Hanfu in Artworks: A Timeless Beauty

Hanfu’s Artistic Journey

Hanfu’s stunning evolution spanned the solemnity of Han, the vibrancy of Tang, the elegance of Song, and the richness of Ming, only to be halted by political shifts in Qing. Yet, its aesthetic charm and cultural vibe kept influencing art forms, never fully broken by history’s harsh turns. The story of Hanfu in artworks is a journey across dynasties, blending cultural memory with visual beauty.

Hanfu in Ancient Paintings

Compared to Hu Fu, Qi Zhuang, or other minority outfits, Hanfu stands out for blending dignity with flow, liveliness with grace. Harmonizing these contrasts into one gorgeous robe is its true art. Ancient painters often used Hanfu in ancient paintings to convey virtue, elegance, and refinement.

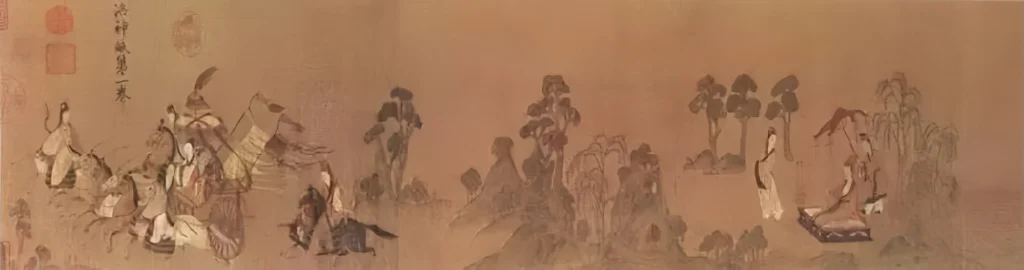

Take Gu Kaizhi’s Nü Shi Zhen Tu from Eastern Han—a painting gem. The women depicted are role models of courtly virtue: Feng Jieyu bravely shielding Han Yuandi from a bear, Ban Jieyu humbly declining Han Chengdi’s chariot invite. To showcase their virtues, every move had to feel dynamic yet gentle. Hanfu perfectly framed Gu’s brushwork for this.

In the fourth section, a lady sits at a mirror while a girl combs her hair. Wei-Jin Hanfu, with its wide sleeves and flowing robes, gives her an ethereal look. Despite the intricate silk layers, she avoids bulkiness, radiating noble poise. These secluded palace women exude stability with a spark of life.

This scene warns: everyone knows to groom their looks, but character matters more. As a model, her attire must be refined yet modest, her demeanor calm and kind. Hanfu’s robe sleeves and skirt hems layer softly, neither too plain nor flashy, highlighting elegance and grace while keeping a lively spirit that flows freely, not stiff or dull.

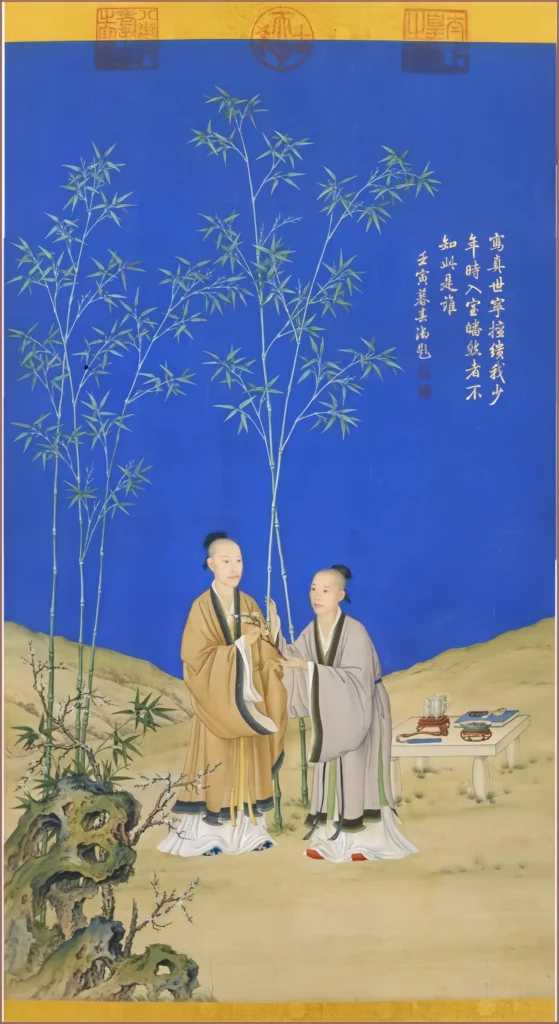

Though Qing’s policies enforced shaved heads and new styles, replacing Hanfu with Qi Zhuang, rulers secretly loved Hanfu. In private spaces beyond the palace, they wore it, enjoying a different vibe and proudly documenting it. Without this, we wouldn’t see Qing palace art, like Yongzheng’s stern diligence, Qianlong’s “perfect ten” pride, or Jiaqing’s mild charm, all captured in Hanfu in artworks of imperial leisure. Hanfu offered them a hidden world of fun.

Especially in Lang Shining’s Ping An Chun Xin Tu, Yongzheng and Qianlong share a rare moment. Dressed in Hanfu amid bamboo and rocks, they look like humble scholars, passing plum branches like a typical father-son duo. Middle-aged Yongzheng (Yinzhen) seems otherworldly, while young Qianlong (Hongli) shines like a breezy scholar. Hanfu fits the body naturally yet allows flowing movement, giving stressed emperors a “half-day escape” feel. Its free spirit beats the practical Qi Zhuang, tempting rulers to sneak in some fun outside politics.

Hanfu on Ceramics

Though Hanfu faded from history in Qing, its beauty lived on. Beyond court ladies’ paintings and imperial leisure art, Hanfu on ceramics kept the aesthetic alive in official and folk kilns.

During Kang, Yong, and Qian’s reigns, ceramic figure paintings boomed with a wealthier, growing society, mirroring the times.

Take Wu Cai porcelain, a Yuan invention with vibrant colors. Kangxi-era “Four Concubines Sixteen Kids” pieces show elegant Hanfu-clad ladies with many children, reflecting hopes for big families. Their graceful, understated Hanfu lines echo China’s timeless female ideal: virtuous, neat, and gentle. The layered design hints at depth over flash. In peaceful times, Hanfu’s elegance brings a laid-back, detail-loving lifestyle people craved.

Compared to Wu Cai, Fen Cai porcelain pops with vivid, lifelike hues, emerging late in Kangxi. Yongzheng and Qianlong’s Fen Cai lady portraits feature detailed, colorful Hanfu with spot-on accessories, enhancing flowing Ru skirts. These bold paintings show dancing figures, exuding prosperity as robes sway, touching later generations’ hearts and flowing through history. In China’s last feudal peak, traditional Chinese clothing like Hanfu remained a core memory of style.

Hanfu in Literature

Hanfu doesn’t just highlight women’s grace—it boosts men’s charm too. Beyond post-reform emperors’ love for it, it was a male allure staple early on, woven into poetic longing. The image of Hanfu in literature captures both elegance and romance.

Shi Jing • Zi Jin opens with: “Qing Qing Zi Jin, You You Wo Xin.” “Qing Qing Zi Jin” means a blue cross-collared robe, a scholar’s go-to, often linked to Hanfu’s collar. That scholar in Hanfu? He’s the one tugging at her heart. Who was he? Unclear, but a simple robe paints him as breezy, cloud-like, jade-smooth, pine-tall—truly “one-of-a-kind” in her eyes.

As beauty incarnate, Hanfu extends a person’s aura, a vibe symbol. Imagine “blue suit” or “blue tie” carrying that poetic love today—those lack the charm.

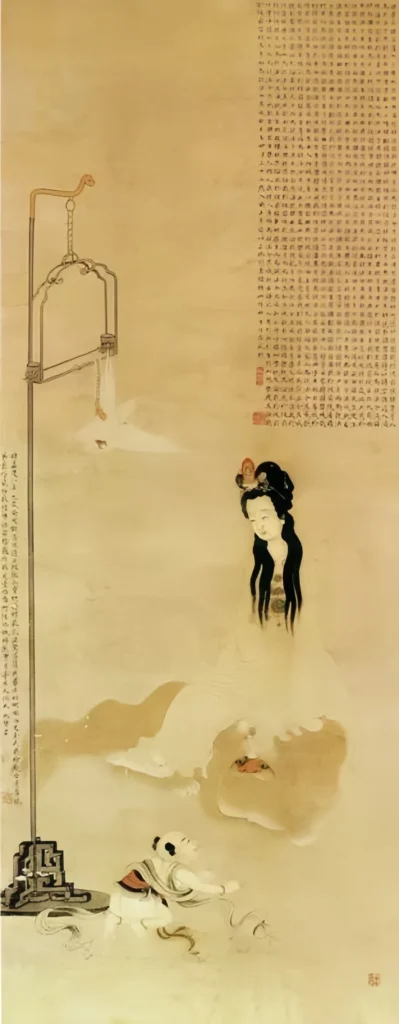

This woman’s affection ties to a daily robe. Even Cao Zijian, the genius, pictured his muse in Luo Shen Fu: “Her form flutters like a startled swan, glides like a wandering dragon, glows like autumn chrysanthemums, flourishes like spring pines. Faint like clouds veiling the moon, drifting like wind-blown snow.” Only Hanfu’s flow fits this fairy tale—clouds over moon, wind through snow, chrysanthemum face, pine body. As she steps, nature dazzles, yet her grace outshines all. Cao’s words and imagination craft his dream goddess, with Hanfu’s wide sleeves and flowing skirts making her stand tall and divine.

That’s Hanfu—a dance, a painting, a poem, a myth. It proves our ancestors’ noble spirit, rising beyond practical needs to savor luxury’s beauty. The presence of Hanfu in artworks shows how this traditional Chinese clothing has dreamed on for a thousand years.

Responses