Exploring the Top 10 Traditional Chinese Music Instruments

In ancient times, sound was a pure delight, and creating it became a fun adventure for our ancestors, leading to the invention of all sorts of traditional Chinese music instruments. This time, we’re bringing you the top 10 Ancient Chinese instruments. Step into a paradise of Chinese musical heritage with us!

Top 10 Traditional Chinese Music Instruments

Drum

Back in the far-off days, drums were seen as a link to the heavens, mostly used as tools for rituals. They were a big hit during hunts and battles too. Drums as musical instruments kicked off in the Zhou dynasty. That era had the “eight sounds,” and the drum was the boss of the group—think “drum, qin, and se,” where the drum’s beat kicked things off before the strings played.

The cultural vibe of drums runs deep and wide. Those bold drumbeats marched alongside humans, guiding us from wild times to civilization. They could be the lively folk celebration drums or the classy beats for temple rites and palace feasts. From early clay drums, earth drums, skin drums, to bronze drums, they evolved into the many drum types we love today.

Drums are hands-down one of the most popular and widely used traditional Chinese music instruments. Some say the earliest drums came from ancient folks turning everyday stuff like clay pots or basins into sound-makers. Unearthed clay drums prove this—dating back 7,000 years to the Neolithic era, people were crafting them. These clay drums, also called earth drums, used baked clay frames covered with animal hide. China’s tradition of making drums with tile frames lasted a long time. The tao drum (or “rattle drum”) came from the northwest edges to the central plains, while the waist drum traveled from the Western Regions, booming in popularity during the Tang dynasty—some even used ceramic materials back then.

Drums showed up early, and finds like the earth drum from the early big tomb at Shanxi Xiangfen Taosi site confirm a 4,500-year history. In ancient times, drums weren’t just for rituals or dances—they scared off beasts, signaled alarms, or marked time. As society grew, drums found homes in ethnic bands, dramas, folk arts, dances, boat races, lion dances, celebrations, and work competitions. A drum’s simple setup—drumhead and body—makes sound when the hide vibrates from a strike or tap. China boasts tons of drum types, like waist drums, big drums, twin drums, and flowerpot drums, enriching the Chinese cultural instruments landscape.

Sheng

The sheng is an ancient Chinese instrument, one of the “eight musical instruments” (metal, stone, silk, bamboo, gourd, clay, leather, wood), with over 3,000 years of historical Chinese music history. Its reeds in each pipe create sound, making it the only harmonizing blow instrument and the only one that plays on both blow and suck. Its clear, bright tone, wide range, and strong vibe make it a standout.

It’s big in Guizhou, Guangxi, Hunan, Yunnan, and Sichuan. With a rich history, diverse shapes, and a bright, full sound, it’s packed with local flavor, often backing lusheng dances or band performances. Modern tweaks have brought it into ethnic orchestras, shining in solos, duets, or group plays with tons of expression, a true gem of traditional Chinese music instruments.

Xun

The xun is one of China’s oldest wind instruments, dating back about 7,000 years as part of ancient Chinese instruments.

Legend has it the xun started as a hunting tool called a “stone meteor.” Back then, folks tied a stone or clay ball with a rope, swinging it to hit birds or beasts. Some hollow balls whistled when spun, and people thought it was cool, so they started blowing them—turning stone meteors into xuns. Early xuns were made from stone or bone, later shifting to clay, with shapes like flat rounds, ovals, spheres, fish, or pears—the pear shape being the most common. The top has a mouthpiece, the bottom is flat, and the side has sound holes.

Over a long haul, around 4,000-5,000 years ago, the xun went from one hole (three notes) to two holes (four notes) as societies advanced. In late patriarchal or early slave times, finds like the one from Gansu Yumen Huoshaogou with three holes (four notes) show progress. By the late Shang around 1000 BCE, five holes allowed six notes. By the Spring and Autumn period (700+ BCE), six holes mastered the pentatonic and heptatonic scales—a 3,000-year journey in Chinese musical heritage!

Qin

In ancient times, a person’s cultural polish shone through the “four arts”—qin, chess, calligraphy, and painting—with playing the qin as the top skill among traditional Chinese music instruments.

The qin was invented in Fuxi’s time as a five-string instrument, some say by Shennong (Gu Shi Kao: Fuxi made qin and se; Gang Jian Yi Zhi Lu: Fuxi carved a qin from paulownia, strung with silk; Shuo Wen: Qin, a string instrument by Fuxi; Di Wang Shi Ji: Shennong crafted the five-string qin with palace, commerce, angle, sign, and feather tones). By King Wen’s era, two more strings—lesser palace and lesser commerce—were added. Its birthplace was likely the western Shandong-eastern Henan area (Fuxi’s capital at Henan Huaiyang, Shennong’s at Shandong Qufu).

Like the flute or xiao, the qin’s music could be enjoyed through walls. The “qin” character, from “now,” stresses “face-to-face play,” highlighting its solemnity—it was a high-class Chinese cultural instrument for noble guests, who sat upright like modern Westerners at classical concerts, reflecting cultural refinement and societal progress.

Se

The se’s roots stretch way back, dominating among unearthed string instruments as part of historical Chinese music. Most finds cluster in Hubei, Hunan, and Henan, mainly from Eastern Zhou Chu tombs, with sparse discoveries in Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, and Liaoning. Texts credit “Pao Xi” with its creation.

Legend says the se existed in the Xia dynasty. The Yue character in oracle bones tops with “silk” and bottoms with “wood”—since se needs strings, it likely came after silk-making. Pre-Qin string instruments were the qin and se, needing silk or nest-making tech for strings.

Another theory ties se to hunting bowstrings, possibly using cow tendon or animal hide, like the thick low strings in the 1984 replica of the Zeng Hou Yi tomb se, a key piece of ancient Chinese instruments.

Di

The di is a wind instrument, varying by region, with no reed—a hallmark feature. The “di” character falls in the “you” family, where “you” acts as both sound and meaning symbol, linked to “sliding” vibes. Its core meaning is “a bamboo tube where air slides through.” Debate has long swirled about when the Chinese musical heritage bamboo di began.

Recent digs in Zhejiang Yuyao Hemudu unearthed bone flutes resembling today’s six-hole di, dating back 7,000 years—possibly the oldest known traditional Chinese music instruments. Other finds include a Warring States seven-hole transverse copper di owned by an overseas Chinese, two transverse di from the Zeng Hou Yi tomb (433 BCE), two from Hunan Changsha Mawangdui Han tomb No. 3 (168 BCE), and a seven-hole two-section bamboo di from Guangxi Guixian Luobowan tomb No. 1—proof the di beats other instruments as an early gem.

Xiao

The xiao’s history traces back to ancient times. Chinese archaeology shows 7,000-year-old bone sound-makers, dubbed “bone whistles” (from Zhejiang Hemudu, now in Zhejiang Museum).

Made from bird limb bones with marrow removed, these hollow tubes—about 7 cm long, 6-8 mm wide, slightly curved—had two or three holes, producing a few notes, marking the birth of bone whistles as ancient Chinese instruments.

Though called whistles, their shape, structure, and sound principles mirror modern xiao and di, hinting at an early instrument form. Could these be the ancestors of xiao and di? Many wind masters today call them “bone flutes,” linking them to current designs. So, when did bamboo wind instruments start?

Lv Shi Chun Qiu notes: “Huangdi ordered Ling Lun to cut Kunlun bamboo for pipes.” Back then, China’s Yellow River area teemed with bamboo, shifting south to the Yangtze due to climate changes. Ling Lun’s bamboo pipes suggest New Stone Age instrument-making. Later, arranging his tuned pipes birthed the ancient panpipe. In Emperor Shun’s time, the “Shao” dance used “xiao” (today’s xiao), ushering a new era of Chinese cultural instruments. Da Xia, celebrating Yu’s flood control, had “nine movements” with “yue” (panpipe) accompaniment, known as “Xia Bamboo Nine Movements”—the panpipe’s precursor.

From Shao to Da Xia, the xiao shone in China’s music history. The Zhou “eight sounds” (metal, stone, silk, bamboo, gourd, clay, leather, wood) listed “bamboo” for xiao and chi. The Zeng Hou Yi tomb find gave us a firsthand look at this traditional Chinese music instrument, so “silk and bamboo” naturally evokes it.

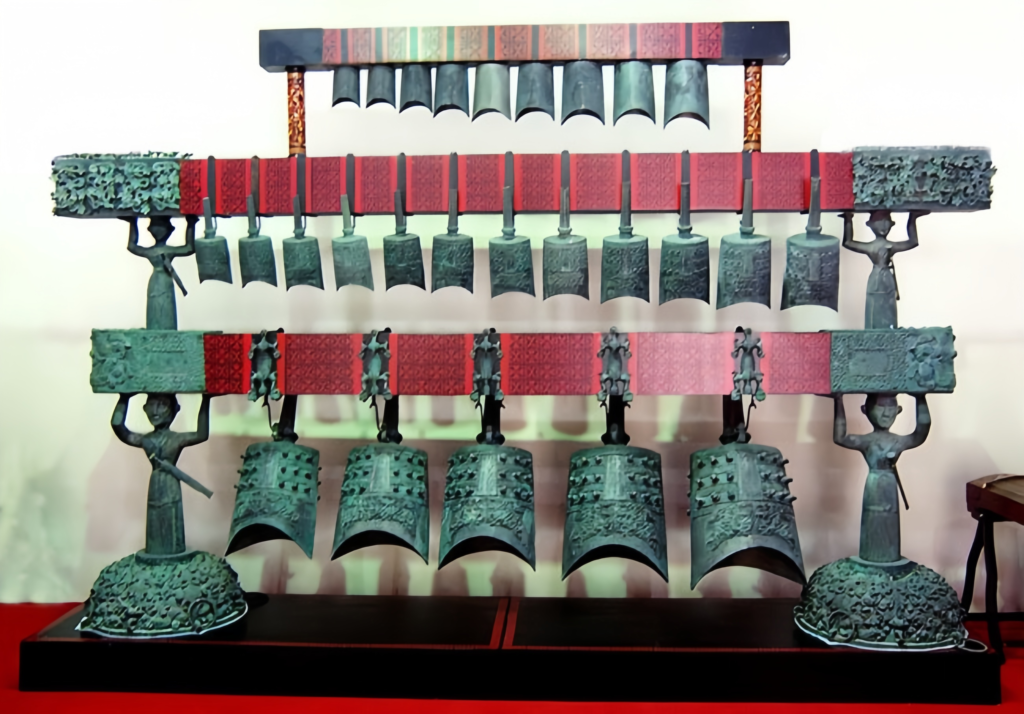

Bianzhong

Bianzhong first appeared in the Shang dynasty, often in sets of three or five, playing melodies as part of historical Chinese music. Their unique oval shape featured simple beast-face designs.

By the mid-to-late Western Zhou, sets grew to eight, producing two notes a minor or major third apart, often gracing palace feasts as “bell and drum music” with traditional Chinese music instruments.

In the mid-to-late Spring and Autumn period, sets expanded to nine or thirteen.

Post-Qin and Han, palace ya music used rounder bianzhong with a single note per bell, a big shift after a 500-year golden age that later faded.

In Sui and Tang, beyond ya music, bianzhong featured in “Nine-Part Music” and Tang’s “Ten-Part Music” like Qing Music and Xiliang Music, rarely reaching folks. Tang poets praised their loud, resonant, and sweet tones. From Song to Qing, bianzhong casting skills faded, and bell music waned. Qing palace bianzhong, with different shapes and off-key tones, strayed from the rich Chinese musical heritage.

Erhu

The erhu, also called “huqin,” emerged in the Tang as “xiqin,” later “jiqin” in Song. It’s thought to evolve from xiqin into today’s captivating bowed string instrument, a standout in Chinese cultural instruments. It can express deep sorrow or grand scenes.

A key bowed instrument in China’s music family, the term “huqin” appeared in Tang, naming Western and Northern ethnic imports. By Yuan, Ming, and Qing, it became the go-to for bowed strings.

Soulful Two Springs Reflecting the Moon, tear-jerking River Waters, flowing Sanmenxia Fantasy, and epic Great Wall Fantasy are standout pieces. In the 1920s, erhu’s rise as a solo instrument owes much to Hua Yanjun (Abing) and Liu Tianhua. Masters’ innovations made it a top solo and orchestral string voice.

The erhu’s wooden body, python-skin end, and two metal strings (inner d1, outer a1, a perfect fifth apart) offer rich techniques: left-hand slides, harmonics, trills, glides, plucks; right-hand continuous, separate, staccato, jumps, tremolos, flutters, and picks. Its range spans three to four octaves.

Pipa

Early pipa shapes differed from today’s, mainly in its round form versus the modern pear shape. Qin-Han pipa were straight-necked—“straight” meaning a straight handle. With a round body, West Jin’s Ruan Xian (of the Seven Sages) mastered it, naming it “ruan” after him.

Today’s “pipa” usually means the curved-neck version (though straight-neck types like the Tang five-string pipa in Japan’s Shoso-in exist), with a backward-bent handle and half-pear body, brought from Turpan to Northern Zhou in Wei-Jin-Northern-Southern dynasties.

Sui Shu · Music Records: “During Emperor Wu of Zhou, a Turpan man, Su Zhipo, entered with the Turkic queen, skilled at hu pipa, playing seven tones in one mode.” Played horizontally with a plectrum, it was free-style—unlike formal instruments requiring upright posture—even doable on horseback. Southern pipa and Japanese pipa still use this hold. Wei-Jin-Northern-Southern dynasties saw a Hu culture wave; Yan Shi Jia Xun notes a Qi scholar teaching his 17-year-old son Freshman and pipa, hinting at its trend. Back then, pipa mainly accompanied. Sui Shu · Music Records: “Turpan… songs like Shanshan Mani, tunes Pogari, dances Little Heaven, and Shule Salt.”

The Tang Dunhuang Pipa Score (933 CE) from Mogao Caves shows pipa’s big leap under Li Tang rule, a hit for festivals and dances with traditional Chinese music instruments. It later split into schools, shifting to vertical play with fake nails.

Ancient pipa had four bridges with 13-15 frets, now up to six bridges with 18, 24, 26, 28, or 30 frets, tuned to 12-tone equal temperament, spanning A-g3 for a 28-fret version. Right-hand techniques include pluck, pick, double-pluck, roll, split, hook, wipe, sweep, wheel, half-wheel; left-hand slides, trills, lifts, presses, ghost notes, twists, harmonics, pushes, pulls, glides, and notes. It handles chords and harmonies. Classics include Ambush from Ten Sides, The King’s Armor Removal, Xunyang Moonlit Night, Yangchun Snow, and Princess Zhaojun’s Departure, showcasing the depth of Chinese musical heritage.

Keen to learn more? Learn More About Hanfu for deeper insights into Hanfu traditions, ideal for anyone eager to explore traditional fashion.

Responses