7 Stunning Hanfu Hair Accessories: Celebrating Zan Zi’s Legacy

Hanfu hair accessories, particularly zan zi hairpins, are more than just adornments—they are vibrant threads in the tapestry of Chinese cultural heritage. These delicate creations, born from ancient ji (hairpin precursors), have adorned Chinese women’s hair for millennia, weaving stories of artistry, status, and tradition. As hanfu gains global popularity, zan zi hairpins captivate with their timeless elegance. This blog explores seven fascinating aspects of hanfu hair accessories, tracing their evolution and cultural significance to inspire your hanfu styling journey.

A Glittering Legacy: Zan Zi (Hairpins) Through the Ages

Zan zi (hairpins), a gem of Chinese culture, isn’t just a pretty accessory—it’s a witness to the evolution of hairstyles and aesthetics in ancient China. From pinning hair to stealing the show, zan zi (hairpins) transformed over centuries, blending utility with artistry. Each hairpin tells a tale of craftsmanship and beauty, forever tied to the women who wore them, crafting a dazzling narrative in Chinese fashion history.

Ancient Beginnings: The Dawn of Zan Zi (Hairpins)

The story of zan zi (hairpins) stretches back to the Neolithic Age, around 6,000–7,000 years ago. In the Yangshao culture archaeological sites, researchers uncovered bone ji (hairpin precursors) carved from animal bones. These simple tools pinned hair in place, laying the foundation for zan zi’s (hairpins’) future glory. As time flowed, zan zi (hairpins) spread across ancient China, evolving from practical pins to stunning decorations, leaving a bold mark on the canvas of Chinese aesthetics.

The story of hanfu hair accessories begins in the Neolithic Age, around 6,000–7,000 years ago. Archaeological finds from the Yangshao culture reveal bone ji, simple tools used to pin hair. These early zan zi hairpins laid the groundwork for a dazzling evolution. As noted in China’s National Museum, these humble pins transformed from functional tools into intricate works of art, reflecting the growing sophistication of Chinese cultural heritage.

Interested in the cultural and historical context of Hanfu and its accessories? Visit our comprehensive guide to explore the allure of Hanfu.

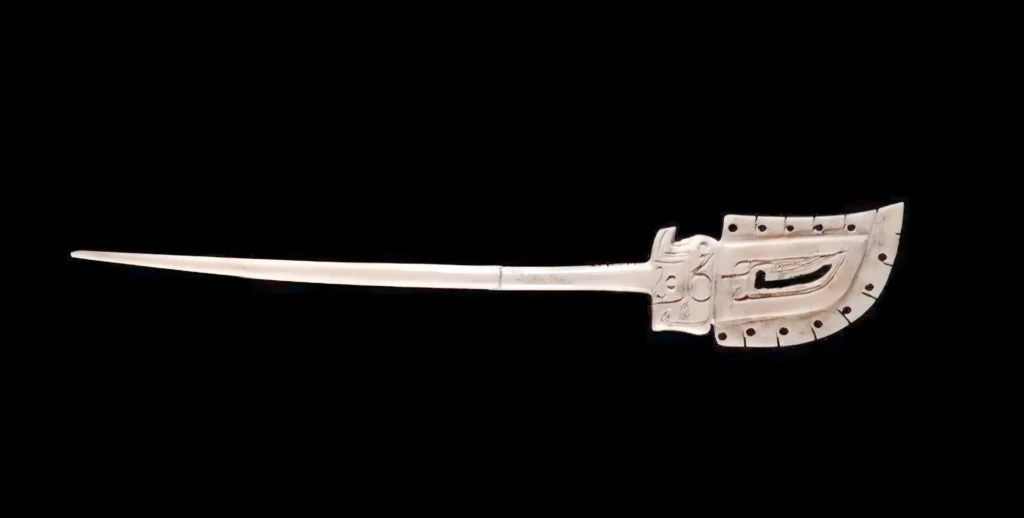

Shang Dynasty: Craftsmanship Takes Flight

By the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), zan zi (hairpins) stepped up its game. Used widely among commoners and elites, hairpins were crafted from bone and jade, with intricate carvings of birds and beasts showcasing artisans’ skill. No longer just tools, zan zi (hairpins) became art pieces, hinting at their wearer’s status and taste. This shift marked zan zi’s (hairpins’) rise as a symbol of beauty and identity in ancient China.

Dynasty-by-Dynasty Evolution: Zan Zi’s (Hairpins’) Stylish Journey

Zhou Dynasty: The Sacred Ji (Hairpin Precursor) Ceremony

In the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), the ji (hairpin precursor) took on a sacred role. When a girl turned 15, she celebrated her “coming-of-age” with the jili (hairpin ceremony), marking her transition to womanhood, much like a man’s capping ceremony. A finely crafted ji (hairpin precursor) was inserted into her hair, symbolizing maturity and cultural pride. This ritual gave zan zi (hairpins) a deeper meaning, tying it to Chinese values of growth and respect.When a girl turned 15, a finely crafted ji was placed in her hair to mark her coming-of-age, symbolizing maturity and respect for tradition. This ritual, detailed in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, tied zan zi hairpins to Chinese values, making them more than mere decorations.

Warring States: Luxury and Status

The Warring States period (475–221 BCE) brought luxury to zan zi (hairpins). Artisans poured their hearts into crafting hairpins from rare materials like white jade, carving intricate rope patterns or translucent designs. These exquisite pieces weren’t just accessories—they screamed nobility and power, reserved for the elite.

Qin and Han: A Burst of Diversity

In the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), hair accessories exploded with variety. The term ji (hairpin precursor) gave way to zan (hairpin), and new styles like buyao (dangling hairpins) and chai (hair forks) joined the party. Crafted from jade, gold, and even ivory, zan zi (hairpins) featured elaborate designs, from floral motifs to mythical creatures, reflecting Han’s vibrant culture.

Wei-Jin and Northern-Southern Dynasties: Big Hair, Bigger Zan (Hairpins)

The Wei-Jin and Northern-Southern Dynasties (220–589 CE) were all about drama. Women’s towering hairstyles needed serious support, so zan zi (hairpins) and chai (hair forks) multiplied, not just decorating but anchoring massive updos. These hairpins, often inlaid with pearls or carved with clouds, balanced beauty and function.

Tang Dynasty: A Golden Age of Glam

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) was zan zi’s (hairpins’) golden era. Both men and women wore long hair, with men favoring simple zan zi (hairpins) and women mixing zan (hairpins) and chai (hair forks) for flair. Tang jade zan zi (hairpins) blended foreign influences (think Persian curves) with Chinese artistry, carved with lotus flowers or dragons. The craftsmanship was next-level, making every hairpin a tiny masterpiece.

Song Dynasty: Delicate and Diverse

In the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), zan zi (hairpins) embraced elegance. Focusing on the hairpin’s head, artisans mastered openwork and filigree techniques, crafting flowers, birds, mandarin ducks, or dragon-phoenix patterns. Three-dimensional animal zan zi (hairpins), like tiny jade cranes, added a playful twist, bringing fresh energy to Song’s refined aesthetic.

Yuan Dynasty: Bold and Sculptural

The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE) took zan zi (hairpins) to new heights. Building on Song’s finesse, artisans perfected openwork carving, creating almost 3D effects. Using “deep knife” techniques, they sculpted lifelike designs—think tigers or mythical chi (dragon-like) dragons—that popped with立体感. Yuan zan zi (hairpins) were bold yet intricate, reflecting the era’s dynamic spirit.

Ming Dynasty: Craftsmanship at Its Peak

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) was a zan zi (hairpins) masterpiece factory. Techniques like welding, filigree, and inlay created jaw-dropping hairpins. The leisi jinfeng zan (gold filigree phoenix hairpin) stole the show, with delicate gold threads shaped into phoenixes, studded with gems. Less flashy than Tang but endlessly varied, Ming zan zi (hairpins) were pure artistry.

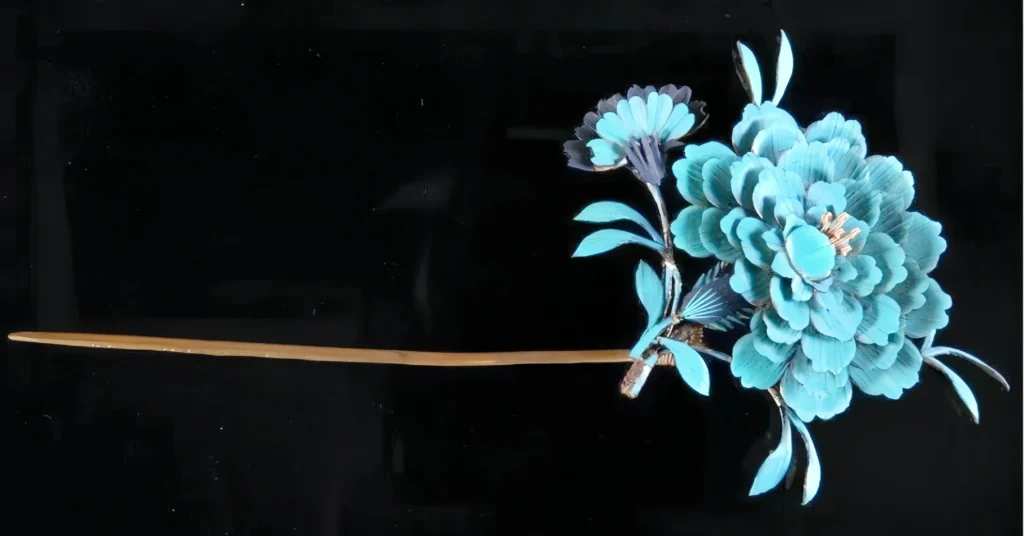

Qing Dynasty: Women’s Exclusive Elegance

In the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 CE), as Manchu men adopted shaved hairstyles, zan zi (hairpins) became a women-only accessory. Craftsmanship reached new finesse, with hairpins inlaid with kingfisher feathers, pearls, or intricate enamels. Qing zan zi (hairpins), preserved in the Palace Museum, reflect societal shifts and timeless beauty in every curve.

The Soul of Zan Zi (Hairpins): More Than Just Decoration

Zan zi (hairpins) weren’t mere trinkets—they held power. In ancient China, a hairpin symbolized dignity and status. Criminals were barred from wearing them, and even empresses, if punished, had their zan zi (hairpins) removed as a mark of shame. Some legends whisper of zan zi (hairpins) swaying kings’ decisions or sparking historical turning points—a tiny pin with mighty influence!

From the bone ji (hairpin precursor) of the Neolithic to the gold phoenixes of the Ming, zan zi (hairpins) carried the dreams and artistry of Chinese women. They adorned cloud-like updos, framed delicate faces, and whispered tales of love, power, and legacy. Today, as hanfu lovers pin modern zan zi (hairpins) into their hair, they’re not just styling—they’re reviving a cultural symphony that’s echoed for thousands of years.

Tips for Incorporating Zan Zi in Modern Hanfu Styling

To embrace hanfu hair accessories in your hanfu styling, consider these tips:

- Choose Authentic Designs: Opt for zan zi hairpins inspired by Tang or Ming styles for cultural accuracy.

- Match with Hanfu: Pair hairpins with appropriate hanfu styles, like Song-style ruqun, for a cohesive look.

- Learn the Context: Study the cultural significance of designs, such as phoenix motifs for auspiciousness.

- Support Artisans: Purchase from reputable sellers, like those on hanfu accessory shops, to ensure quality and authenticity.

Zan zi are not only beautiful but also showcase remarkable craftsmanship. Want to learn more about the materials and techniques behind Hanfu hair accessories? Check out this detailed exploration of tradition and modernity.

Responses