Hanfu: The Ru Ao (襦袄 / Top Jacket)

What Is Hanfu Ruqun? The Classic Top + Skirt Combo

The Hanfu ruqun is the upper garment in the traditional “upper garment and lower skirt” system. According to legend, the ancient image of Emperor Yan (Shennong) showed him dressed in a red Hanfu ruqun. Its basic structure stayed consistent throughout Hanfu history, though its length and width changed over time. As Yan Shigu noted in his annotation of Jijiu Pian: “A long garment is called pao, reaching the tops of the feet. A short garment is called ru, ending above the knees.” A long Ru reaches from the upper thigh to the knee, while a short Ru falls between the waist and upper thigh.

The Ru is unlined, and when padding or lining is added, it becomes the Ao. For this reason, some believe that an unlined Ru is similar to a shan, while a lined Ru is closer to an Ao – the classic Hanfu top.

The Qin terracotta warriors show that long and short Ru shared similar features: right-over-left closure, cross-collar, and curved hems. The difference was that high-ranking military officers wore double-layer long Ru, while lower-ranked warriors wore single-layer ones. In addition to the standard cross-collar, some terracotta warriors in Pit 1 also show unique collar variations where one side of the collar folds outward into different shapes, such as long triangles, small triangles, and narrow strips. Some even have an extra collar piece between the inner and outer collars.

Since the Ru has both long and short versions, why is it still described as a “short garment”? This is in contrast to the Shenyi. In the Book of Rites, the Shenyi is described as a garment where the upper and lower parts are connected and edged with decorative trims. It states: “Short, but not exposing the skin; long, but not touching the ground.”

The Shenyi reaches the ankles, so compared to it, the Ru is indeed a short garment. Another commentary notes: “When worn with an outer garment, it is called a middle garment. With plain edging, it is called a long garment.” This suggests that Shenyi had different names depending on how it was worn. It was mainly an underlayer.

However, in ancient literature, Ru was often mentioned without distinguishing length. For example, Xin Yannian’s Yulinlang includes the line: “Long skirt with a paired belt, wide sleeves with a harmonious Ru.” In A New Account of the Tales of the World, it is recorded that “Han Kangbo, when only a few years old and living in poverty during a severe winter, owned only a Ru, which his mother sewed for him.” Su Shi also wrote in The Pavilion of Joyful Rain: “If heaven rained pearls, the cold could not use them as Ru; if heaven rained jade, the hungry could not use them as grain.”

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, the Ru was everyday wear for commoners (including servants), while the Shenyi (also called the long or middle garment) was used by nobles for court and ritual occasions. Commoners used the Shenyi as formal wear. Because the Ru was short and convenient for labor, it became the daily clothing of working people in the Han Dynasty, typically worn with trousers.

Those who wore Hanfu ruqun with skirts would tuck the skirt into their waist while working. Those wearing Ru and trousers often rolled up their pant legs. Laborers usually wore hemp Ru. The elderly tended to wear long Ru similar to robes. By the Eastern Han, long Ru had become widespread among the general population.

During the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties, long-term division and cultural blending led to dramatic changes in clothing. Baopuzi records: “Nothing stays constant; everything shifts — long then short, wide then narrow, high then low, rough then fine. Decoration changes according to preference.” Traditional clothing rules were challenged. Two major changes occurred: Han clothing norms were broken, and elements of nomadic dress were absorbed. Under the influence of Hu clothing, northern men wore short garments with tied trousers, leather belts, pullover jackets, windproof hats, and short boots. In the south, Han clothing styles of the Qin and Han remained more consistent.

In the Qin and Han periods, colors like blue and purple were valued, while common people could only wear white. But during the Wei and Jin, fashion shifted dramatically, and white became the favored color. As Confucian ritual systems weakened, traditional rules regarding garment styles, colors, and dressing methods were no longer strictly followed. New trends emerged: people went barefoot, bareheaded, wore open-chested garments, layered robes and skirts, or adopted unusual outfits—completely breaking previous norms.

In the Sui and early Tang, the Ru was short, with narrow sleeves, tucked into the skirt, and mostly used as an inner layer. From mid-Tang onward, Tang hanfu Shan-Ru gradually became wider, to the point where Emperor Wenzong had to issue a decree limiting sleeve width to no more than 1.5 feet. Influenced by Hu clothing, the Tang also saw the rise of lapel-style Ru and Ao. During this period, the Hanfu ruqun became mainly women’s clothing. Overall, Ru in the Tang hanfu evolved from tight and narrow to loose and wide, and commonly appeared in colors like white, blue, pink, green, yellow, and red.

By the Song Dynasty, the government repeatedly emphasized simple and modest clothing, and garments were required to be “tight at the neck, waist, and hem.” Under Confucian influence, plain, elegant, and restrained styles dominated the aesthetics of the era. The Song hanfu Ru became narrower and longer, usually with small sleeves and a straight collar, known as the xuan’ao. The boundaries between Ru, Ao, and pao became blurred, and they were gradually grouped under the category of Ao. Long Ru also merged with the robe, eventually being referred to collectively as pao.

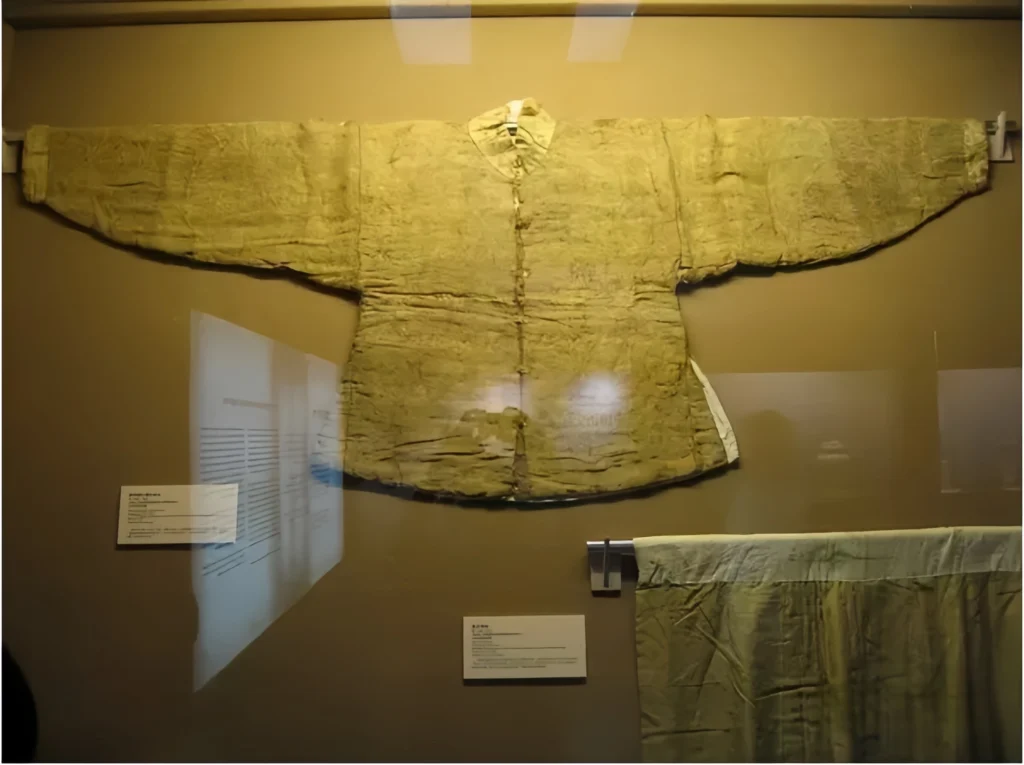

As more people began wearing Ao, its meaning became clearer. The Ao was mainly for autumn and winter, made from thicker fabrics with lining—called the lined Ao. When padded with cotton, it became a cotton Ao; when lined with fur, it became a fur Ao. Over time, the term Ru faded from use.

During the Yuan Dynasty, a unique form of Ao appeared: the bianxian ao. It preserved the style of Central Plains clothing but incorporated Mongol features. It had a round collar, narrow sleeves, a flared hem with tight pleats, and a broad waistband made from braided strips. Some versions also had buttons and were commonly called “waistline jackets.” Although it originated during the Jin, it became widely used in the Yuan. It was first worn by attendants and guards, but later adopted by general officials, and even high-ranking figures wore it in the late Yuan and into the Ming Dynasty.

In the Ming Dynasty, the Ao was everyday clothing for common people. Its most notable feature was the use of front buttons instead of the traditional tying method—a major innovation reflecting changing times.

The Hanfu ruqun, as a core outfit combining upper Hanfu top and lower skirt, was forcibly prohibited during the Qing Dynasty due to the “hair-cutting and clothing reform,” which targeted clothing with strong Han identity. However, the evolved form—the Ao—survived because it was practical and easy to wear. Its two main styles were the standing-collar right-lapped jacket and the standing-collar front-opening jacket, typically worn with trousers and a waist skirt by laborers. From the early 20th century onward, the men’s Ao gradually shifted toward the front-opening style.

Ready to wear your own Hanfu ruqun?

Check our Hanfu ruqun guide for patterns and shops!

Responses