The Cultural Charm of Hanfu Accessories

Xiang Nang (Fragrance Pouch)

Xiang Nang, also called Xiang Dai or Hua Nang, isn’t the same as a purse. It’s a folk embroidery craft born from ancient working women, a product of the male-farming, female-weaving farm culture, carrying on a timeless tradition.

Today’s pouches are woven with colorful silk threads. Crafters embroider ancient, mystical patterns on silk, stitching them into small, varied-shaped pouches filled with finely ground herbs for a strong, sweet scent. In the past, they perked you up, some using spices—loved by many, later switching to pure fragrance. Some were sewn from scraps, stuffed with herbs like Angelica, Chuanxiong, Scutellaria, Patchouli, Kaempferia, Saussurea, and Peppermint, worn on the chest for a nose-tickling aroma. Sui Shi Guang Ji, citing Sui Shi Za Ji, mentions a “Duan Wu pouch” made with red and white fabric, threaded with colorful strings into a flower shape, and a “clam powder bell” stuffed with clam powder in cloth, padded with cotton like prayer beads for kids to soak up sweat. These carry-along bags evolved from sweat-absorbing powder to evil-repelling charms, coins, or realgar powder, finally becoming spice-filled pouches—now a refined Duan Wu folk art. Materials vary—jade carvings, gold or silver filigree, kingfisher feather inlays, or silk embroidery—shaped into rounds, squares, ovals, waisted corners, gourds, pomegranates, peaches, or victory blocks. Most are two-piece with hollow middles or drawstring tops, always with holes for scent to waft out. About 10 cm long, 5 cm wide, 2 cm thick, they feature a top hanging cord and a bottom tie with lucky knots or jewel tassels. Ingredients include Atractylodes, Kaempferia, Angelica, Calamus, Agastache, Patchouli, Chuanxiong, Cyperus, Mint, Citron, Magnolia, Mugwort, plus Borneol, and optionally Suxiang, Yizhi, Galangal, Tangerine Peel, or Linglingxiang. A copper-carved “longevity” pouch might use single-sided flannel, shaped and colored as needed.

Xiang Nang Legend: During the An Shi Rebellion, Emperor Xuanzong fled west with Yang Guifei. At Mawei Slope, the army stalled, and he sacrificed her to take the blame for the chaos. After her strangling, she was hastily buried. Post-reconquest, Xuanzong had her remains moved, and an eunuch found only her bones, but the fragrance pouch on her chest was intact. The aging emperor, seeing it, wept, recalling Li Mountain’s joys. Eighty years later, poet Zhang Hu penned Tai Zhen Xiang Nang Zi: “Gold-stitched pouch, her old scent lingers, who for the king unravels this, a lifetime of regret tied to the heart.”

Shan Zi (Fan)

Originally a round fan, now covering all fan types. Zhu Zi Yu Lei (Vol. 94) says: “A fan is just a fan—moving is its use, still is its form.” China’s fan culture runs deep, blending bamboo, Daoist, and Confucian vibes.

China’s dubbed the “fan-making kingdom.” Fans first appeared as “Wu Ming Fans,” said to be Shun’s creation. Gu Jin Zhu • Yu Fu by Cui Bao notes: “Wu Ming Fans, made by Shun after receiving Yao’s throne, to broaden vision and seek advisors—used by Qin-Han nobles and scholars.” Types include feather, palm, pheasant, round, folding, silk palace, gold-dusted, black paper, and sandalwood fans. Ancient roots trace to hot summers when ancestors grabbed leaves or feathers, shaping them to block the sun—hence “sun shield.” Early fans, like reed “Men” or “Shan,” were power symbols for rulers, not just for cooling, but to flaunt status as ceremonial fans, often called “palace fans.” Post-Sui-Tang, feather and silk fans boomed, with scholars treating them as “elegant sleeve treasures,” waving them while reciting poetry—sparking fan-themed works like Li Qiao’s Fan, Bai Juyi’s White Feather Fan, and Tang Yi’s Ode to a Broken Fan.

In ancient times, a scholar without a fan was like a hipster without a pet dog—lacking flair. By Qing, even officials, accountants, and everyday folks rocked fans to “pose.” Fans merged carving, weaving, knotting, and calligraphy arts. The two main handles, or “big bones,” bear inscriptions; the many “small bones” or “hearts” feature inlays or lacquer, like gold-star coral with red base and silver flecks. Fan heads offer over 100 styles—bamboo joints, plum blossoms, vases, or gourd tips. Pendants in jade, peach pits, or olive nuts, with tassels, sway gracefully. Embroidered cases are pretty, durable, and handy. Sandalwood or bone fans sport intricate cutouts or burnt designs with varied ink shades. Beyond summer cooling, fans starred in storytelling, opera, dance, and comedy as props—both functional and decorative.

Ying Luo (Jewelry Necklace)

Ying Luo refers to jewel- and gem-linked pieces, while silk-embroidered ones are Ying Luo. It blends necklaces and long-life locks into one. The top is a metal collar, hung with various gems, and sometimes a lock-like piece dangles near the chest.

In ancient China, Ying Luo doubled as a collar or lock term. Dream of the Red Chamber (Chapter 8) shows Jia Baoyu pestering Xue Baochai to see her gold lock. She relents, saying, “Someone gave me lucky words, carved on it, so I wear it daily; otherwise, it’s just heavy.” She unbuttons her red jacket, revealing a sparkling, golden Ying Luo.

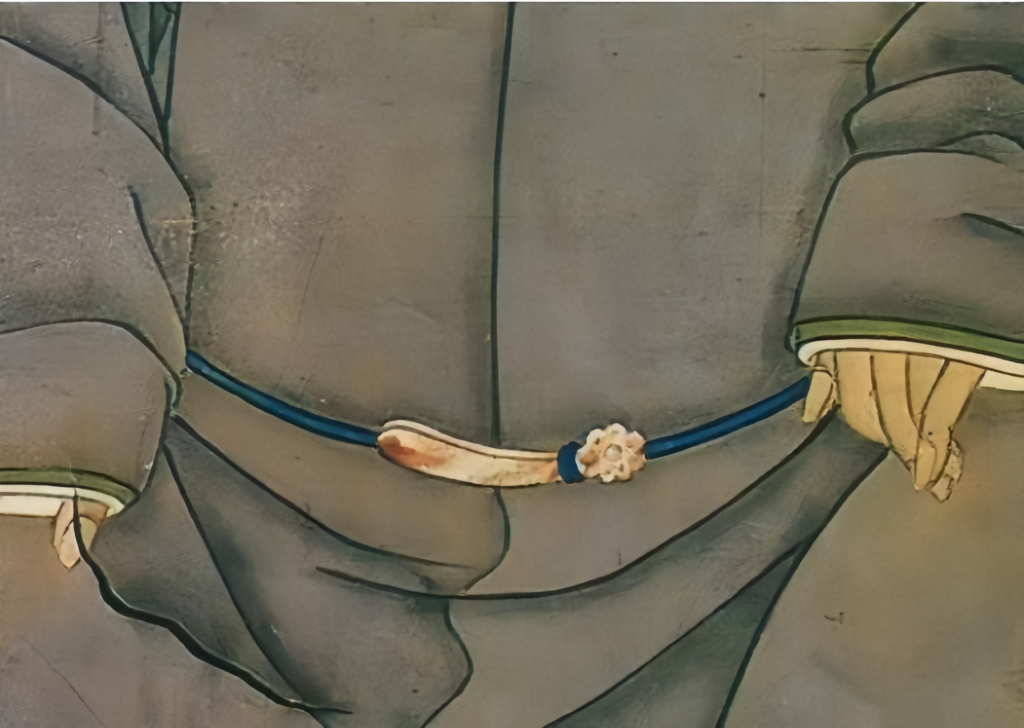

Yao Dai (Waist Belt)

Early Chinese clothes skipped buttons, using small ties called “Jin” at the collar—Shuo Wen • Xi Bu: “Jin ties the garment.” Duan Yucai notes: “Joins the collar, unlike today’s buttons.” To keep clothes secure, a big belt, or Yao Dai, was added at the waist—different from modern pant belts, serving a unique role.

Ancients valued it highly, wearing belts with official or casual wear, especially for ceremonies.

Li Ji • Shen Yi specifies: “Belt below avoids the thigh, above avoids the ribs, at the boneless spot.” Kong Yingda explains: “If over a bone, it’s hard to adjust—ideal for ritual belts, worn higher.” Yu Zao adds: “Belt one-third down, sash takes two—about 4.5 feet below.” Placement varied by garment style.

Shou Zhuo (Bracelet)

Bracelets serve three vibes: showing status and personality, beautifying arms, and boosting health. They’re usually worn on the left wrist—gemmed ones snug, plain ones loose. Only pairs go on both wrists.

“Why seal our bond? Twin bracelets encircle,” goes an old line. “Tiao Tuo” was one ancient name. Tang Shi Ji Shi by Ji Yougong tells of Emperor Wenzong quizzing ministers on “light shirt with Tiao Tuo” from a poem—none knew. He revealed, “Tiao Tuo is today’s wristband.” Ancient tales often feature women gifting bracelets to lovers—Zhen Gao by Tao Hongjing notes fairy E Lu Hua giving Yang Quan gold and jade Tiao Tuo; Liao Zhai Zhi Yi • Bai Yu Yu has a scholar Wu meeting a purple-clad fairy, who gifts her gold wristband as a memento.

As a love token, its role faded, but it remains a stunning wrist accent for girls, quietly linking classical and modern vibes—many unaware of the old vows tied to jade bracelets.

Responses