Hanfu: Skirts and Lower Garments

Hanfu skirts, as the lower garment in Hanfu

Hanfu skirts, as the lower garment in Hanfu, have an ancient origin. As early as prehistoric times, people tied together leaves or animal skins to keep warm, creating the earliest form of a skirt. According to Shiming·Clothing written by Liu Xi in the late Eastern Han period, the word “qun” (skirt) comes from “qun,” meaning many small pieces joined together, referring to leaves or animal skins sewn into one piece.

It’s said that around 4,000 years ago, the Yellow Emperor established the system of “upper garment and lower skirt,” assigning different colors of clothing to different social ranks. At that time, the “chang” simply referred to a skirt. The Historical Records of the Five Dynasties states: “In ancient times, upper garments and skirts were joined together, with hems matching the clothing color and decorated with borders. From the era of Yao and Shun, there were six pleats and straight seams, and the borders were removed. In the Shang and Zhou dynasties, more decorations such as embroidery and colorful trims were added. The system itself existed long ago—later generations merely enriched the patterns.”

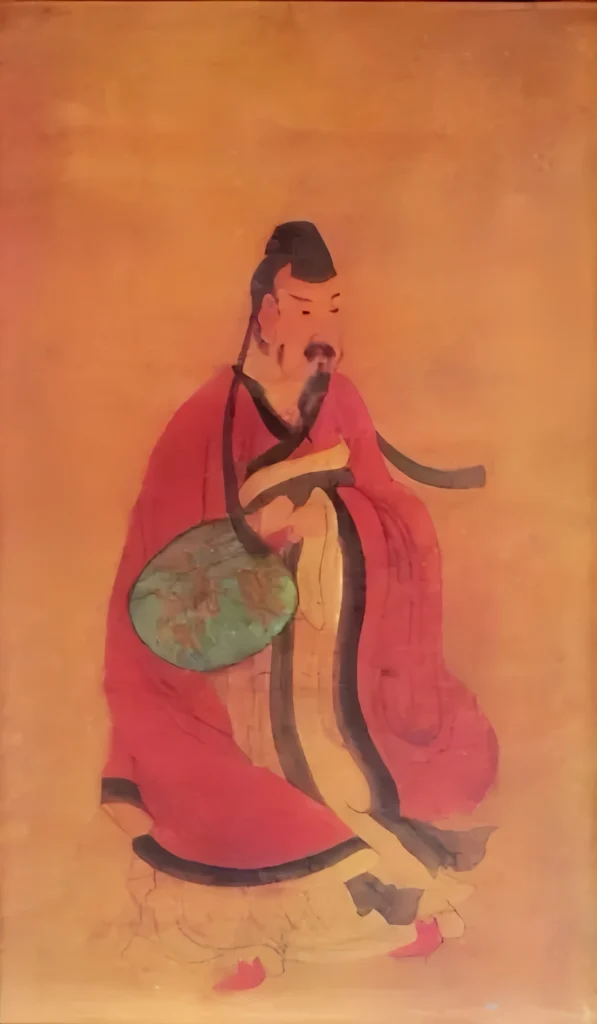

During the Xia, Shang, and Zhou periods, the Huaxia people of the Central Plains wore upper garments with lower Hanfu skirts, tied their hair up, and wrapped the right side of the collar over the left. A stone carving of a slave-owner found in Anyang, Henan, shows him wearing a flat-topped hat, a cross-collared right-over-left top, a skirt below, a large belt at the waist, leg wrappings, and pointed shoes—reflecting the general style of skirts in the Shang dynasty.

In the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, people commonly wore shenyi, made by joining the upper garment and skirt together. During the Han dynasty, Hanfu skirts became more widely worn. The tops were short while the skirts were long, which is clearly shown in surviving pottery figurines and dancing figurines. Skirts during this period all had pleats, known as pleated Hanfu skirt. Ordinary men sometimes also wore short tops with skirts. When laboring, people often tucked the skirt into their waistband to move more easily. Records of the Three Kingdoms · Wei · Biography of Guan Ning notes: “Ning often wore a black cap, a cloth top and trousers, and a cloth skirt.”

After the Wei and Jin dynasties, skirt styles increased. Besides the usual long skirts, there were crimson gauze layered skirts, red-and-blue patterned double skirts, red patterned silk skirts, and more.

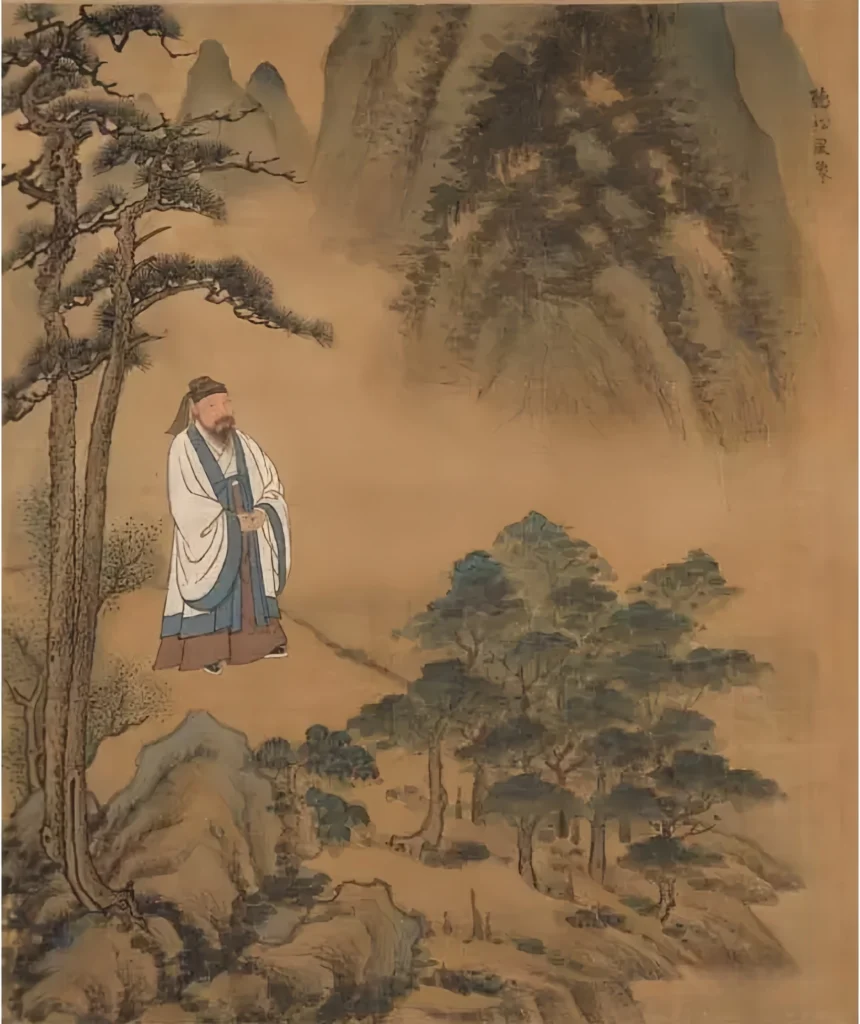

During the Two Jin and Sixteen Kingdoms period, striped skirts became popular. According to Book of Song · Biography of Yang Xin, when Wang Xianzhi served as Governor of Wu, he once wrote several lines of calligraphy on Yang Xin’s new white silk skirt while Yang was asleep. Yang Xin, who was already talented in calligraphy, improved greatly after obtaining this genuine piece. Skirts were commonly worn by aristocratic youth during the Six Dynasties, earning them the nickname “skirt-and-clog boys.” The History of the North · Biography of Xing Luan notes: “Xiao Shenzao was one of the ‘skirt-and-clog boys,’ and had not yet managed governmental affairs.”

Skirts of the Sui dynasty largely continued the styles of the Northern and Southern dynasties. Extra-long skirts that trailed on the ground were especially loved during this period, and striped skirts remained common. In the Tang dynasty, both the length and the width of Hanfu skirts increased noticeably, creating a fuller and more voluminous silhouette that was favored by people of all classes. The bright, colorful Tang pomegranate skirt became iconic.

During the Song dynasty, the Tang-style ruqun continued to be the main daily outfit. Song dynasty skirt tended to have soft, elegant colors, and the skirt body remained wide, often made with six, eight, or twelve panels, all with many pleats—classic pleated Hanfu skirt. The decorations on skirts were rich—painted designs, dye-resist patterns, gold-stamped embroidery, pearl embellishments, and more. Yellow skirts dyed with turmeric root were the most prestigious; red skirts were worn by dancers; and the bright, colorful pomegranate-red skirts were especially famous.

Influenced by minority clothing, Song tops could fasten either left or right, though right-fastening was more common. A jade ring called a yu huan shou was often hung from the ribbon at the center front of the Song dynasty skirt to weigh it down, keeping the skirt elegant and steady while walking.

During the Liao, Jin, and Yuan periods—when non-Han ethnic groups ruled—Han skirts mostly followed the traditions passed down from the Song dynasty. Skirts of the ruling Khitan and Jurchen peoples kept more of their own cultural features. For example, Khitan and Jurchen women wore chanqun, usually in dark colors, embroidered with connected floral patterns, pleated into six folds, and typically worn under round-collar tops.

The Ming dynasty restored many Han traditions, and Hanfu skirts continued the Tang-Song characteristics. The red skirts popular in the Tang dynasty became fashionable again. Long skirts with diverse patterns and many styles prevailed. Water Margin records: “(Hong Jiaotou) took off his clothes, hitched up his skirt, grabbed a staff, and struck with full force…”

During the Chenghua reign (1465–1487), a voluminous and elegant style called the Ming horsehair skirt became popular in the capital. At first, few people could weave them, making them expensive and only worn by wealthy aristocrats. As more weavers and sellers appeared, “high and low alike wore them,” and by the late Chenghua period, even court officials commonly adopted them (as recorded in Lu Rong’s Shuyuan Miscellany).

In the Qing dynasty, the Han tradition of “upper garment and lower skirt” was disrupted, and skirts gradually disappeared from men’s clothing.

Want the perfect Hanfu skirt today?

Check our How to pick & style your Hanfu skirt.

Responses