Ancient Chinese Armor: Military Dress and Uniforms Through the Dynasties

Ancient Chinese Armor Through the Dynasties

Shang Dynasty (c. 17th–11th century BCE)

Starting from late primitive society, as tribes kept conquering each other, wars became more frequent and bigger. Armies could reach 13,000 men at times—huge forces made up of multiple units. Without some kind of uniform clothing, coordinating everyone on the battlefield would’ve been a nightmare. So that’s when ancient Chinese military clothing really started to take shape, laying early foundations for Chinese military armor by dynasty in ancient Chinese armor history and Hanfu armor history.

Western Zhou (11th century BCE – 771 BCE)

By the late 11th century BCE, King Wu of Zhou crushed the Shang army led by King Zhou of Shang and founded the Western Zhou dynasty. This was the heyday of bronze casting, and armor began shifting toward metal materials. Early Western Zhou introduced the “guoren” (urban citizens) conscription system. The Rites of Zhou (Spring Offices – Minister of Clothing) records in detail the ceremonial robes of the Zhou king and feudal lords, including the “weibian” robe specifically for military campaigns. There were no dedicated military officers yet—the king and lords themselves commanded the troops. Their “weibian” robe served as the dedicated battle dress.

The only difference between commanders and regular soldiers was that soldiers’ lower robes were shorter (easier to run in), simpler, and made from coarser fabric. The “lian jia” (padded armor) worn by Zhou warriors was usually made of layered silk or hemp stuffed with thick cotton—basically a type of fabric armor in this early stage of ancient Chinese armor and ancient Chinese military clothing.

Eastern Zhou (Spring and Autumn & Warring States, 770–221 BCE)

In 770 BCE, power struggles over the Zhou throne led to rebellion. Lords allied with the Quanrong nomads, stormed the capital Haojing (modern Xi’an), killed King You, and ended Western Zhou. The new king, Ping, moved the capital to Luoyi (modern Luoyang). This kicked off the Eastern Zhou era—also called Spring and Autumn and Warring States.

It was a long period of endless lord-vs-lord fighting, the full transition from slave society to feudal society, and massive leaps in military manufacturing tech. Armor workshops ran almost like modern assembly lines and reached impressive scale. Besides widespread leather armor, bronze armor was common. By late Warring States, iron armor appeared. Deep robes (shenyi—upper and lower garment sewn together) became standard military wear.

As cavalry units emerged in many Yellow River states, clothing had to adapt—leading to the adoption of tight, narrow-sleeved jackets, trousers, and leather boots (the so-called “Hu clothing” style from northern nomads). Warring States leather armor was often made from rhino or shark skin, painted with colors; it included a body piece, sleeves, and a skirt. Scales overlapped left-over-right horizontally and bottom-over-top vertically. Helmets were assembled from 18 pieces. Iron armor emerged mid-Warring States, evolving from simpler bronze “beast-face” chest plates. Typical iron armor used fish-scale or willow-leaf shaped plates laced together. This era shows clear progression in ancient Chinese military clothing, ancient Chinese armor, and Chinese military armor by dynasty.

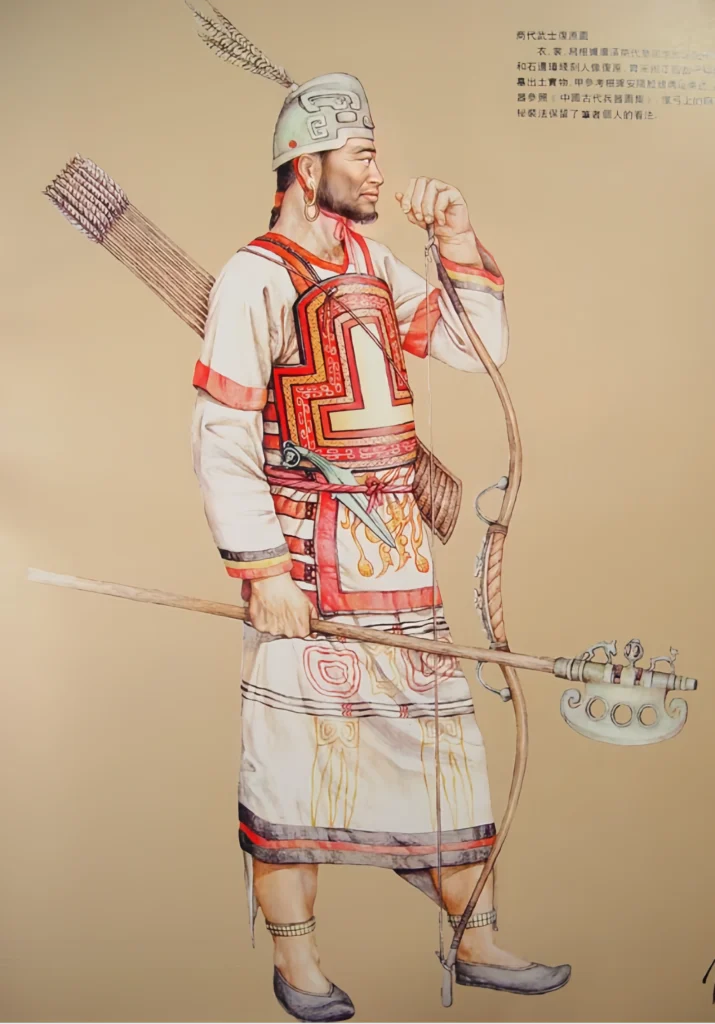

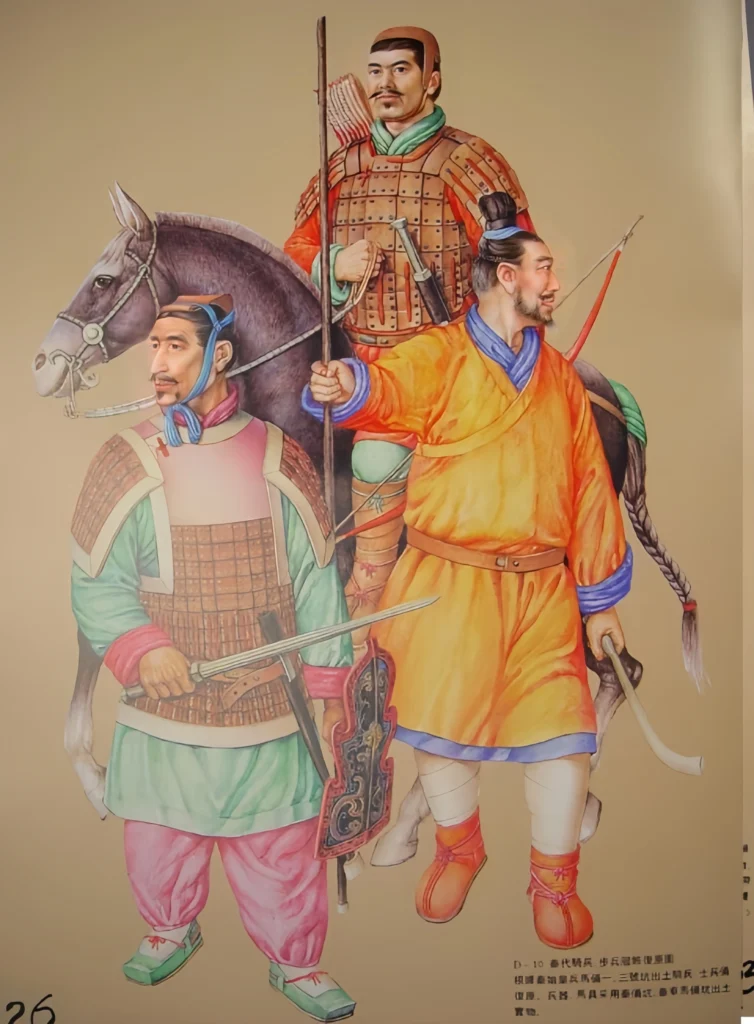

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE)

Qin was ancient China’s first true military superpower. Thanks to the discovery of the Terracotta Army in the First Emperor’s mausoleum, we have the most complete, accurate, and detailed record of any dynasty’s military uniforms and armor.

From generals down to ordinary soldiers, everyone wore basically the same style: a deep robe on top, narrow trousers below, leg wraps (xingchan) for foot soldiers, and boots or shoes. Headgear fell into four main types: 1) two kinds of “ze” cloth caps (one for cavalry, one for officers); 2) cavalry helmets; 3) various hats; 4) topknots. Footwear included four styles—high boots, square-toe upturned shoes, square-toe flat shoes, and square-toe pointed shoes—all tied with straps over the instep and ankle. Everyone cinched the waist with a leather belt fastened by a hook.

The armor shown here was for frontline commanders. Chest and back had no scales—instead painted geometric colorful patterns, probably on stiff brocade or painted leather. The armor shape had a pointed front hem and straight back hem, wide borders, and more geometric designs. Small scales covered the lower chest, mid-back, and waist—160 square plates total, each about several centimeters per side. Plates were laced with leather thongs or sinew in V-shapes and riveted. Shoulders had leather-like shoulder guards (pibo), with colorful ribbon knots visible at chest, back, and shoulders. This iconic Qin setup remains a cornerstone in ancient Chinese armor, ancient Chinese military clothing, and Chinese military armor by dynasty.

Qin Soldier Armor Reconstruction

This is the most common style seen on the terracotta warriors—standard infantry gear. Key features: chest scales overlap top-over-bottom, abdomen scales bottom-over-top (for better movement). From the center line, scales overlap outward to both sides. Shoulder scales match the abdomen pattern. Scales around shoulders, abdomen, and neck are linked by connecting straps. Each scale has 2–6 rivets (rarely more). Armor length front and back is equal (about 64 cm), hem usually rounded without extra edging.

Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

Han is divided into Western (Former) and Eastern (Later) periods by Wang Mang’s brief Xin dynasty. Early Western Han military attire largely followed Qin patterns. By Western Han, iron weapons dominated thanks to developments from late Warring States and Qin. All Han armor was forged iron.

Overall, Han uniforms resembled Qin’s a lot—everyone, high or low rank, wore a single-layer deep robe (chan yi, sometimes called crepe single robe) on top and trousers below. Headgear was usually a flat cloth cap (pingjin ze) covered by a military cap; Eastern Han officers sometimes added a gauze cap on top. Soldiers wore two belts—one leather, one silk. Footwear leaned toward shoes (more than boots), with round flat soles or crescent-toe styles.

Han marks the real beginning of a formal military officer system. As armies grew huge and tactics got complex after Spring and Autumn, dedicated military specialists appeared. Rank wasn’t shown only by clothing—uniform badges mattered too (a system that already existed pre-Qin). Han badges included: zhang (low-rank tags for soldiers, usually listing name, unit, and identity for corpse identification); fan (shoulder-slung silk scarves for officers); and feather attachments (used by both officers and men). Cavalry advanced dramatically in late Han thanks to the saddle and stirrup. This era’s Hanfu military dress blended ceremonial and practical elements seamlessly in Hanfu armor history and ancient Chinese armor.

Western Han Cavalryman with Iron Halberd Reconstruction

Iron armor became widespread in Western Han and eventually the main type—called “mysterious armor” (xuan jia) back then. Han uniforms shared many similarities with Qin’s—everyone wore chan yi robes and trousers. Robes were deep-style. Common military colors were red tones like crimson and deep red.

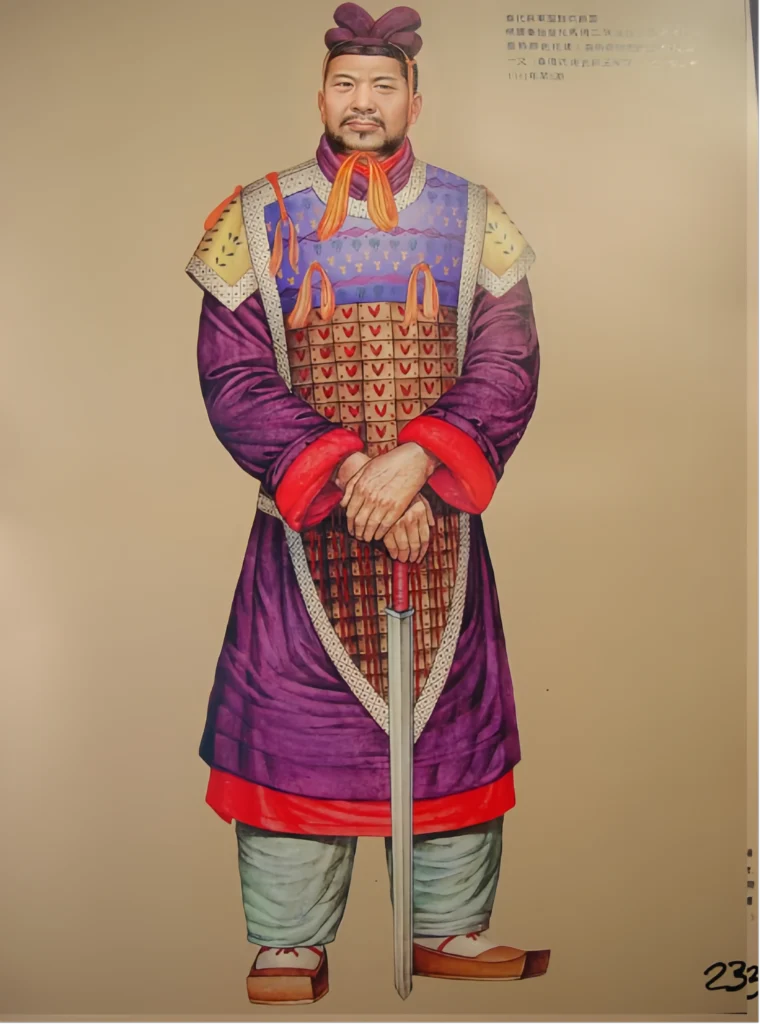

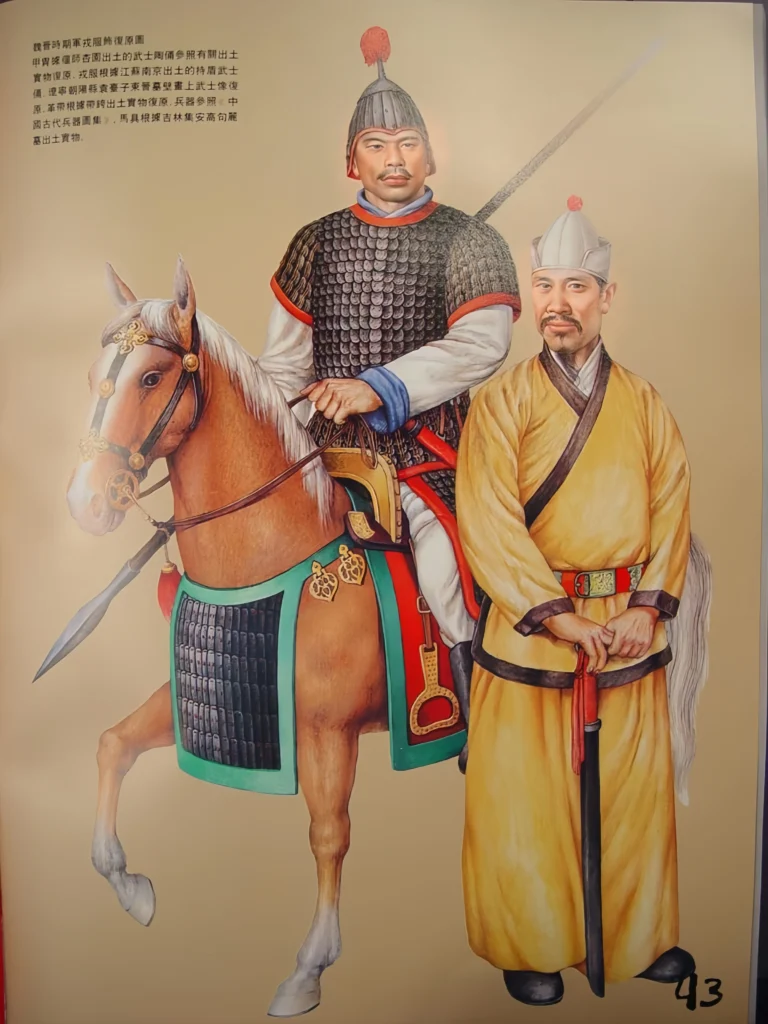

Wei, Jin, and the Sixteen Kingdoms (220–420 CE)

The brutal power struggles at the end of Eastern Han exploded into full-scale civil war. After years of fighting and consolidation, the Sima family wiped out Wu, reunified the country, and founded the Jin dynasty (Western Jin). But under Emperor Hui, the “War of the Eight Princes” tore everything apart again, leading to the chaotic Eastern Jin + Sixteen Kingdoms period. Constant warfare pushed tactics forward, but wrecked the economy so badly that weapons and armor didn’t see major leaps compared to Han times.

The typical military outfit in this era shifted to battle robes (zhanpao) and the “kuzhe” suit (short jacket + trousers). Robes reached below the knee with wide sleeves. Kuzhe jackets were short (down to the hips), tight-fitting, narrow-sleeved. Both usually had crossover straight collars, though round collars appeared too. Trousers were wide-legged; Eastern Jin styles had especially huge pant legs, almost like modern skirt-pants. Headgear included military caps (wuguan), pheasant-feather caps (heguan), “quedi” caps, “Fan Kuai” caps, cloth wraps (ze), headbands, and simple skullcaps (qia). Soldiers mostly wore round-toe boots without upturned tips. Armor and outer robes were always belted.

One common armor was the tube-sleeve iron scale armor: chest and back connected, short sleeves, fish-scale plates, pulled on over the head. It looked a lot like Western Han iron armor and was extremely tough. Helmets mostly followed Eastern Han shapes, often topped with tall feather plumes. Typical Wei-Jin outfit on the right: robe reaching below the knee, wide sleeves; short tight kuzhe jacket with narrow sleeves; crossover right-front collar (though round-neck versions existed too). Ancient Chinese military clothing continued evolving here in ancient Chinese armor traditions and Hanfu armor history.

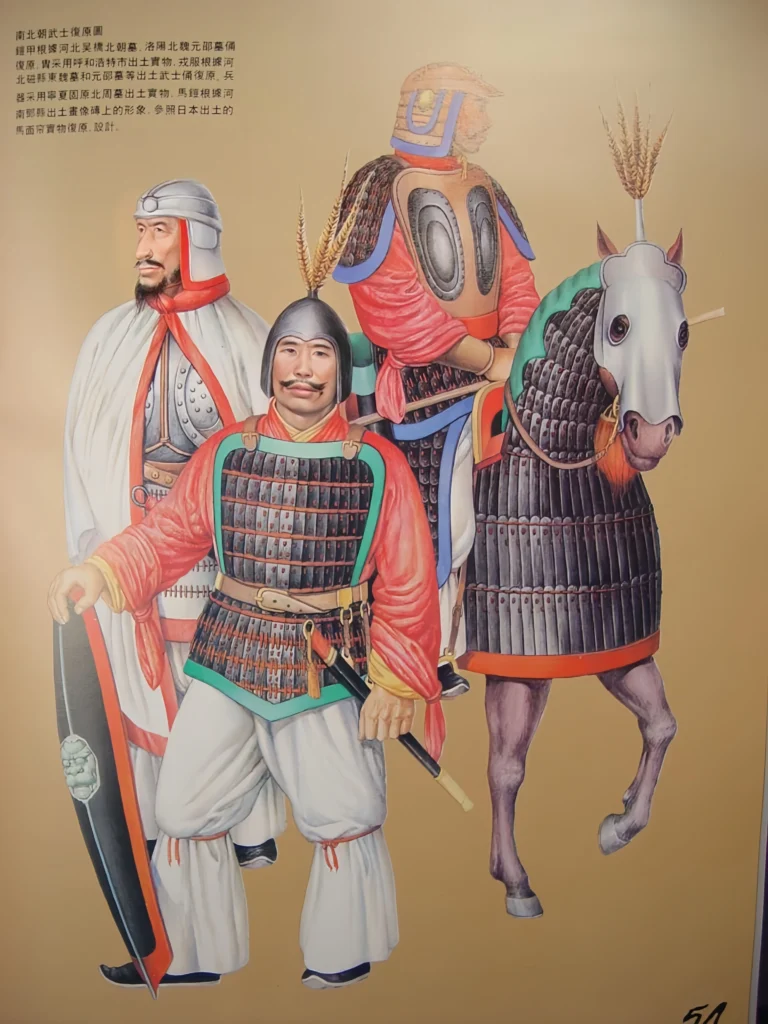

Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589 CE)

This was a golden age for weapons and armor production—more types, better quality, and advanced techniques. The most iconic armor was the “liangdang” (double-shouldered) style: one plate covering the chest, one the back. Head protection included doumou helmets, various zhou (helmets), and full helmets.

Many rulers during this time were from northern nomadic groups (Xiongnu, Jie, etc.), so their armies brought steppe clothing influences into the Central Plains. Military attire became super diverse, blending multiple ethnic styles, and clearer distinctions appeared between officers and regular troops thanks to a more mature officer system.

The most striking garment was the “liangdang shan” — a jacket that mimicked the shape of liangdang armor but made of cloth or leather, worn by officers as formal duty wear (this style lasted into Tang). Short-sleeve ru jackets were also common: narrow cuffs, front opening, big lapels, available in single or padded versions. Trousers mostly carried over the Eastern Jin wide-leg style, often tied below the knee with cords. Headgear: flat cloth caps and various hats were standard.

Front row in reconstructions: liangdang armor reaching above the knee; upper body either small linked scales or large solid plates; chest/back pieces connected at shoulders and sides with straps. Back row: mingguang armor (“bright-shining armor”). Named for the large round chest and back protectors (usually polished bronze or iron) that gleamed like mirrors in sunlight. Some versions just added two round plates to a basic liangdang base; fancier ones included shoulder guards, knee guards, and multiple layered shoulder pieces. Body armor usually reached the hips, cinched with a belt.

(Note: the idea that mingguang’s “heart mirrors” came from Han “sunlight mirrors” is a popular theory but not really supported.) This period highlights key evolutions in Hanfu armor history, Hanfu military dress, and ancient Chinese armor.

Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE)

Sui was another short-lived but unifying dynasty after Qin. Because it didn’t last long enough to finish big reforms, most institutions—including military dress—largely carried over from Northern and Southern Dynasties.

Most common armors: improved liangdang and mingguang. Liangdang got upgrades: body mostly small fish-scale plates, now extending down to the abdomen (replacing earlier leather skirts). Lower hem used crescent or lotus-petal shaped plates to better protect the groin. These changes seriously boosted lower-body defense. Mingguang stayed mostly the same as Northern/Southern styles, just with longer leg skirts. Everyday military wear: round-collar long robes.

Reconstructions usually show a warrior in plain robe on one side, armored on the other. Chinese military armor by dynasty sees continuity here in ancient Chinese armor and ancient Chinese military clothing.

Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE)

Tang was the absolute peak of feudal China—its politics, economy, and culture influenced everything that came after.

This was when the military officer system fully matured, so Tang military dress is the most complete and systematized of any dynasty. Officers had court dress and everyday dress; both were for ninth-rank and above civil/military officials. Dedicated battle wear for officers was the “quekua shan” (split-side shirt) often embroidered with patterns. Regular soldiers wore two main styles: round-collar narrow robes or quekua robes (theirs plain, no embroidery). Headgear was the “zhe shang jin” (folded-head cloth), later called futou—by late Tang it became a ready-to-wear cap needing no tying. Many Tang soldiers wrapped a red or white gauze scarf around the futou.

Early Tang armor and uniforms still followed late Northern/Southern → Sui styles. After Emperor Taizong’s Zhenguan era, major clothing reforms created a distinct Tang look. By Gaozong and Wu Zetian’s reigns, the empire was rich and peaceful; luxury crept in, and much of the armor/uniforms became decorative show pieces rather than practical gear. After the An-Shi Rebellion, things swung back toward functional combat designs. Late Tang armor settled into fixed forms.

The Tang Liudian lists thirteen types: mingguang, guangyao, xisuo (chain mail), shanwen, niaochui, xilin (iron types named for plate shape); plus pi jia (leather), mu jia (wood), baibu (white cloth), zaojuan, bubai (fabric types). Mingguang remained the most common. New garments appeared too, like the “duanhou yi” (short-back coat). Late Tang also introduced “baodu” — a half-round padded waist wrap to stop weapons and armor from clanging and damaging each other. Tang officers loved tall black leather boots (pointed, upturned toes), though they switched to cloud-toe shoes or hemp shoes for court/regular duty. Ancient Chinese military clothing reached new heights in this golden age of ancient Chinese armor and Hanfu military dress.

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960 CE)

This chaotic half-century saw rapid regime changes and constant upheaval, so clothing and armor mostly carried over from late Tang without much innovation. Mingguang armor pretty much disappeared. Armor shifted back to full scale construction, often in two-piece sets: one piece combining shoulder guards and arm guards; the other linking chest/back plates with leg guards, connected front-to-back by two shoulder straps over the top piece. Large-block leather armor remained in use, often paired with doumou helmets and neck guards. Chinese military armor by dynasty continued in transitional form here.

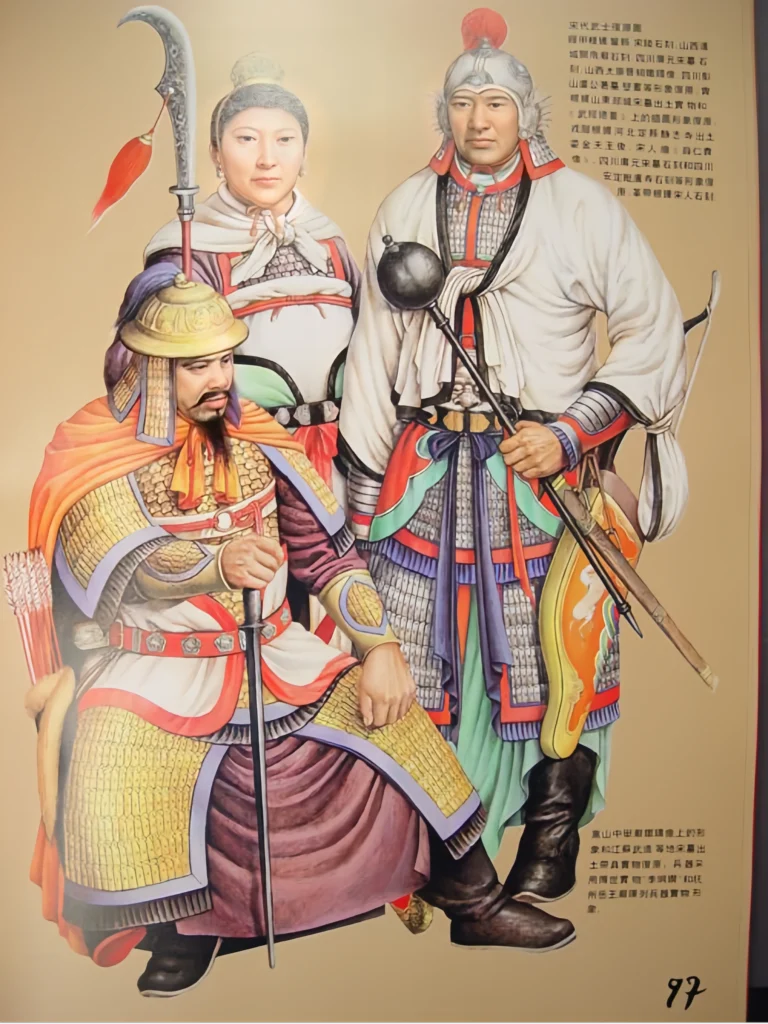

Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE)

Right from its founding, Song emphasized civilian control over the military, dividing power and keeping armies weak to prevent coups—this became a core “family rule.” It worked at first but led to bloated forces, chronic weakness, and repeated defeats. In 1127, the north fell to invaders, forcing the court south; the Southern Song was too fragile to invest much in military production. Armor manufacturing stagnated. Another big factor: gunpowder weapons gained real power by Southern Song, reducing the importance of armor (though it lingered for centuries).

Song military uniforms built on Five Dynasties styles with tweaks. The army split into imperial guards (jinjun—elite central forces) and provincial troops (xiangjun). Officers (ninth rank and up) had three outfits: court dress, public dress, and seasonal gifts from the emperor. Regular soldiers in combat wore basic armor and a “pizi” (leather helmet). (Imperial guard officers often wore more elaborate versions, while provincial troops stuck to simpler gear.) This reflects ongoing shifts in Chinese military armor by dynasty, ancient Chinese armor, and ancient Chinese military clothing.

Liao Dynasty (907–1125 CE)

Liao was founded by the Khitan people, long-time rivals to Northern Song until Jin conquered them. Early Khitan forces already used iron armor. Military dress split into two categories: Khitan style and Han style. According to Liao histories, armor drew heavily from late Tang/Five Dynasties and especially Song patterns. Upper structure matched Song almost exactly, but leg skirts were noticeably shorter. Front and back had square “huwei” (eagle-tail) plates covering the legs—a holdover from Tang/Five Dynasties. Abdominal protectors often hung from belts and were secured at the waist (like Song leather armor). A large round chest protector was a distinctive Liao feature. Besides iron, they used plenty of leather.

Khitan officers’ dress came in public and everyday versions—both round-collar, narrow-sleeve long robes similar to civilian men’s wear (everyday might be slightly tighter-fitting). Either could serve as battle dress.

Jin Dynasty (1115–1234 CE)

Jin was founded by the Jurchens. They crushed Liao, then overran Northern Song’s capital in 1126–27, forcing the Song south and setting up a century-long standoff until the Mongols wiped them out. Early Jin armor was half-body with knee guards. By mid-Jin, it became much more complete, with long, wide leg skirts matching Song coverage. Styles were heavily influenced by Northern Song. Military robes: round-collar, narrow-sleeve, reaching to the ankles—could be worn over armor as an outer layer.

Western Xia (Xixia) (1032–1227 CE)

Xixia was a multi-ethnic state founded by the Tangut (Dangxiang) people. They oscillated between alliances with Song and Liao before being crushed by Genghis Khan. Tangut warriors wore full-body armor: helmets, shoulder guards identical to Song; body armor resembled liangdang style, reaching above the knee—still mostly short armor, showing manufacturing lagged behind the Central Plains. Officers’ dress could double as military wear, similar to Liao Khitan styles with little obvious difference.

Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368 CE)

After unifying the Mongols in 1206 under Genghis Khan, they launched massive conquests—wiping out Western Liao, Khwarezm, Jin, Song, and pushing into the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The Yuan army was mostly elite cavalry: tightly organized, well-equipped, including early firearms. Armor was a standout feature. Body armor used net-like construction: outer layer covered in small copper/iron plates laced together, inner lining of cowhide—extremely intricate and arrow-resistant. Early Yuan (pre-conquest of China) used only Mongol national dress: “zhisun fu” (tight, narrow-sleeve robes, crossover or square collar, long to below knee or short to knee). Headgear: hats or wide-brimmed conical caps.

After conquering China and settling in Dadu (Beijing), they adopted Han-style court and public dress for officials to win over elites. Military uniforms for soldiers followed Tang/Song patterns. Boots were standard everyday wear. Other armors included willow-leaf scales, iron-ring mail (netted iron with cowhide lining, fish-scale overlapping—highly effective). Also leather, cloth-covered, etc. Another Mongol-style garment: “bianxian ao” (braided-line jacket)—similar to zhisun but with wide pleated lower hem, braided waistband, sometimes buttons. Used by officers, guards, and warriors.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE)

Ming rose from the Red Turban rebellions that toppled Yuan. Early Ming heavily invested in military production, advancing firearms and armor tech. Steel armor dominated—technically advanced, huge variety. Ming had the most detailed military rank system ever, so uniform distinctions were clearest. Officers (ninth rank+) had four types: court, public, everyday, and bestowed dress. Only everyday dress was common for military use; others were court/ceremonial.

When in uniform, soldiers could wear helmets/armor or cloth hats/caps (e.g., red military caps, loyal-quiet caps, small caps). A signature piece was the “pang’ao” (padded jacket): knee-length, narrow sleeves, cotton-stuffed, usually red—hence “red padded jacket.” Cavalry versions often had split fronts for riding. Combat helmets were mostly copper/iron (rarely leather). Officers’ armor used steel with “mountain” pattern plates—precise, lightweight. Soldiers wore chain-mail armor, plus iron-net skirts/pants and iron-net boots below the waist. Lower ranks typically wore shoes only, no boots.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 CE)

Qing was founded by the Manchus (descendants of Jurchens). Nurhaci unified tribes in the late 16th century, created the Eight Banners system, established Later Jin in 1616, then openly rebelled against Ming. In 1644, they entered Beijing with Wu Sangui’s help, crushed rebels, defeated Southern Ming, and unified China. Early Qing was still powerful under Kangxi. Long wars with Ming taught them firearms; they imported European guns/cannons and peaked in production quality/variety. As guns advanced, armor lost importance—early Qing still used it in battle, but by mid-Qing it was ceremonial only (parades/inspections). Combat troops wore uniforms or padded armor instead. Helmets (now called “zhou” again) split into officer, attendant, and soldier types.

After mid-Qing, when armor was phased out, uniforms became the sole military dress—full Manchu style. Officers wore court dress, python robes, patched robes (with rank badges on chest/back), and traveling robes (xingpao—the main battle uniform, similar to python robes). Headgear matched robes for civil/military. Soldiers’ uniforms were simpler: collarless short-sleeve jacket, mid-length wide pants, often with a horse jacket over top. Headwear: warm hats, cool hats, headscarves, felt hats. Officers wore boots; soldiers wore double-beam or ruyi-head shoes. Belts included court, auspicious, everyday, and travel types.

By late Qing, peace bred complacency; they clung to outdated “horsemanship is the Manchu foundation” ideas, ignored modern tech, and fell apart when Western powers arrived. The “self-strengthening” movement created new armies modeled on European lines—modern uniforms began here, blending old and new. Traditional military dress vanished after the Qing fell in 1911/1912. Typical late Qing helmet: lacquered iron or leather, with cross ridges, front visor, plume tube, rear silk neck/ear guards embroidered and studded. Armor: jacket with shoulder/axilla guards, front/back heart mirrors, trapezoid abdominal guard (“front dang”), side guards (left only, for quiver space), and split skirt tied at waist with tiger-head knee guards in the center.

An in-depth exploration of ancient Chinese armor and ancient Chinese military clothing, tracing how Hanfu military dress and Hanfu armor history evolved across the dynasties in this comprehensive guide to Chinese military armor by dynasty.

Want to explore more Ancient Chinese Clothing culture?

Check our Chinese Clothing Guide for authentic tips!

Responses