Seasonal and Auspicious Motifs in Ming Dynasty “Jifu”

Ming auspicious clothing (jifu)

Ming auspicious clothing (jifu) was a new clothing category that took shape during the Ming Dynasty. It evolved from the earlier concept of “auspicious garments” and referred to clothing worn for seasonal festivals, weddings, birthdays, banquets, and other celebratory occasions. By the Qing Dynasty, Ming auspicious clothing officially became a recognized category within the imperial dress system.

Traditionally, the term “jifu” referred to ceremonial garments used for auspicious rites, such as major state sacrifices, with mianfu being a typical example. As society developed and festive occasions became more frequent, there arose a need for a distinct type of celebratory attire. During the Ming Dynasty, garments worn for weddings, formal celebrations, and seasonal festivities—more formal than everyday wear—were collectively referred to as Ming auspicious clothing. Although Ming jifu were not formally codified in dress regulations, they appear frequently in institutional records and literary works.

The Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty records: “Three days before and after the Emperor’s Birthday Festival, all wear Ming auspicious clothing.”

The Wanli Yehuo Bian notes: “Embroidered Uniform Guards attending court all wore black caps and Ming auspicious clothing.”

In Jin Ping Mei, Chapter 39, it is written: “Ximen Qing changed into a bright red Ming auspicious clothing embroidered with multicolored lions, fastening a gilt rhinoceros-horn belt at his waist.”

In The Tale of Marriages to Awaken the World, Chapter 44, one finds: “At the auspicious hour, Su Jie was invited out, dressed in a bright red patterned Ming auspicious clothing, paired with an official-green embroidered skirt, her jade ornaments complete—like an immortal descending to the mortal world.”

Ming auspicious clothing did not follow a single standardized form. Their silhouettes were the same as everyday or casual clothing, including round-collared robes, straight-cut garments, yisa, tieli, Daoist robes, and jacket-and-skirt ensembles. Colors favored festive tones such as bright red; for officials, the red round-collar robe often served as Ming auspicious clothing. Compared with ordinary clothing, Ming auspicious clothing featured more elaborate decoration, commonly using Ming seasonal motifs or motifs carrying auspicious meanings.

During the Wanli period, the Nanjing censor Meng Yimai wrote in a memorial to the emperor:

“For the Emperor’s Birthday Festival, there are longevity robes; for the Lantern Festival, lantern robes; for the Duanwu Festival, Five-Poison Ming festival clothes; and for annual ceremonies, dragon robes.”

Longevity robes were worn on imperial birthdays and featured motifs such as the character shou (longevity). Lantern robes were worn during the Lantern Festival and decorated with lantern patterns. Five-Poison Ming festival clothes were worn at the Duanwu Festival, using imagery of the Five Poisons. Dragon robes featured dragon motifs. These garments were all typical examples of festival Ming auspicious clothing, with decorative themes closely tied to the time and occasion.

Liu Ruoyu’s Zhuozhong Zhi records in detail the seasonal changes in clothing materials and the festival-specific Ming seasonal motifs used throughout the year.

After the Kitchen God sacrifice on the 24th day of the twelfth lunar month, palace women and eunuchs wore gourd-patterned rank badges and mangyi. On the fourth day of the third month, they changed into silk gauze garments. On the fourth day of the fourth month, they switched to sheer silk. From the first to the thirteenth day of the fifth month, they wore Five-Poison and mugwort-tiger badges with mangyi. On the seventh day of the seventh month (Qixi Festival), magpie-bridge motifs were worn.

In the eighth month, autumn flowers such as begonia and hosta were admired in the palace; rank badges with jade rabbit motifs excavated from Dingling were likely used for the Mid-Autumn Festival. On the fourth day of the ninth month, garments were changed again, featuring chrysanthemum motifs for the Double Ninth Festival, while winter clothing was aired in preparation for cold weather. On the fourth day of the tenth month, zhusi silk was worn. In the eleventh month, warm ear coverings were bestowed upon officials. During the Winter Solstice, palace women and eunuchs wore yangsheng badges and mangyi.

Rank badges (buzi) were square or round decorative panels worn on the chest, back, or shoulders of officials and nobles to indicate rank. On Ming auspicious clothing, however, rank badges could feature Ming seasonal motifs and were not strictly tied to hierarchy.

By comparing surviving Ming garments and embroidery with descriptions in Zhuozhong Zhi, the characteristics of Ming auspicious clothing motifs become clearer.

Gourd Motifs From the Kitchen God sacrifice through the New Year, gourd motifs—also known as “Great Auspicious Gourd”—were used. In the palace, gourd-patterned badges were often combined with dragons or mang motifs.

Lantern Motifs The Lantern Festival on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month was marked by lantern-viewing, and garments featured lantern patterns to enhance the festive mood.

Five Poisons The Duanwu Festival on the fifth day of the fifth month used motifs of the Five Poisons—scorpion, snake, gecko, centipede, and toad—to warn of seasonal dangers. Tigers and mugwort were added as “mugwort tigers,” symbolizing the power to ward off evil.

The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl The Qixi Festival on the seventh day of the seventh month commemorates the annual meeting of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl. As celestial beings, their depiction emphasized divine dignity rather than romance, creating compositions that were solemn and well suited to the court environment.

Jade Rabbit The Mid-Autumn Festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month often featured jade rabbits and full moons.

Chrysanthemum The Double Ninth Festival on the ninth day of the ninth month involved climbing heights and drinking chrysanthemum wine, making chrysanthemum motifs a natural seasonal symbol.

Yangsheng (Rising Yang) The Winter Solstice marked the return of yang energy. Motifs showed a ram exhaling auspicious vapor, playing on the homophony of “yang” (sheep) and “yang” (positive energy).

Winter garments also featured the “Ram Prince” motif. Classical drama describes “Three Ram Princes,” a homophone for “Three Yang Bring Prosperity.” Palace records note sheep-themed imagery used during the Winter Solstice. In Ming paintings, the Ram Prince appears in winter attire, carrying plum branches and birdcages with magpies—symbolizing joy—surrounded by lambs to represent abundant descendants, echoing the meaning of the “Hundred Sons” motif.

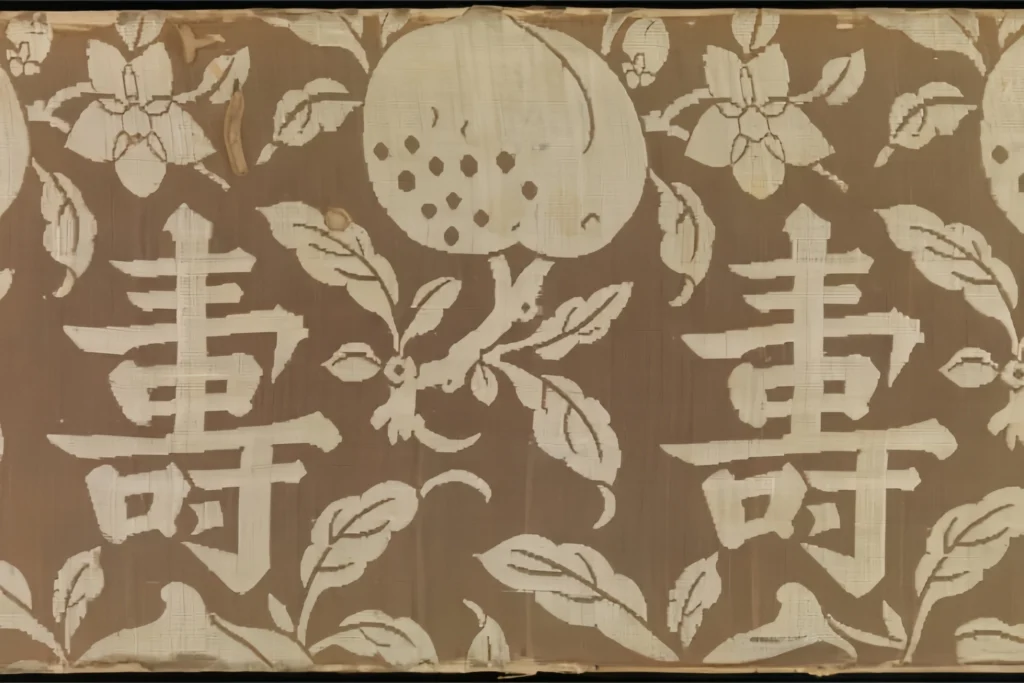

Longevity motifs were especially common, reflecting the universal desire for health and long life. Imperial birthday celebrations produced many surviving Ming auspicious clothing. Designs often featured lingzhi mushrooms, cranes, and peaches, or prominently displayed characters such as “shou” or “ten thousand longevity,” expressing blessings in a direct visual language.

Ming auspicious clothing design also excelled in combining themes. Seasonal motifs were often paired with birthday symbols, creating layered meanings of double joy. A notable example is the birthday pattern of the Wanli Emperor, born shortly after Mid-Autumn Festival. Palace garments combined longevity symbols with jade rabbit imagery, many examples of which were excavated from Dingling.

Because Ming auspicious clothing emphasized visual impact and festive appeal, they often relaxed strict hierarchical rules. As a result, clothing transgressions were most visible in Ming auspicious clothing, such as commoners wearing phoenix crowns or officials using five-clawed dragon motifs. Old Tales of the Capital records extravagant festival Ming festival clothes that was worn once and pawned afterward to fund new garments the following year.

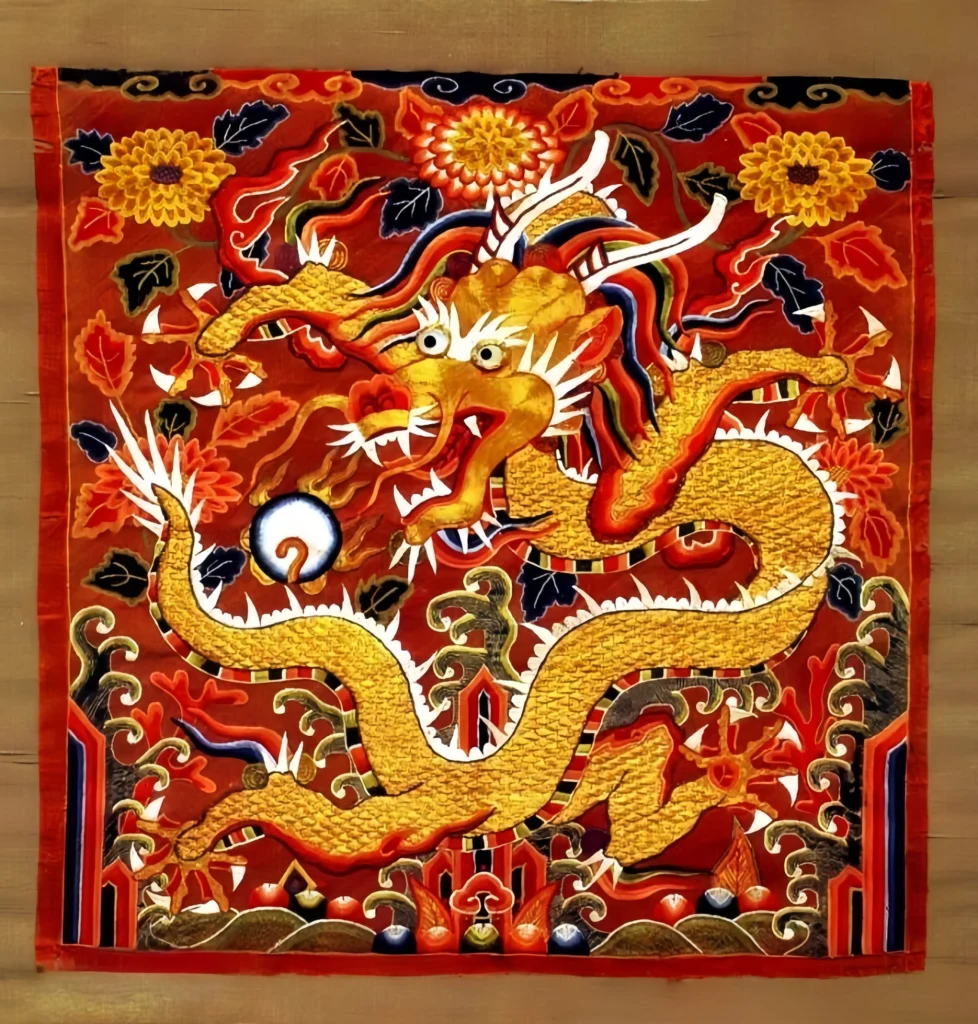

Two major decorative systems defined Ming auspicious clothing. One used cloud shoulders (yunjian), sleeve bands (tongxiu lan), and knee bands (xilan), creating garments known as tongxiu robes or xilan robes, often decorated with auspicious creatures such as dragons, mang, qilin, phoenixes, and cranes.

(Collection of the Duke Yansheng’s Residence)

The other system was the influential Eight-Roundel pattern, with motifs arranged on the front, back, and sleeves. This later evolved into ten- and twelve-roundel designs and became standard in the Qing Dynasty, continuing into the Republican period and even influencing traditional opera costumes.

Over time, Ming auspicious clothing patterns evolved in complexity and style, but their formal and celebratory nature remained consistent. In modern society, garments worn for weddings, ceremonies, or festivals—whether Western bridal gowns, traditional phoenix coronets, long robes, or modern festive attire—can all be seen as contemporary forms of Ming auspicious clothing. As interest in traditional culture grows, the design principles and symbolic language of historic Ming auspicious clothing continue to inspire modern fashion.

Want to explore more Ming auspicious clothing?

Check our Hanfu Styling Guide for authentic tips!

Responses