.

Similarly, late Ming’s Nongzheng Quanshu shows laboring women in upright-collar, front-opening robes with wrap skirts tied over them.

Not only laboring women—well-off women also wore upright-collar, front-opening robes with skirts tied over, though theirs leaned more decorative than practical compared to laborers.

Even front-opening jackets had cases with wrap skirts added.

The woman on the right wears an upright-collar, front-opening inner layer, a front-opening long robe, and a long skirt tied at the waist with floral knotted sashes.

If every skirt-over-top depiction were “fictional” or “imitating ancient styles,” why would all late Ming “realistic” robes consistently “fake” this one detail? Why assume the practical, common skirt-over-top style couldn’t exist in late Ming?

Or put it this way: late Ming artists faithfully drew upright or round collars and double buttons. Why would they suddenly add an “unrealistic” skirt to otherwise realistic figures?

As shown above, both women wear a red floral short jacket with a yellow striped skirt (aoqun). Why is the left one with a green wrap skirt “unrealistic,” while the right one without is “realistic”?

Splitting a single outfit to label skirt-over-top as unrealistic is absurd. From novels to technical manuals, courtesans to commoners, noblewomen to servants, this style existed historically. Why couldn’t late Ming women embrace both top-over-skirt and skirt-over-top? Why must it be one or the other?

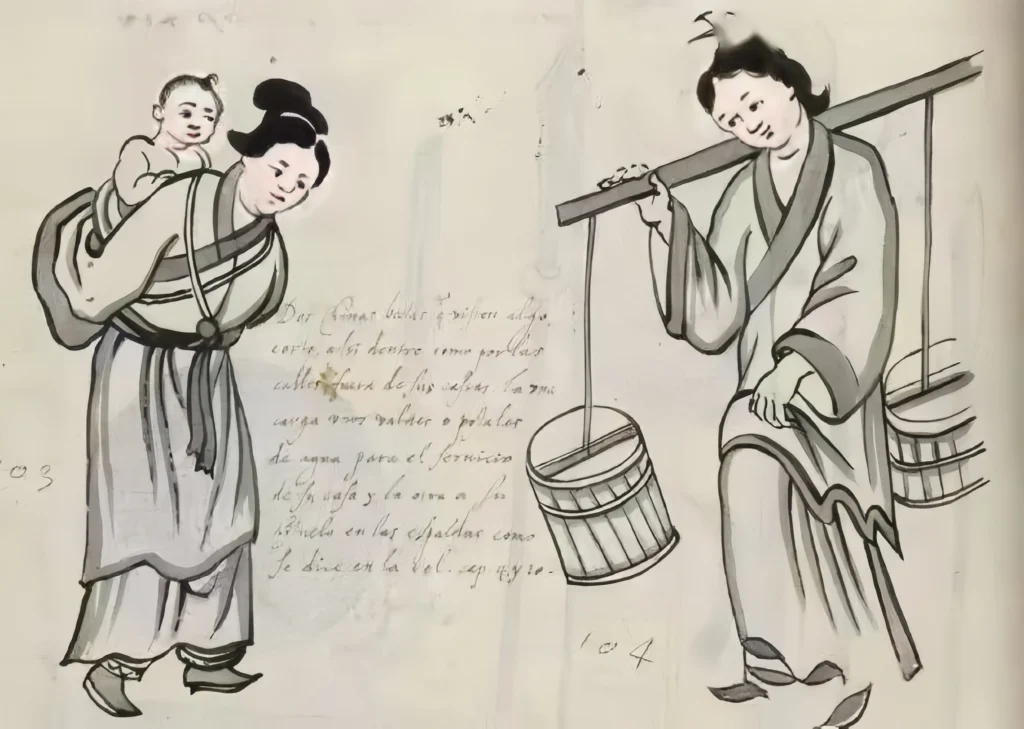

Many Ming paintings of laboring women clearly show commoners in cross-collar, waist-high ruqun. Some question if these are copied templates or artistic imagination.

Note this image: a woman carrying a child wears a cross-collar top with a cloth skirt tied at her waist, brimming with everyday life. There’s no reason for the artist to invent such a practical outfit.

One image clearly supports this article’s view: late Ming women typically wore cross-collar or other collar-style long robes or shirts, paired with skirts like horse-face skirts (mamian qun), with tops covering skirts. Like men, women wore long, uncut robes, as Chen Jiru (1558–1639) noted: “Women’s shirt sleeves resemble men’s clothing, with embroidered collars like lotus leaves half-covering the shoulders, called yunjian.” Three Strange Cases (Chongzhen 5th year, Zhengxiao Press) mentions late Ming merchants adapting men’s short Taoist robes into women’s jackets for rural women.

This shows that even in late Ming, cross-collar long robes were common for women, alongside upright-collar cross-lapel or round-collar front-opening styles.

During labor or activities, women tied a skirt—perhaps a simple apron, a horse-face skirt, or a decorative short skirt—over the outermost layer at the waist.

From this analysis, late Ming women wore top-over-skirt styles like aoqun and various long robes but also skirt-over-top styles with wrap skirts or surround skirts (weichang). This wasn’t artistic fantasy—it had practical meaning:

- Securing clothing: Like modern aprons or waist wraps, it kept garments in place during work.

- Protecting clothes: An extra skirt shielded the main outfit, like wearing durable clothes for cleaning today.

- Decoration: Wrap skirts added layers and elegance, with knotted sashes lending vintage charm.

Even today, layering clothes meets practical or fashion needs—think fake two-piece garments evolving from real layered looks, like short-sleeve over long-sleeve, vests over shirts, double skirts, skirts over pants, or hoodies with short skirts. Humans balance utility and aesthetics in clothing, so why would the practical, decorative skirt-over-top style vanish from late Ming life?

The late Ming skirt-over-top differs from Tang and Song ruqun or shanqun, where the top and skirt are essential components; without either, the look is incomplete. In late Ming, the outfit was already complete, and the skirt was an optional, functional, or temporary addition that didn’t disrupt the core style. Judging late Ming women by Tang or Song ruqun logic leads to misunderstanding. Still, we must rethink their fashion—skirt-over-top waist-high ruqun was a real, vibrant part of their wardrobe.

Legacy of Waist-High Ruqun in Modern Hanfu

Today, the waist-high ruqun inspires modern Hanfu enthusiasts, reviving the skirt-over-top style. Its blend of function and beauty, rooted in late Ming fashion, continues to captivate, as showcased in contemporary designs on platforms like China National Silk Museum. The waist-high ruqun remains a testament to Chinese Hanfu clothing’s enduring charm.

Responses