How Did Ancient Chinese Repel Mosquitoes?

As summer fades, ancient Chinese mosquito repellent methods remain relevant, tackling the persistent annoyance of mosquitoes. The saying “autumn mosquitoes are fierce as tigers” highlights their tenacity. Ancient Chinese faced these pests too, as Jin Dynasty scholar Fu Xuan vented in his Ode to Mosquitoes: “Swarming in countless numbers, their buzzing forms a thunderous roar, inflicting cruel venom on the living.” This article explores how ancient Chinese used mosquito nets, smoke fumigation, mosquito coils, and fragrance sachets to combat mosquitoes with ingenuity.

With changing times and advancing technology, modern people have mosquito coils, floral water, repellents, and wristbands to fend off mosquitoes. So, how did ancient Chinese tackle these buzzing pests?

Mosquito Nets: Ancient Chinese Mosquito Repellent Barriers

To stop mosquito bites, the clever ancient Chinese invented mosquito nets. Their advanced textile techniques provided a solid foundation for building physical barriers against mosquito attacks.

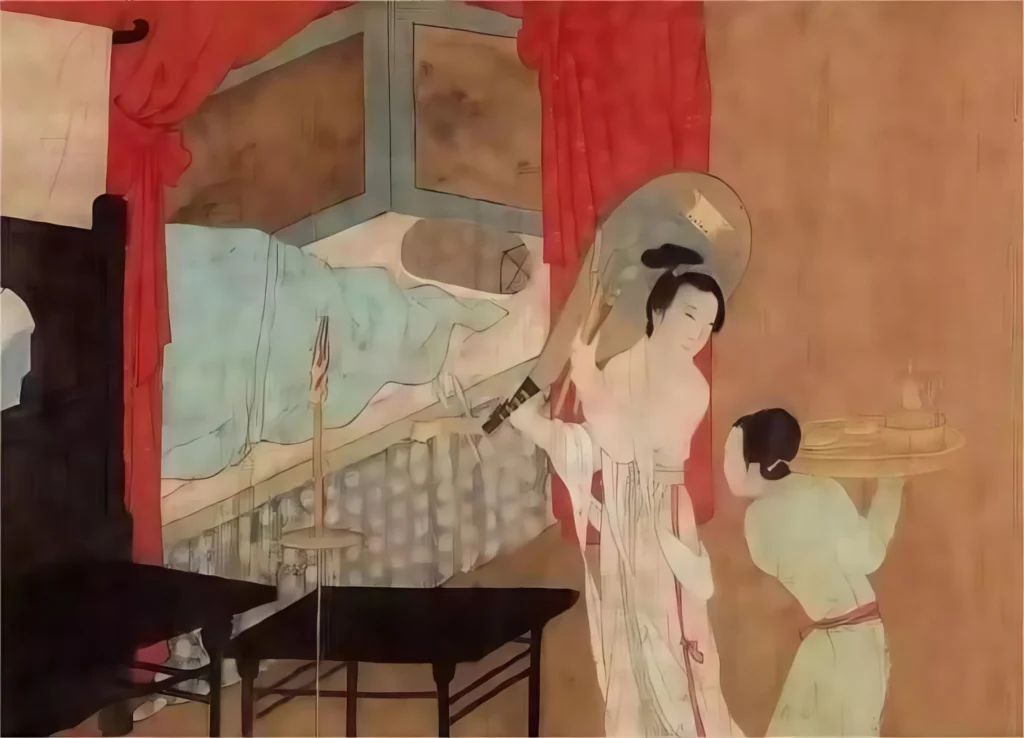

As early as the Spring and Autumn period, Duke Huan of Qi used a “green gauze canopy” to ward off mosquitoes. Wealthy families paired nets with colorful fabrics, decorative trims, and intricate patterns to showcase status. The Han Dynasty poem Peacock Flies Southeast describes: “A red silk canopy with fragrance sachets hanging at four corners.” Such fancy “mosquito nets” were a luxury for nobles.

The Book of Songs (Shijing), in the Xiaoxing poem, mentions: “Marching at night, clutching quilts and a chou (mosquito net).” Nets needed to be breathable yet tightly woven to keep mosquitoes out, making high-quality fabric costly. Until the late Qing Dynasty, mosquito nets weren’t something every household could afford.

Smoke Fumigation

For common folks who couldn’t afford nets, a cheaper mosquito-repelling trick was smoke fumigation. In the Western Zhou Dynasty, special “insect-repelling officers” called Jianshi were appointed. While their daily tasks often involved prayers and rituals, they also burned a plant called mangcao (ratbane grass) to drive away mosquitoes. This grass was so potent it could allegedly poison rats. By the Han Dynasty, true incense burning emerged with the invention of censers. Historical records note that burning “moon-arrival incense” was used to “ward off plagues.” Incense evolved from a spiritual tool to a practical one, with materials expanding to include mosquito-repelling properties.

Fire Ropes

The strong fumes of mangcao weren’t ideal for enclosed rooms, so people discovered milder alternatives like mugwort (aicao) and wormwood (hao). These produced less smoke and had a gentler scent, perfect for household use. From this, the earliest mosquito-repelling tool was born: fire ropes. Made by twisting mugwort or wormwood into rope-like strands, these were lit at bedtime, their aroma keeping mosquitoes at bay. This was the precursor to modern mosquito coils.

Ming Dynasty scholar Fang Xiaoru’s Dialogue with Mosquitoes describes such a scene: “A boy gathers wormwood, ties it into a bundle, and lights the end. The thick smoke swirls left and right, circling the bed several times, driving mosquitoes out the door.”

Mosquito Coils

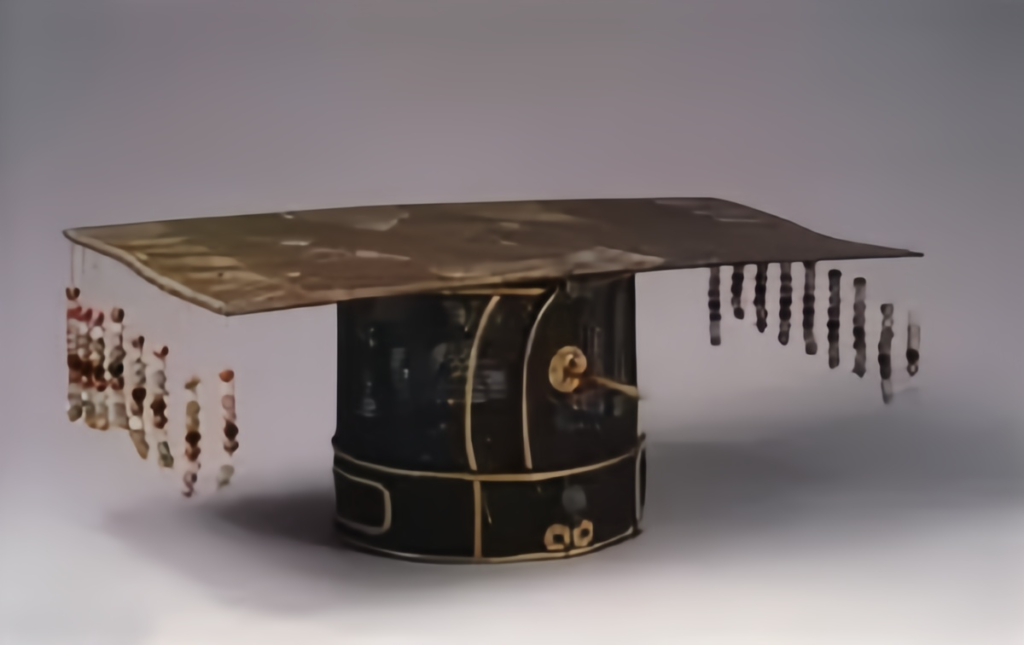

By the Song Dynasty, specialized “mosquito coils” existed. The Song-era notebook Gewu Cutan records: “At the Dragon Boat Festival, gather duckweed, dry it in the shade, add realgar, wrap it in paper to make incense sticks, and burn them to repel mosquitoes.” These early coils were stick-shaped with a core.

By the Qing Dynasty, mosquito coil craftsmanship was highly refined. A late-Qing British traveler, in his book Living Among the Chinese, described buying tea seeds in Fujian’s Wuyi Mountains. Tormented by mosquitoes in the humid heat, his local guide bought mosquito coils, solving the problem. Impressed, the Briton brought these coils to Europe, sparking curiosity among European entomologists and chemists eager to study the Chinese “rustic mosquito incense.” By the Qing Dynasty, coils were refined, impressing a British traveler in Fujian, as noted in Living Among the Chinese. Learn about Qing Dynasty innovations at Smithsonian.

Fragrance Sachets

The above methods worked at home, but outdoors, mosquitoes still attacked. Enter the fragrance sachet—portable and stylish. Qin Guan’s poem Mantingfang evokes: “Fragrance sachet softly undone, silk sash lightly parted,” hinting at a beauty’s scent wafting near. Sachets were simple to make: sew a small pouch and fill it with mosquito-repelling herbs like agastache, mint, star anise, fennel, or mugwort. Beyond gifting them as tokens of affection, sachets served practical purposes—repelling mosquitoes and preventing disease—blending function with beauty.

Conclusion

Don’t ancient Chinese mosquito-repelling methods hold up well against modern tech? They showcase clever wisdom, eco-friendly practices, and a touch of charm. From nets to sachets, these solutions reflect a blend of practicality and cultural flair.

Responses