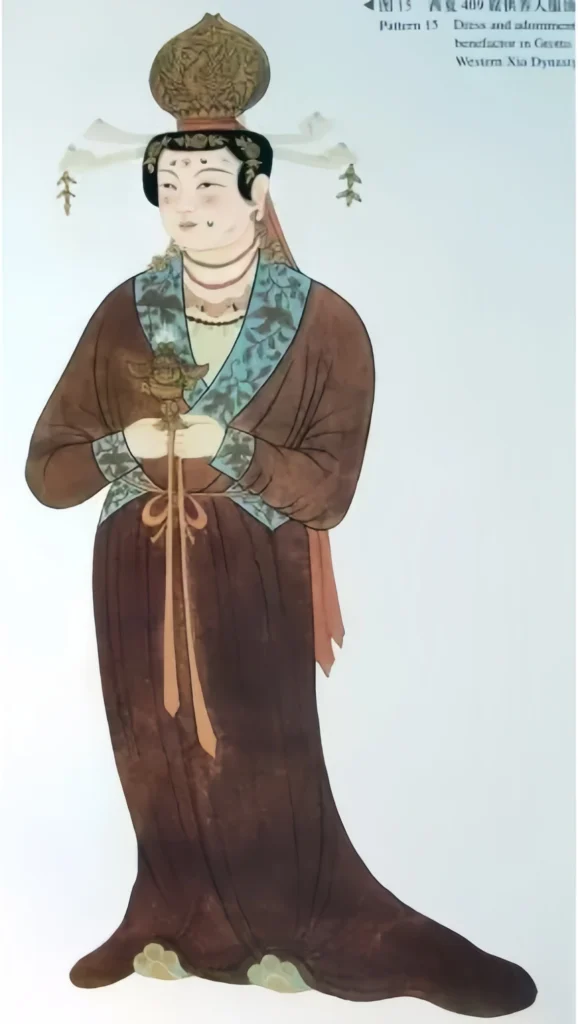

Common Decorative Patterns in Tang Dynasty Clothing

Tang Dynasty clothing patterns

Tang culture embraced the world with an open and inclusive attitude, absorbing and blending a wide range of foreign influences. Different cultures interacted, merged, and gradually formed a harmonious whole. Artists of the time were keen to depict exotic themes, foreign deities, and saints, while also learning from artistic styles and techniques different from their own. Decorative arts in the Tang dynasty reached an unprecedented peak. In terms of artistic achievement, Tang Dynasty clothing patterns, as well as broader Tang Dynasty patterns, stand on the same historical level as Tang poetry, calligraphy, and painting.

Popular decorative patterns of the period can be broadly categorized as bead-linked patterns, scrolling vine patterns, baoxiang floral motifs, roundel (grouped medallion) patterns, and geometric designs. These motifs, widely recognized today as classic Hanfu patterns, were commonly used in Tang brocades, gold and silverware, ceramics, and architectural decoration, forming an important part of traditional Chinese clothing patterns.

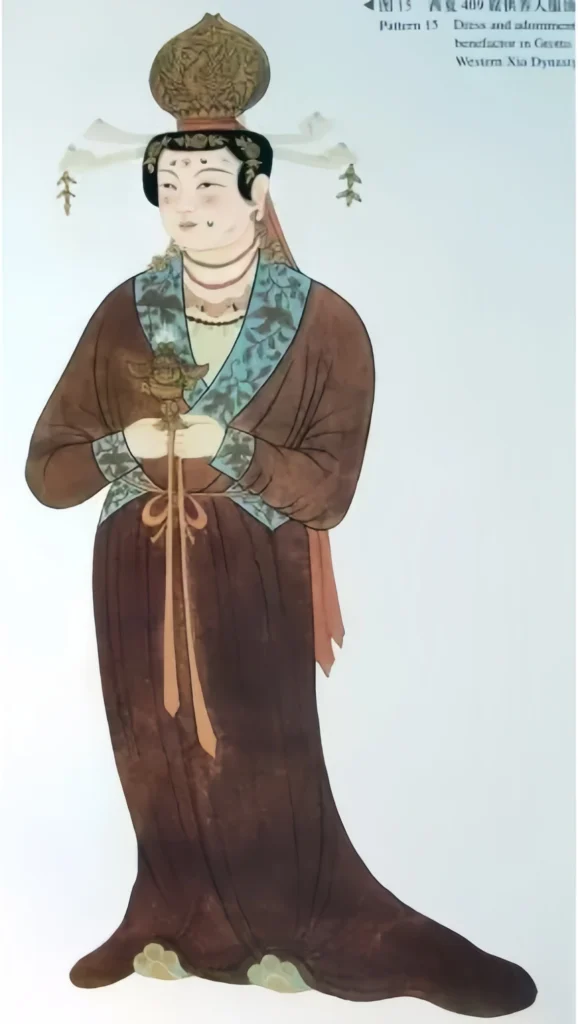

(1) Bead-Linked Medallion Patterns

The basic structure consists of a series of evenly arranged circular forms. The edges of the circles are decorated with linked beads, while the centers feature birds or animals. The spaces outside the circles are filled with four-directional radiating baoxiang motifs. This pattern was influenced by the Sasanian Persian Empire (226–640 CE) and may also have been a popular export design at the time. It was widely used from the Northern Dynasties through the mid-Tang period and became a defining element within Tang Dynasty clothing patterns.

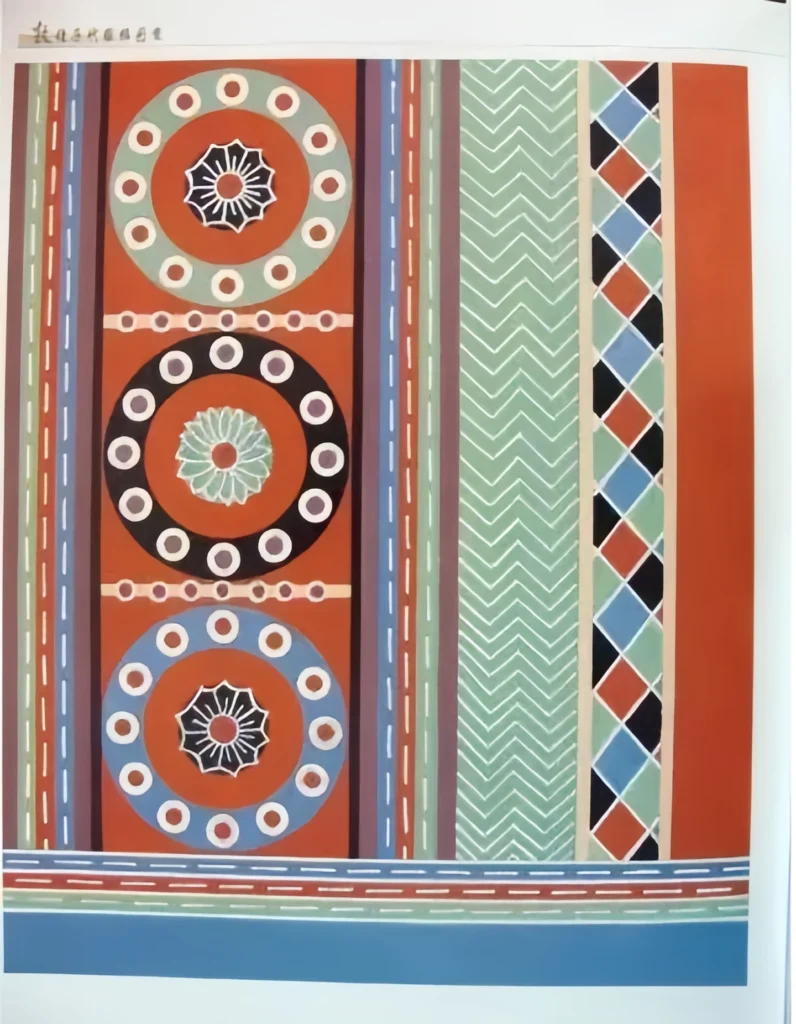

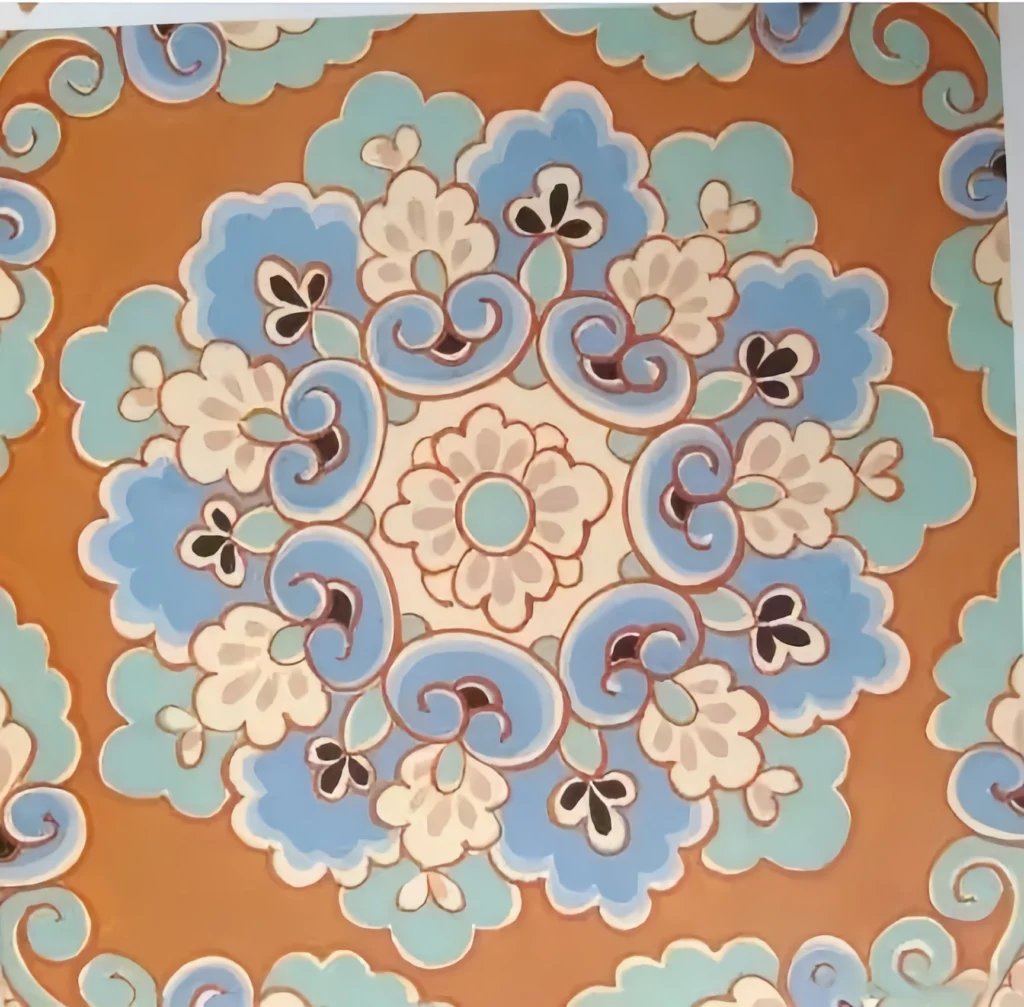

(2) Baoxiang Floral Patterns

These decorative floral designs are composed of blooming flowers, petals, buds, flower cores, and leaves, rearranged according to radial symmetry. The inspiration came from the aesthetic beauty of metal jewelry inlay techniques, combined with the natural elegance of various flowers. As one of the most representative Hanfu motifs, baoxiang floral patterns frequently appear in Tang textiles and ceremonial garments.

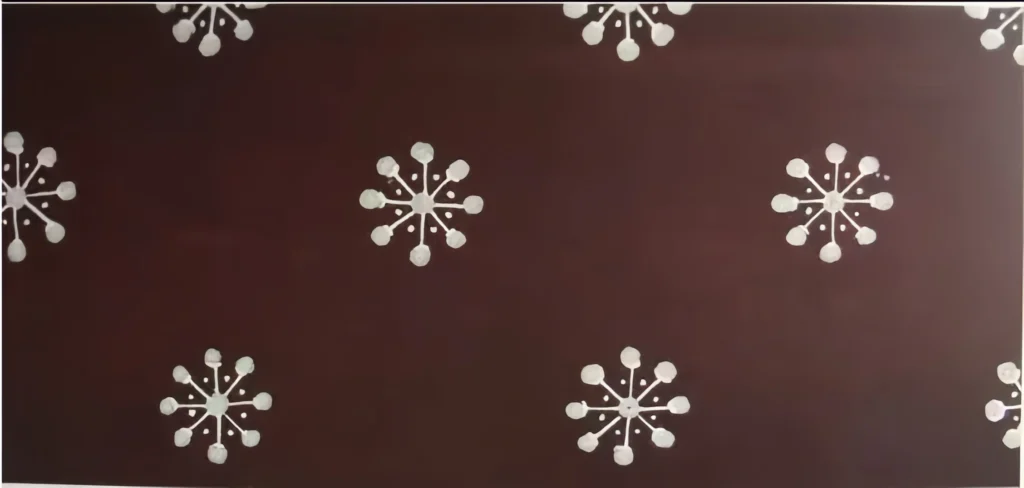

(3) Auspicious Brocade Patterns (Ruijin)

Derived from the natural form of snowflakes, these patterns are transformed into multi-sided, radiating symmetrical designs. They carry the auspicious meaning of “timely snow promises a good harvest,” reflecting symbolic thinking commonly seen in Chinese clothing patterns.

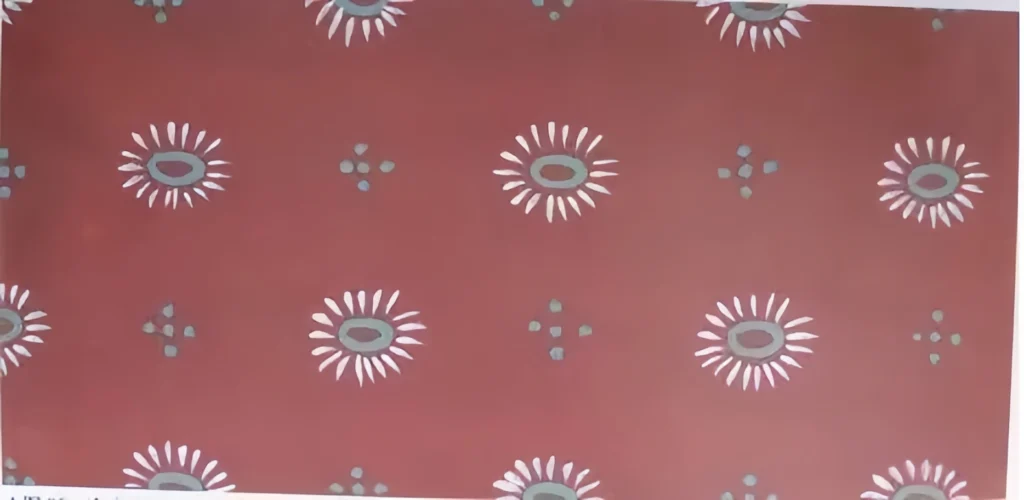

(4) Scattered Small Floral Clusters and Blossoms

Using the natural forms of flowers and leaves, small symmetrical floral clusters are arranged in a scattered pattern. This style was especially popular during the High Tang period and is often seen in Tang-era Hanfu patterns with a light and lively visual rhythm.

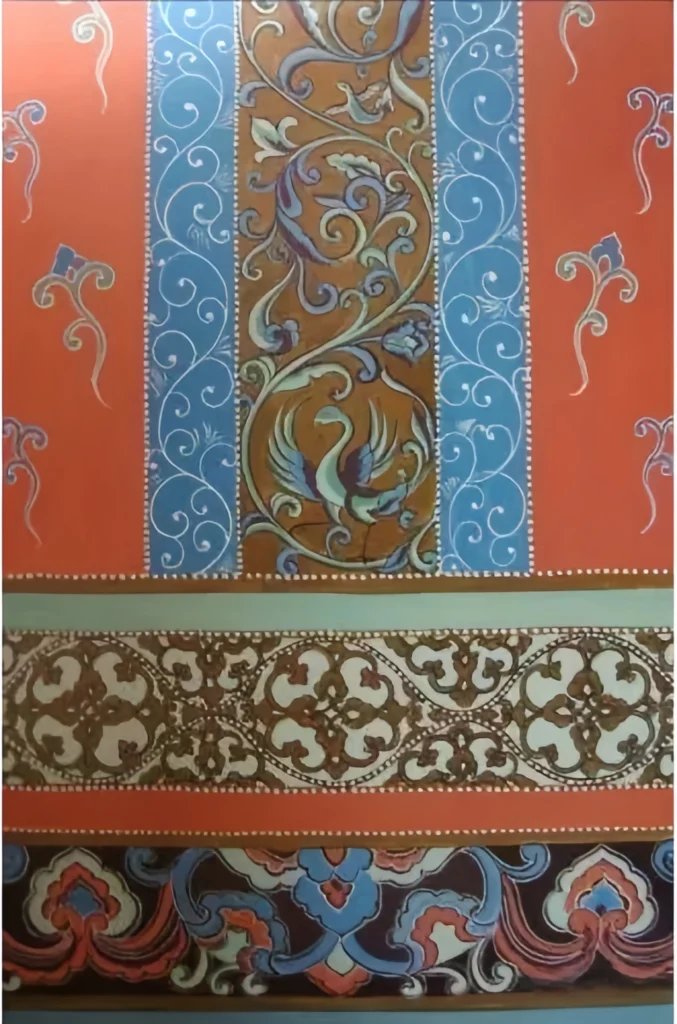

(5) Branch-Piercing Floral Patterns

Built on flowing, wave-like lines, flowers, buds, branches, leaves, and vines are combined into rich and continuous decorative compositions. These patterns were popular from the Tang through the Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties, and are also known as Tang grass patterns, making them one of the most enduring Tang Dynasty patterns in the history of Hanfu design.

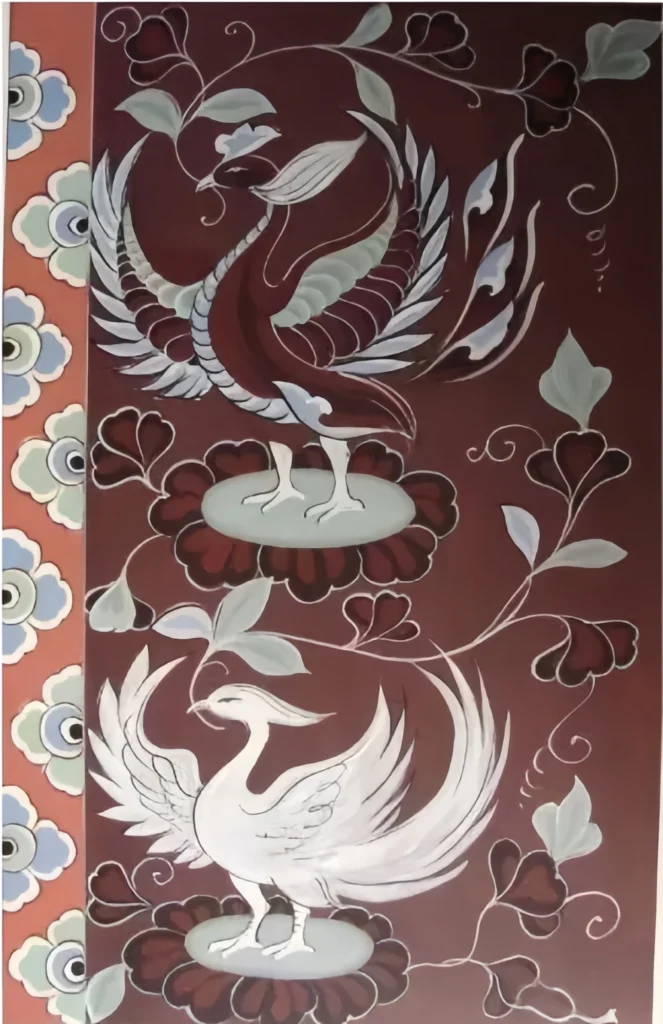

(6) Birds Holding Flowers and Grasses

This motif typically depicts birds such as luan birds, phoenixes, peacocks, wild geese, and parrots holding auspicious plants, beaded ornaments, endless knots, or flower branches in their beaks. Some are shown in flight, while others are perched. Such imagery reflects the symbolic richness often associated with traditional Hanfu motifs.

(7) Hunting Scenes

These appear either as freely scattered compositions or arranged within bead-linked medallion structures. Hunting scenes add a dynamic and narrative element to Tang Dynasty clothing patterns, especially in silk brocades intended for elite use.

(8) Geometric Patterns

Common forms include tortoiseshell, paired lozenges, checkerboard squares, double victories, interlaced ribbons, and ruyi shapes. During the Sui and Tang periods, such patterns featured full, rounded forms with prominent main motifs and open backgrounds, often using symmetrical compositions and bright, vivid colors. By the Five Dynasties period, patterns became more realistic and refined. For example, Shu brocades from Chengdu during the Later Shu featured designs such as Chang’an bamboo, Universal Joy, carved medallions, fertility motifs, jeweled grounds, square victories, lion medallions, elephant-eye motifs, eight-rhythm patterns, and iron-stem lotus. These pattern names continued to be used in the Song dynasty and had a lasting influence on Ming and Qing brocade designs, shaping the long-term evolution of Chinese clothing patterns.

Among these popular motifs, those derived from the Sasanian Persian style—using bead-linked circular frames as the main decorative border—are known as bead-linked patterns. Inside the circles, one often finds paired horses, birds, ducks, or Persian-style boar heads and standing birds. This style originated as a heraldic and decorative art form in the Sasanian Empire around the 3rd century.

It entered China during the Sui dynasty and flourished in the Tang. The Book of Northern History · Biography of He Chou records that early in the Sui dynasty, Persia presented bead-linked brocade. Emperor Wen ordered He Chou to replicate it, and his version was said to surpass the original. In the Tang dynasty, bead-linked patterns became the most distinctive and abundant decorative feature of Tang brocade, even exceeding the total output of other patterned silks of the time. These textiles were widely exported and enjoyed great popularity, firmly establishing their place in Tang Dynasty clothing patterns.

Bead-linked patterns were often combined with roundel (medallion) patterns, known today as tuanhua. This was a new development in Tang silk design. Using circular units as the basic decorative element, these patterns evolved from Persian motifs. Circular elements featuring figures, animals, or stylized foliage were originally common in Sasanian royal textiles and later spread widely through early medieval trade.

Bead-linked medallion patterns typically use symmetrical layouts. The designs inside the circles may feature traditional Chinese imagery or foreign-influenced motifs, including flowers, auspicious animals, or human figures. The defining feature, however, is the bead-linked border. This combination became the mainstream of Tang silk decoration, forming some of the most visually rich Hanfu patterns of the period. Excavated examples include brocades with bead-linked “gui” characters, bear heads, deer motifs, and knightly hunting scenes.

Building on the absorption and reinterpretation of Persian patterns, Tang artisans also created new designs with a distinctly Persian flavor, known as the “Lingyang Gong Style.” Historical records note that before 650 CE, imperial auspicious brocades featuring paired pheasants, mythical bulls, auspicious phoenixes, and swimming fish were created by Dou Shilun (Records of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties, vol. 10, by Zhang Yanyuan).

Dou Shilun, an early Tang official sent to Sichuan to oversee governance and imperial workshops, was later granted the title Duke of Lingyang, hence the name of the pattern. These designs retained traditional Chinese continuous layout structures while replacing bead-linked borders with floral rings or scrolling vines, and substituting Western mythological figures with Chinese animal themes. This compositional approach—placing animals within floral rings—continued in Chinese decorative art for several centuries and remains an important reference in the study of Hanfu motifs and Tang Dynasty patterns.

Want to explore more Patterns in Tang Dynasty Clothing?

Check our hanfu Guide for authentic tips!

Responses