A Concise History of Hanfu, Utterly Elegant!

China’s vast history and rich culture shine through in Hanfu history, the story of traditional Chinese clothing that embodies elegance and ritual. Known as Huaxia yiguan, Hanfu reflects the harmony of heaven and earth with its flowing robes and intricate designs. From the Yellow Emperor’s innovations to the Ming dynasty attire, Hanfu has evolved over millennia. Today, the Hanfu revival brings this timeless attire back to life. Join us as we explore five pivotal eras in Hanfu history and why it captivates the world in 2025!

The Dawn of Hanfu history: Xianqin and Shang Dynasty

Upper yi and lower shang symbolize the harmony of heaven and earth; round sleeves and jiaoling reflect the cosmic order of round heaven and square earth; the central seam and hanging belt embody human righteousness. “Ruling the world by letting clothes hang” represents the political ideal of stability and harmony; “correcting attire” corrects one’s demeanor and character. The unparalleled elegance of towering crowns and broad belts, the timeless poetry of flowing luoyi, whenever thought of, captivates the heart

Hanfu history begins in the Xianqin period, when early humans used animal hides for warmth and modesty. The Yellow Emperor formalized Huaxia yiguan with the “upper yi, lower shang” system, symbolizing cosmic order. By the Shang dynasty, youcen jiaoling upper garments (yi) with narrow sleeves and weishang lower garments (shang) became standard. A bixi apron prevented exposure, while pao garments connected yi and shang for practicality. This era laid the foundation for traditional Chinese clothing, setting the stage for centuries of elegance. Learn more about ancient Chinese culture at The British Museum.

In the distant Xianqin period, early people lived primitively, using animal hides for warmth, then for modesty, taking the first steps toward civilization. After the Yellow Emperor took charge, he created the xingzhi of upper yi and lower shang, spreading it across the land. The term “yishang” originated from this. “Upper yi, lower shang” symbolizes the order of heaven and earth. For a long time, this was the standard attire of ancient Chinese people.

Yi refers to the upper garment, which by the Shang dynasty had a youcen jiaoling upper garment, mostly with narrow sleeves, reaching the knees; shang, in contrast to yi, broadly includes lower garments like pants, qun, or jingyi (crotchless pants). In this period, shang typically meant a weishang, a tight-fitting lower garment, fan-shaped when spread out, tied at the waist with a cord. To prevent exposure, a bixi, like an apron, was worn in front of the shang.

At the same time, garments connecting the upper and lower parts appeared. For example, pao was a long garment combining yi and shang, with an outer and inner layer.

Ritual and Chaos: Chunqiu and Zhanguo Periods

Before the Chunqiu period, the guanzhi system was incorporated into “ritual governance,” with colors indicating status distinctions. Black, white, red, qing, and yellow were zhengse, symbolizing nobility, used for ceremonial attire; gan (reddish-blue), red (light red), piao (light qing-red), purple, and liuhuang were jiancai, symbolizing lowliness, used for casual clothing, undergarments, linings, and attire for women or commoners.

In the Guofeng·Beifeng·Lüyi of the Shijing, “green yi, yellow lining” uses jiancai for the outer garment and zhengse for the inner, which, from a ritual perspective, was considered improper. One theory suggests this poem was written by Zhuang Jiang, wife of Duke Zhuang of Wei, expressing her sorrow over losing favor to a concubine. In reality, with the collapse of ritual and music in the Chunqiu and Zhanguo periods, such violations became commonplace. Confucius, frustrated by people wearing colorful clothing out of context, lamented, “I detest purple usurping red.”

“The Duke of Qi loved purple clothing, and the state had no other color. The King of Chu loved slender waists, and many in the palace starved to death.” Like the chaos of the Chunqiu and Zhanguo periods, clothing and aesthetics disregarded rules. The trend of “what the ruler loves, the people exaggerate” inevitably influenced the rise and fall of states. Ultimately, Qin unified the six states.

In the Qin and Han periods, “the six kings fell, and the four seas became one,” as Qin Shihuang established an unprecedentedly unified state. Unity extended beyond land to currency, measurements, writing, and wheel gauges—things integral to daily life. In clothing, influenced by the Five Elements, black was favored (Zhou’s totem was fire; Qin succeeded Zhou with water virtue, and black represents water). Commoners wore white pao, and prisoners wore zhe (ochre) clothing. The xingzhi followed the existing upper yi and lower shang as formal ceremonial attire.

Shenyi gradually became everyday wear.

Shenyi, also a long garment combining upper yi and lower shang, differs from pao by cutting the yi and shang separately and sewing them together, wrapping the body to conceal it, hence the name. It existed as early as the Chunqiu and Zhanguo periods. It reached the ground, concealing the feet when walking.

Plain yi with zhu-lined collar is shenyi. Bo is an embroidered collar. Shenyi comes in two types: zhiju shenyi and quju shenyi. Quju extends the rear hem into a triangular shape, which, when worn, wraps around the hips and is tied with a silk cord.

Zhiju evolved from quju, removing the wrapping hem and adopting a flat, square hem. This change was due to early crotchless pants requiring quju’s coverage. Thus, before the Han, the standard sitting posture was kneeling then sitting.

Shenyi’s collar is distinctive, typically using jiaoling with a low neckline to reveal underlayers. When wearing multiple layers, each collar was visible, sometimes three or more, called “sanchongyi.”

After the Han dynasty was established, though it favored yellow for earth virtue, it largely followed Qin’s system. By the Eastern Han under Emperor Ming, the “guanzhi inheriting Zhou” mianguan system was established. Thereafter, while each Han dynasty had unique traits, the main features remained consistent, forming a continuous tradition. The following attire patterns emerged: mianguan with upper yi and lower shang was the most formal ceremonial attire for emperors and officials; paofu (shenyi) was the everyday attire for officials and scholars; ruqun was favored by women; laborers wore short yi on top and long pants below.

In the Han yuefu poem Moshang Sang, the young and beautiful Luofu, while picking mulberries, wore ruqun. Ruqun is a form of “upper yi, lower shang.” The upper garment, called ru, is short, reaching the waist; the lower garment, called qun, is a waist-tied long skirt, wrapping the lower hem of the ru, secured with a silk waistband. It gives a narrow-top, wide-bottom, stable, and graceful appearance.

In the mural described, the woman on the far right wears a zhu-red short ru with jiaoling and black-edged collar, large sleeves with white edges; her lower qun is a flared waist-tied long skirt, loose, comfortable, yet graceful and splendid.

With long qun paired with silk bands and short ru with large sleeves embroidered with hehuan, the wine-selling Hu Ji in Yulin Lang was the most fashionable woman on Han dynasty streets.

Grand and heavy, layered and flowing, Han dynasty attire profoundly influenced later eras. Changing the calendar and attire colors became a way for emperors to assert legitimacy after seizing power.

Freedom and Flow: Wei, Jin, and Nanbeichao

In the Wei, Jin, and Nanbeichao period, in 220 CE, Cao Pi overthrew Han, marking China’s entry into the Wei, Jin, and Nanbeichao period of constant regime changes. Despite a brief unification under Western Jin, most of the time was marked by war and division until the Sui dynasty reunified the south and north in 589 CE. The turmoil of chaotic times bred a pessimistic social atmosphere.

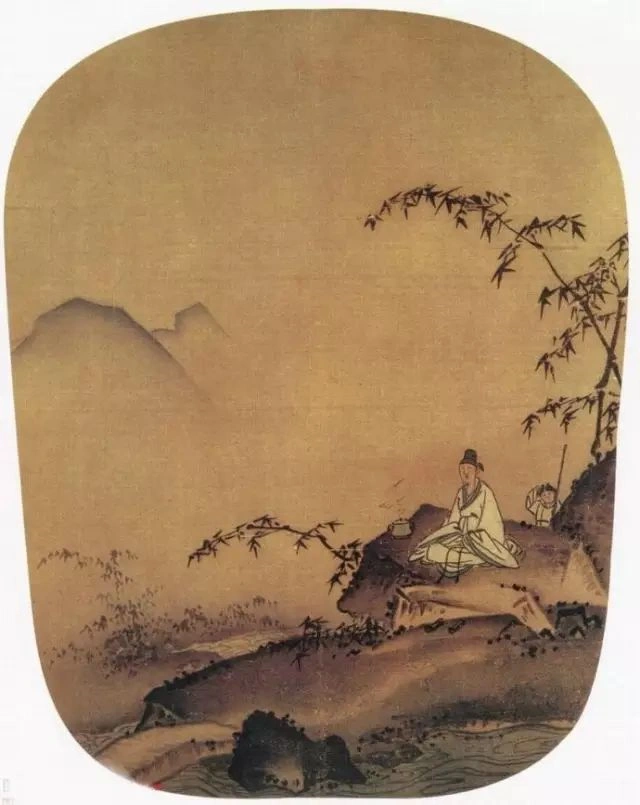

Literati and scholars oscillated between decadence and passion, escaping reality by advocating quietism while pursuing personal liberation and unrestrained behavior: drinking, playing music, indulging in nature, taking cold-food powder, and exploring Daoism and Buddhism. In attire, this manifested as a pursuit of freedom, elegance, and nonchalance. Men’s long yi became simpler and more casual. Wide shan and large sleeves with broad belts became a hallmark.

To show disdain for ritual propriety, they wore a long, large-sleeved shan, called dashanxiu. Unlike Han pao, its cuffs were wide and uncontracted. It came in jiaoling or duijin styles but was often worn with the collar open, chest exposed, exuding a carefree, breezy demeanor.

This trend influenced women’s clothing. Large sleeves fluttered, long qun trailed the ground, with floating bands tied between the waist and weishang, layered and increasingly complex and splendid.

Among them, a ceremonial garment called zaju was intricately made and stunningly beautiful. A variation of shenyi, its lower hem was cut into triangular decorations, with weishang at the waist and long floating bands extending, creating a graceful, fairy-like movement.

In the Northern Dynasties, ruled by ethnic minorities, attire was heavily influenced by hufu. Yuanling (curved collar) narrow-sleeved dan yi and paofu were fashionable. By the Sui and Tang, originating in the north and unifying the realm, yuanling styles spread widely, becoming the primary collar type for paofu thereafter.

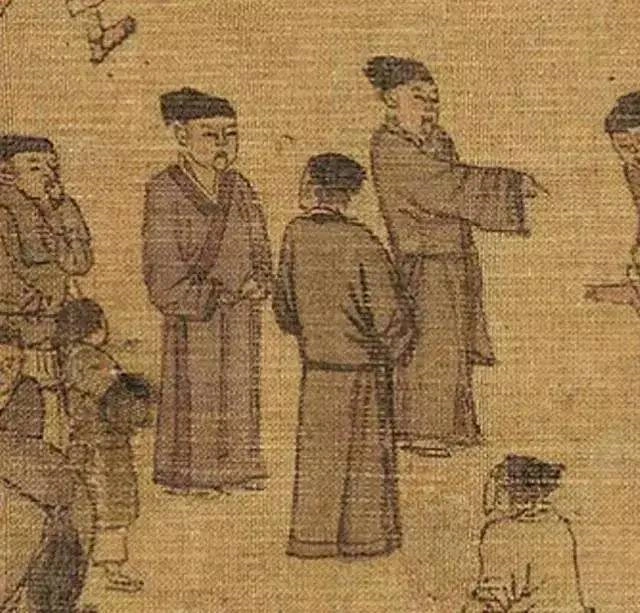

The Sui and Tang are well-known as the peak of China’s feudal society. With unprecedented frequent foreign exchanges and ethnic integration, they showcased the inclusive nature of Chinese civilization. In attire, this manifested as a blend of styles. Men’s attire inherited the jiaoling youcen mianguan yishang of Han tradition.

Status was distinguished by clothing color.

Unity and Shenyi: Qin and Han Dynasties

“Above third rank wore purple, fourth rank deep fei, fifth rank light fei, sixth rank deep green, seventh rank light green, eighth rank deep qing, ninth rank light qing.”

Lighter colors indicated lower status.

Yellow became exclusive to emperors, with huangpao as their patent.

“Qing, hong, zao, bai” marked the divide between official and commoner attire colors.

Under diverse cultural influences, the yuanling pao from the Northern Dynasties became a common attire. From emperors and officials to commoners, it was widely worn.

Pinnacle of Style: Sui, Tang, and Beyond

The Sui and Tang dynasties blended cultures, making Huaxia yiguan vibrant and inclusive. Tang women’s tanling ruqun and shiliu qun, paired with sheer shaluoshan, exuded confidence. Men wore yuanling pao, with colors indicating rank. The Song dynasty favored refined beizi and luosha qun, while the Ming dynasty attire restored Han traditions with feiyufu and xiapei. The Hanfu revival in 2025 draws heavily from these eras, blending tradition with modern flair. See Tang fashion at China Daily

Tang women also pursued freedom. Due to cultural inclusivity, attire styles proliferated, with greater exposure than before.

Tang women’s attire was grand and majestic. First, colors were vibrant, often mixing bright red and purple without appearing vulgar; second, fabrics were light and flowing, like silk bands in the breeze. Especially the tanling, it showcased unprecedented aesthetic confidence and openness.

Women’s ruqun abandoned wide sleeves. The upper ru was shortened with narrower cuffs, and the lower qun was raised from below the chest to above it. Paired with flowing pibo, it was graceful without bulk, giving an elegant, slender appearance.

A new style emerged: tanling ruqun. The upper garment’s collar abandoned duijin or youcen jiaoling, adopting a collarless, chest-exposing style, reaching the waist.

Some paired it with a short-sleeve upper garment called banbi. Worn externally, it evolved from Han-Wei banxiu. Initially, because it “didn’t cover the elbows,” it was practical for labor and popular among commoners. Nobles used it as casual home attire. Wei Emperor Ming, Cao Rui, was once criticized by officials for wearing banxiu, deemed improper. By Sui and Tang, banbi became fashionable in the palace and gradually a favored women’s garment.

Banbi collars came in duijin or jiaoling styles. The placket was sometimes decorated with silk bands tied together, appearing fresh, lively, and capable.

The most famous lower qun was the shiliu qun.

Legend says Wu Zetian captivated Li Zhi with a shiliu qun. After Li Shimin’s death, Li Zhi ascended, and Wu Zetian was sent to Ganye Temple. To express her longing and ensure Li Zhi remembered her, she used a shiliu qun as a token, deeply moving him. Defying norms, he brought her back to the palace, launching her legendary rise. Paired with the blood-red shiliu qun was often a wide, sheer daxiushaluoshan. This was a common Tang women’s pairing. The skirt waist was raised to cover the chest, with only a moxiong inside, draped with a shaluoshan, faintly revealing the skin.

Every smile radiated softness, every glance was enchanting. Breaking the past rule of “men and women not sharing attire,” women wearing men’s clothing became a trend. The grand Tang, splendid and romantic, was unmatched. Some say in the Tang, if flowers didn’t bloom fully, it was deemed immoral. Such splendor was never seen again in later feudal dynasties.

The Song dynasty was a period of contraction. Though it emphasized economic and cultural development, Northern Song never recovered the Yanyun Sixteen Prefectures, a lasting regret; Southern Song retreated to the south. This led to conservative thought and a preference for refined elegance. In attire, unlike Tang’s openness, it prioritized coverage, presenting a rational beauty. Besides inheriting Tang styles, it focused on restoring Han ethnic clothing traditions.

Men continued “upper yi, lower shang,” with lower garments as qun or pants. Official attire was mainly yuanling lanshan, also called yuanling lanshan. (Lanshan is a garment connecting upper and lower parts.) The waist had ornate daiwei for rank distinction.

Commoners could also wear it, with a horizontal lan at the hem to reflect the old upper yi, lower shang system.

Scholars favored hechang, often used as a casual outer coat. Hechang, originally a Daoist garment, symbolized ascending to immortality. This large-sleeved long shan, worn externally, was wide and flowing, “worn by gentlemen, carefree and at ease.”

Women’s attire abandoned Tang’s extravagance and vibrancy. It prioritized simplicity and elegance, appearing slim, delicate, and long.

Narrow-sleeved upper yi, floor-length high-waisted qun, paired with a long pibo. Song ruqun largely followed previous styles, with changes in details. For example, the upper ru had a higher collar, and colors were more subdued. Compared to Tang’s grandeur, it was a delicate, refined, and touching beauty.

The most iconic Song clothing style was the beizi (also written as “back zi”), a straight-collared duijin long shan wearable by both genders. With long, narrow sleeves, it reached the knees, with parallel unstitched front flaps, fastened with buttons or cords, worn as the outermost layer.

Beizi’s colors and patterns were simple yet refined, paired with ruqun, revealing scattered qun edges below. Subtle yet not bare, gracefully hazy, balanced in tone, it exuded an ethereal charm.

Song women also favored luosha qun.

Qun and waistbands were prized for length, with fine pleats to make the qun appear longer.

As light fabrics were prone to blowing, they hung a jade yuhuanshou on the waistband to weigh down the qun, preventing undergarment exposure.

Unlike the commoners’ refined style, palace consorts and noblewomen preferred a stable, serious style. Daxiushan was their most common attire, named for its wide sleeves. This garment perfectly embodied understated luxury. Simple in appearance, it was intricate in detail. Hem and sleeve edges used gold techniques like weaving, appliqué, or pasting, making it exquisitely beautiful. Common women couldn’t wear it.

Pursuing elegance and quality, the Song people were rational and refined. Unfortunately, with the rise of Neo-Confucianism, natural desires were subtly suppressed. Foot-binding became a trend, and women’s attire ceased to have exposed forms.

In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang declared himself emperor in Nanjing, founding the Ming dynasty. That year, he sent Xu Da, Chang Yuchun, and others to conquer Dadu, ending Yuan rule nationwide. The Yanyun Sixteen Prefectures, ceded by Shi Jingtang of Later Jin in 938, returned to Han control, reestablishing a unified dynasty. Having lived under Yuan rule, Zhu Yuanzhang prioritized restoring Han ethnic rituals, establishing a clothing system “inheriting Zhou and Han, drawing from Tang and Song.”

Officials wore wushamao and yuanling pao.

Paofu had rank-specific colors, with buzi (patches) on the chest and back, their embroidered patterns indicating rank differences.

Paofu colors were fei for ranks one to four, qing for five to seven, and green for eight to nine.

Eighth-rank and below officials’ gongfu had no patterns.

Feiyufu was a Ming-exclusive garment, awarded by the emperor to trusted aides, a mark of honor.

It was adorned with feiyu patterns, identical on front and back.

Feiyu resembled mang patterns with two horns, plus fins and a tail.

Scholars and literati often wore blue or black long pao, called zhishen.

This pao was jiaoling, loose, and knee-length.

Paired with zhishen were rujin or sifang pingding jin.

Commoners wore panling yi and avoided xuan, purple, green, liuhuang, jianghuang, and minghuang colors.

Women’s clothing styles mostly imitated Tang and Song. Due to Neo-Confucian influence, they were more conservative. For example, upper garments lengthened to cover the body more fully, and exposed qun lengths shortened. In daily wear, the banbi from Sui and Tang evolved into a collarless, sleeveless duijin mid-length upper garment called bijia.

Song’s beizi in the Ming could reach qun length. Typically, noblewomen wore large-sleeve styles, while commoner women wore narrow sleeves.

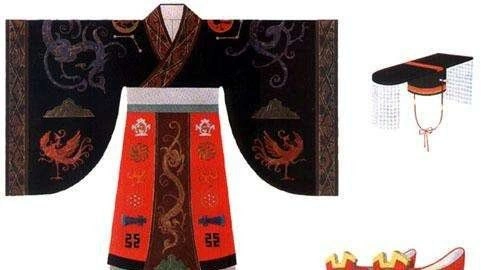

Ming women’s ceremonial attire was mainly daxiushan, paired with a special xiapei, named for its rainbow-like beauty. It was worn by palace noblewomen. Shaped like a long, colorful ribbon, it was draped around the neck and hung over the chest, with gold or jade pendants at the bottom, appearing tall and noble. Commoner women could wear it when marrying. “Hongshang xiapei, buyao crown, adorned with dianying and coral pendants,” wearing this wedding attire was the most beautiful moment in an ancient woman’s life.

The Ming also inherited the upper ru, lower qun women’s attire, developing into a winter garment called aoqun. Ao was the upper garment with gathered cuffs for warmth. Shang was typically plain qun, wide, with many styles like baizhe qun, fengwei qun, and yuehua qun.

Dignified, traditional, splendid, and vibrant, Ming attire had strict hierarchies and was a pinnacle of Chinese clothing art. But with the Qing’s shaving and attire change, it faded into history’s dust. “Clouds dream of attire, flowers dream of beauty; spring breeze brushes the railing, dew radiates splendor.” May Huaxia yiguan shine again with elegance.

Responses