Ancient Hairstyles of Chinese Women

(An Overview of Ancient Chinese Hairstyles and Traditional Chinese Hair Buns)

Ancient Chinese women hairstyles reflect social status, age, and aesthetic ideals across dynasties. From simple girlhood styles to elaborate ceremonial forms, Chinese women hairstyles evolved alongside ritual systems, craftsmanship, and cultural values. Among them, traditional Chinese hair buns played a central role, serving both functional and symbolic purposes.

Chuíhuán Fenxiao Hairstyle

Chuíhuán Fenxiao was a hairstyle commonly worn by unmarried young girls and is one of the most representative Chinese women hairstyles associated with maidenhood. The hair was divided into sections, tied into loops on the top of the head without support, allowing them to hang naturally. The ends were bound into narrow tails that draped over the shoulders, also known as the “swallow-tail” style.

According to Guoxian Jiayou, “Emperor Ming of Han ordered palace women to wear the Hundred-Flower Fenxiao hairstyle.” During the Tang dynasty, this hairstyle often served as a visual marker of youth and purity and is frequently cited when discussing early traditional Chinese hair buns for young girls.

Double-Level Bun (Shuangping Ji)

The double-level bun is created by dividing the hair evenly into two large sections and shaping them into symmetrical buns or loops that hang on both sides of the head. This hairstyle was commonly worn by palace attendants, maids, or underage girls, making it a typical example among everyday Chinese women hairstyles.

Records show it first appeared during the Qin dynasty and continued into modern times. The most typical forms are the double-yazi bun and double-hanging bun, both belonging to the broader category of traditional Chinese hair buns. This style appears frequently in surviving ancient paintings, such as the attendants in the Dunhuang Mogao Cave donor murals and Yan Liben’s Scroll of Emperors.

Lily Bun (Baihe Ji)

The lily bun is styled by cleaning and dividing the hair into sections, then coiling and stacking them neatly on top of the head. The result is a full, layered bun resembling a blooming lily, creating an elegant and grand appearance. This hairstyle is often referenced in studies of formal traditional Chinese hair buns favored by noblewomen.

Lingyun Bun

The Lingyun bun is a tall, single-loop hairstyle. According to Annotations on Ancient and Modern China, “Qin Shi Huang ordered the empress to wear the Lingyun bun; the three consorts wore the Wangxian nine-loop bun, and the nine ladies wore the Canluan bun.” These were all classified as high-loop hairstyles, a distinctive subgroup within ceremonial Chinese women hairstyles.

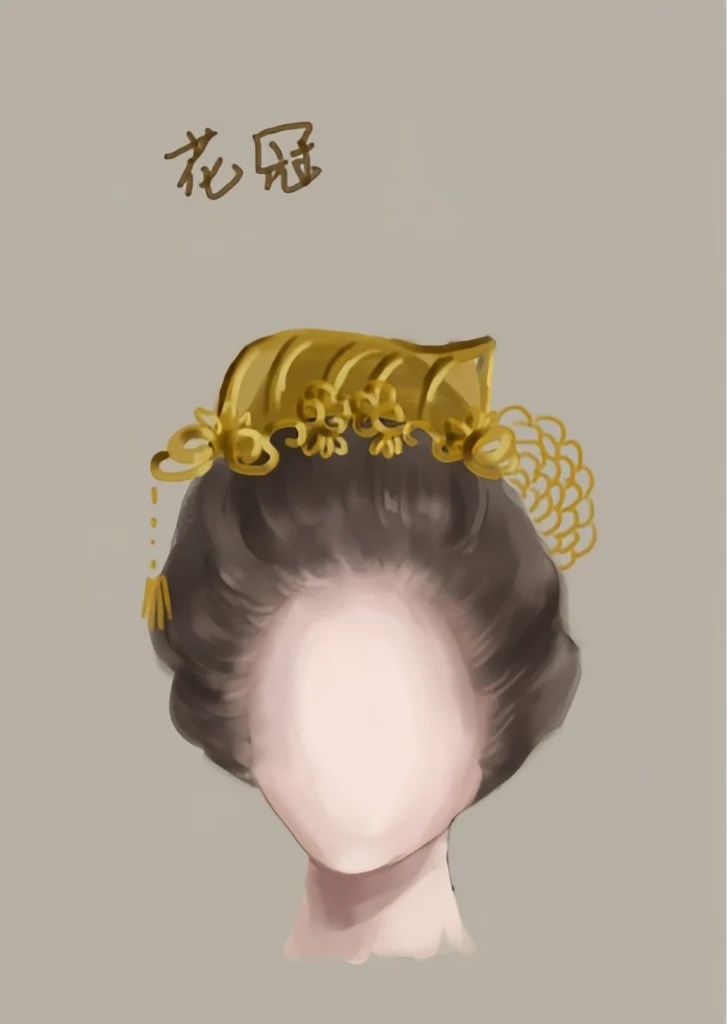

Phoenix Crown (Fengguan)

The phoenix crown was a ceremonial headdress worn by empresses and titled noblewomen in ancient China. Decorated with phoenix motifs, pearls, jade, and kingfisher feathers, it was worn mainly during major rituals and formal occasions. Although not a bun itself, it was often paired with structured traditional Chinese hair buns to provide stability and visual balance.

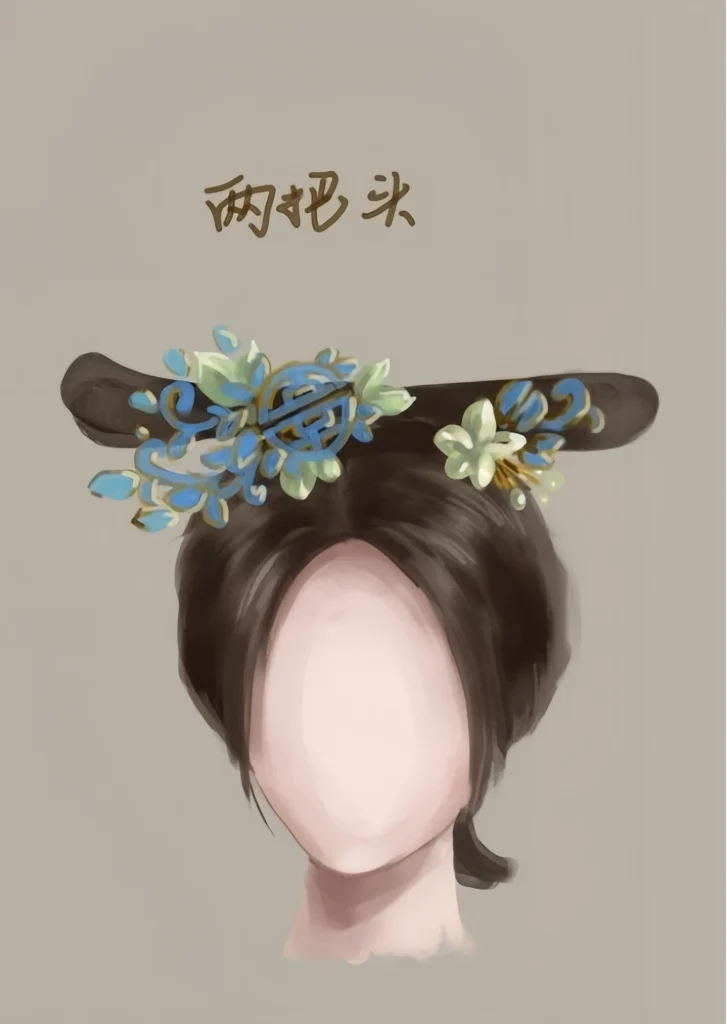

Manchu Hairstyles of the Qing Dynasty

Elite women of the Qing dynasty maintained a dominant hairstyle tradition for a long period. In the early Qing, the crown and clothing system became standardized. Except for major ceremonies when empresses wore court crowns, they wore dianzi headpieces during festive occasions.

However, wearing a dianzi made it impractical to leave braided hair hanging at the back, so women adopted two horizontal buns shaped like small side knots. This style held the headpiece securely and was known within the palace as the “small liangbatou,” becoming one of the most recognizable Chinese women hairstyles of the Qing court.

Evolution of Hair Accessories in the Mid-Qing Period

The mid-Qing era, often referred to as the Qianlong Golden Age, saw major developments in lifestyle and craftsmanship, including jewelry-making. As valuable ornaments from across the empire flowed into the palace, court women increasingly sought elaborate hair decorations. However, the small liangbatou proved inadequate—it hung too low, loosened easily, and could not support heavy jewelry.

To solve this, a new styling tool called the hair frame was invented. Made of wood or twisted metal wire, it resembled a horizontal eyeglass frame. During styling, the base was secured first, then the frame placed on top. Hair was divided into two sections, crossed and wrapped around the frame, with a long flat hairpin inserted horizontally through the frame holes. Loose strands were fixed with pins, allowing even heavy ornaments to stay in place. The side hair near the ears was flattened, tied with ribbons, and slightly curved upward like a swallow’s tail, giving the entire hairstyle the look of a bird ready to take flight.

Age-Based Hairstyles in the Qing Court

Qing palace women adjusted hairstyles and accessories according to age. Younger women wore bright, colorful jewelry to express youthful vitality, while older women favored refined, high-quality ornaments that conveyed dignity and composure.

Royal women wearing liangbatou hairstyles often paired them with high-platform shoes, resulting in an upright posture and restrained movement. This visual harmony between posture and Chinese women hairstyles became an idealized standard of female comportment.

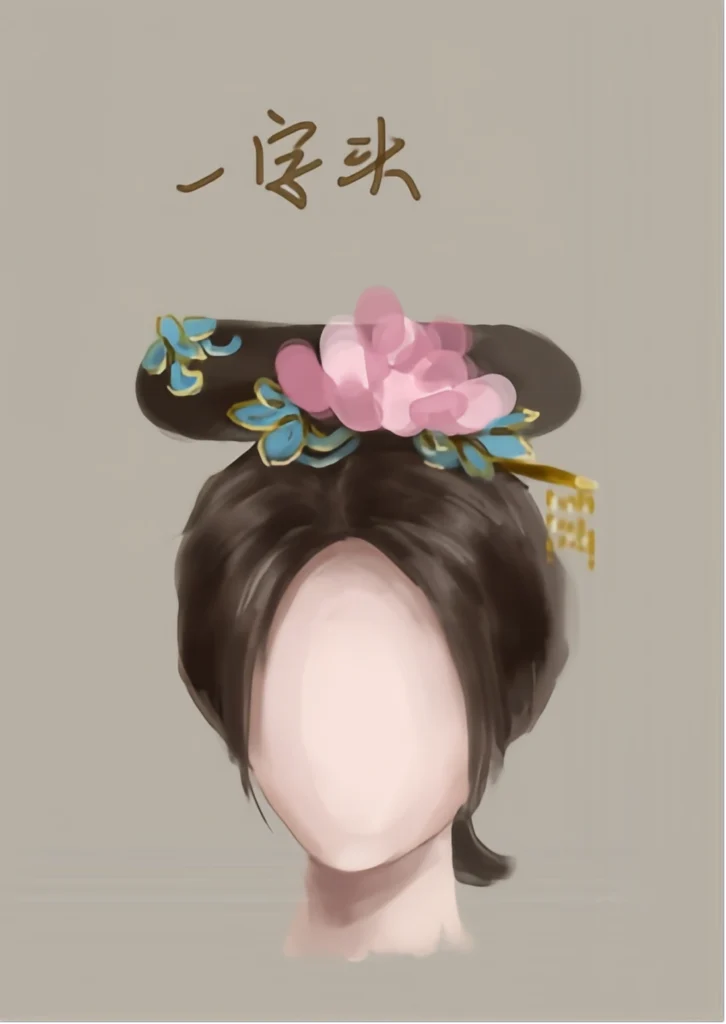

The Emergence of the Dala Chi

In the late Qing dynasty, the dala chi hairstyle emerged. It was a rigid, fan-shaped structure about one chi high, with an internal metal frame wrapped in fabric and covered with dark satin. Worn as a detachable decorative piece, it could be easily put on or removed. Invented under Empress Dowager Cixi’s influence, the dala chi reshaped contemporary beauty standards. As it gained popularity, the traditional liangbatou gradually faded from use.

Paojia Bun (Late Tang Period)

In the late Tang dynasty, women in the capital styled their hair by framing the face with side hair and adding a cone-shaped bun on top, known as the Paojia bun, also called pengbin or phoenix head. This hairstyle is described in New Book of Tang · Five Elements Treatise and Zhuangtai Ji. It features side hair hugging the face and an added topknot, often a hairpiece. This style survives today in Chinese opera dan roles.

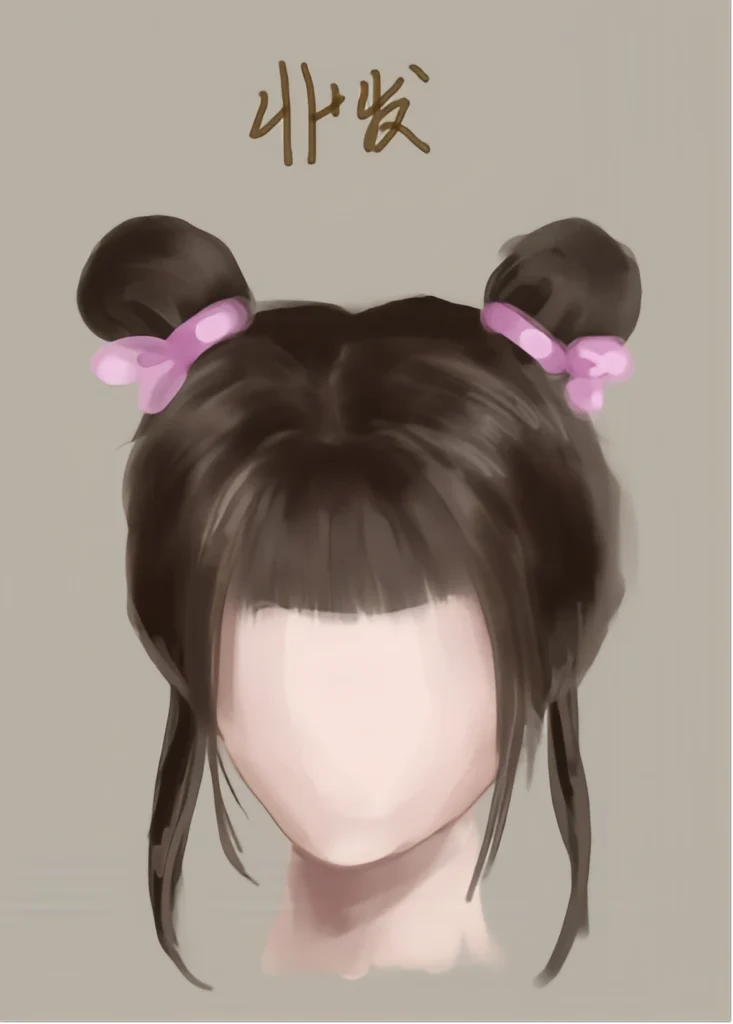

Double-Yazi Bun

The double-yazi bun is the most common variation of the hanging-bun style. Hair is divided evenly and tied into buns placed on both sides of the head. Forehead hair is often left hanging as bangs, commonly worn by maids, and is frequently cited in visual studies of traditional Chinese hair buns in daily life.

Guan Hairstyle (Children and Unmarried Girls)

The guan hairstyle was worn by children or unmarried girls. Hair was divided into two sections and tied into cone-shaped buns on both sides of the head, reinforcing age-based distinctions within Chinese women hairstyles.

Small Crown Hairstyle

This style features a tightly bound bun topped with floral decorations and was especially popular among Ming dynasty women. It represents a refined branch of traditional Chinese hair buns emphasizing balance and ornamentation.

Flying Immortal Bun (Feixian Ji)

The flying immortal bun features high loops on both sides of the head. Often associated with celestial imagery, it occupies a unique symbolic position in the history of Chinese women hairstyles, especially for unmarried women.

Fallen Horse Bun (Duoma Ji)

The fallen horse bun gathers hair into a large cone tied with silk cord, drooping to one side or the back of the head. Historical records describe it as soft and delicate in appearance, often used to convey a gentle, fragile image.

Straight-Line Hairstyle (Yizitou)

Luxurious and tall, resembling a ceremonial archway, this hairstyle is closely related to the dala chi but without a crown component, further expanding the architectural diversity of Chinese women hairstyles.

Double-Blade

Bun Hair is gathered upward and twisted into two upward-curving shapes resembling blades. Texts from the Tang dynasty describe similar reversed-coil styles decorated with colorful flowers.

Tilted Bun (Qing Ji)

This style tilts the bun toward the front or side of the head and appears frequently in paintings of court ladies. According to the Book of Jin, it was a popular fashion among noblewomen during the Taiyuan era.

Ingot Bun (Yuanbao Ji)

Hair is gathered on top and shaped over a wooden or artificial base to resemble a gold ingot. Historical records note that such false hairpieces were used when natural hair was insufficient. Similar styles appear in Tang dynasty tomb figurines.

Flying Apsara Bun (Feitian Ji)

The flying apsara bun features three loops rising straight upward from the crown. According to Song Dynasty Five Elements Records, women divided their hair into three parts and lifted the loops vertically, calling it the flying apsara style. Ancient “Hundred-Flower” hairstyles also belong to this category.

Want to explore more about Hanfu Hairstyles?

Check our Hanfu Hairstyles Guide for authentic tips!

Responses