Hanfu Elements: The Yun Jian – A Key Feature of Han Clothing

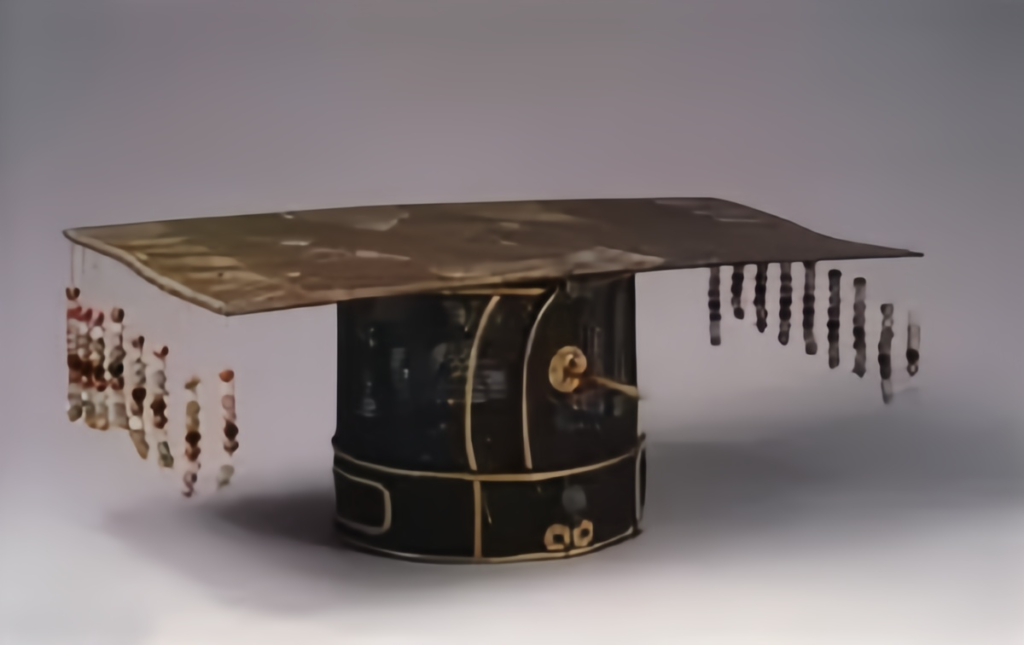

Yun Jian

“Lian Chui with Zi Tou Sheng, gold-embroidered Yun Jian with jade tassels.

Learning the Tian Mo dance to form a team, Chang’an welcomes foreign monks again.”

— Ming Yang Ziqiu, Shun Di

The Yun Jian, also known as a shawl, is crafted from silk, satin, or brocade, often adorned with four-sided cloud patterns and vibrant embroidery. It glows like clouds reflecting the sun after rain or a rainbow in a clear sky—hence the name Yun Jian.

The Yun Jian is a decorative piece worn over the shoulders, a standout feature of Han Chinese clothing. Its patterns are rich with meaning, blending artistic symbols, numerology, and deep cultural wisdom. It’s also a testament to how the Han people absorbed foreign clothing styles, blending and transforming them into their own unique fashion gem. Plus, it’s a brilliant example of merging flat and 3D design in Chinese clothing history.

Before Qin and Han, no written records mention it, but its style hints at influence from northern nomadic cultures—a foreign flair. The earliest visual is in Dunhuang’s Sui murals, where a sinicized Guanyin Bodhisattva sports a Yun Jian. It boomed among Han people, especially in Tang and Song, where the elite rocked “Five Cloud Fur” outfits, making Yun Jian a fancy staple.

In Sui and Tang, though seen on foreign-inspired Bodhisattvas, it tied closely to Taoist ideals. Despite its foreign roots, the Han reverence for the heavens turned it into their own, embodying a “harmony of heaven and human” vibe—a grand cultural fashion win.

Yuan Shi • Yu Fu Zhi notes: “Yun Jian, shaped like four hanging clouds, blue-edged, yellow silk with five colors, inlaid with gold.” By Ming and Qing, it became everyday wear. Qing Bai Lei Chao • Fu Shi: “Yun Jian, a women’s shoulder decor,” and Li Yu’s Xian Qing Ou Ji: “Yun Jian protects the collar from oil stains, a smart design.” In Qing, it grew into a must-have for young brides, worn during festivals or weddings. After the Republic, it faded, shifting to a key element in traditional opera costumes.

The Yun Jian’s design echoes Chinese architecture, emphasizing four-sided harmony with a “heaven and human unity” vibe. Rooted in Eastern thought, it reflects a holistic approach to nature’s balance. As one of the world’s earliest farming nations, China’s agricultural roots shaped a deep connection to weather and survival, mirrored in Taoist “heaven and human unity” philosophy. Even 2,000-3,000 years ago in the Spring and Autumn period, ancients valued “following nature”—a harmony Yun Jian creatively embodies in Hanfu culture.

Most traditional Han clothing uses flat cuts, but Yun Jian is tailored to fit, adjusted to a woman’s shape with 3D draping for a perfect shoulder fit. Styles include split Yun Jian, four-sided Yun Jian, beaded Yun Jian, and versions with or without collars. Its structure radiates or spirals from the neck, with four or eight segments, symbolizing sun worship and the seasons or eight auspicious directions, aligning with ancient blessings of harmony.

The “Xia Pei” is often mistaken for Yun Jian. Xia Pei, part of ancient women’s ritual attire like a modern shawl, was a status symbol for noblewomen since Song, with designs varying by rank, similar to officials’ badges. Ge Zhi Jing Yuan, citing Ming Yi Kao, describes Ming Xia Pei: “A woven piece over the robe, front and back matching its length, split in front, draped over shoulders and back, called Xia Pei.” In Qing, it added embroidered patches and colorful edges, featuring birds, not beasts.

Today, Yun Jian has lost its original cultural depth, mostly serving as a visual statement. Folk customs add silver bells to the tassels—new brides’ movements make them jingle rhythmically, adding a musical flow and boosting a lively, spirited charm.

Magnificent website. Lots of useful information here. I am sending it to a few pals. And of course, thank you in your sweat!