Hanfu Style: The Dao Pao

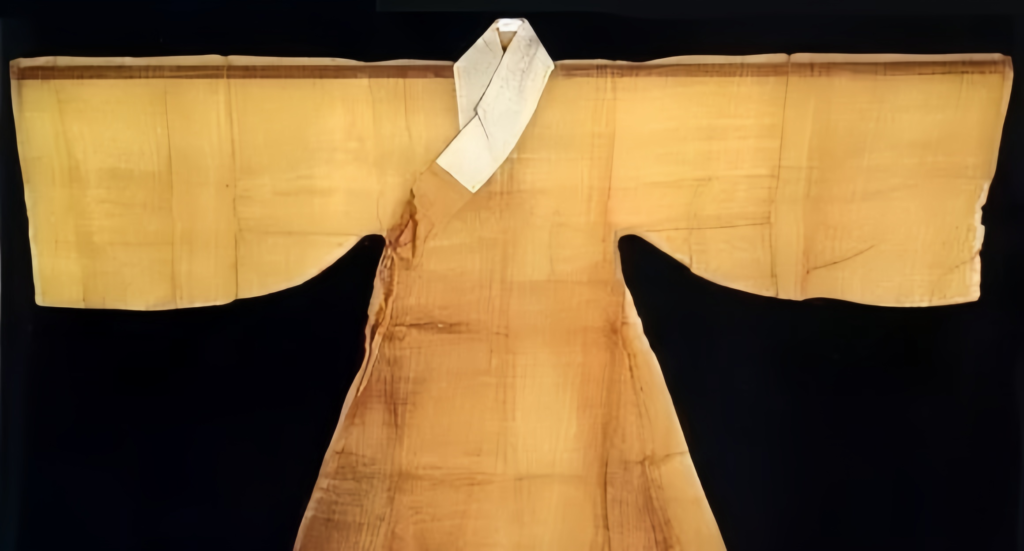

The Dao Pao, a Hanfu style from the Ming Dynasty, started as a men’s at-home outer layer and could double as an under-robe.

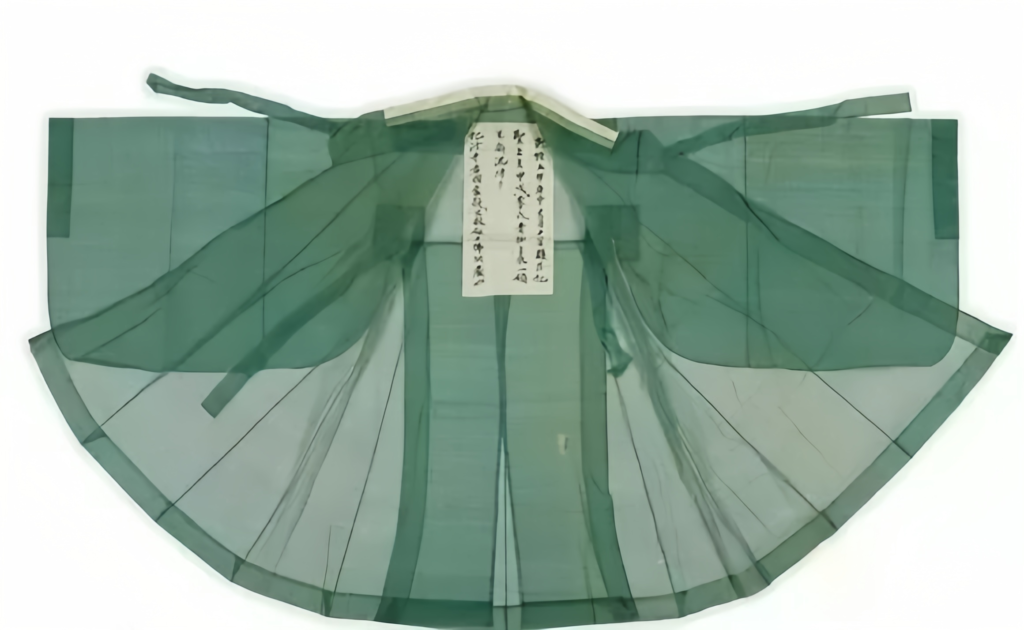

It features a straight collar, wide front overlap, side slits, and a hidden flap, tied with a sash. The collar often has a white or plain protective trim. Sleeves can be straight or wide with cuffs. Pair it with a silk sash, cloth belt, or broad sash.

In late Joseon Dynasty, the sash widened and shifted closer to the center.

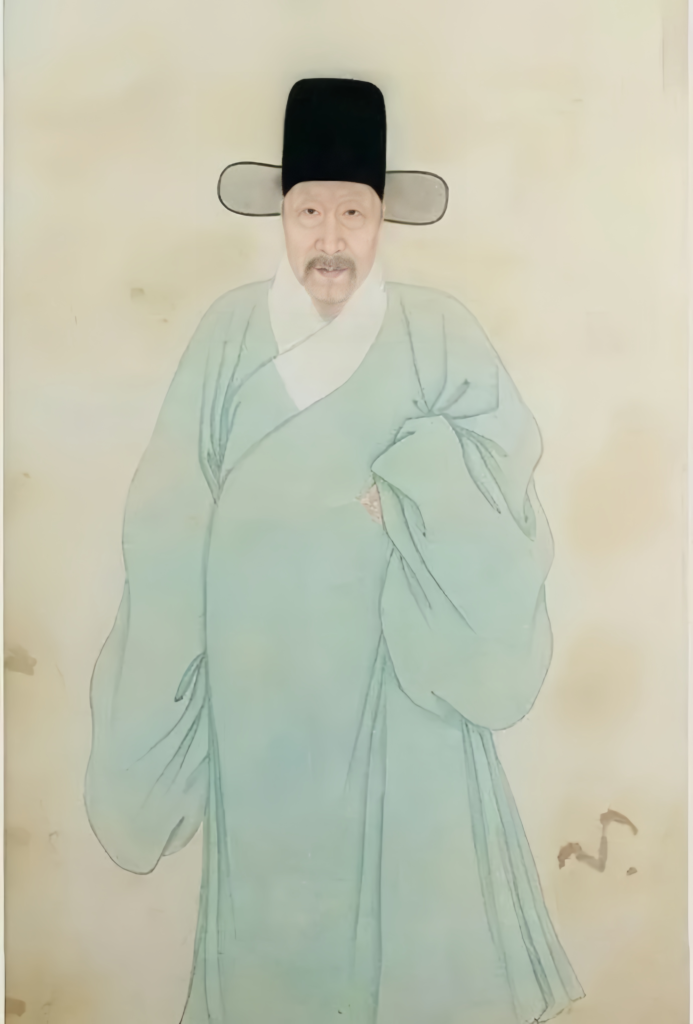

Dao Pao wasn’t just for scholars or formal wear—it was everyday home attire for common laborers too. Its trends shifted with hidden flap designs, length, and sleeve width. Ming novels and notes show sleeves growing wider, with big, long ones stealing the spotlight. Ming’s Feng Menglong in Gua Zhi Er’s Zi Di describes youth fashion: “White silk shirt, peach-red pants, Dao Pao with big sleeves, puffer shoes with low heels.” By late Ming, sleeves got exaggeratedly large. Ye Mengzhu’s Yue Shi Bian details the shift: “Clothes I saw as a kid hung long past the feet, sleeves under a foot wide; later, they shortened to the knees, sleeves stretched to three feet, brushing boots when bowing, piling up—inside and out. Shoes went from deep to barely an inch.”

Dao Pao uses a one-piece cut (top and bottom seamless), straight collar, right-overlap front, with an inner straight-cut flap. Sleeves vary from straight to wide.

The collar often has white or plain trim, tied with a sash. Side slits connect fabric pieces with two fixed pleats (or none), tucked into the back flap, called the “hidden flap.”

Guesses About the Hidden Flap

The hidden flap often joins three fabric pieces (Zhu Shi Shun Shui Tan Qi); it can have three pleats or none. With the shirt’s fabric, it totals twelve pieces (two front, two inner, two back, three per flap)—mirroring Li Ji • Shen Yi’s “twelve widths for twelve months,” symbolizing six yin and six yang. Its exact design remains a mystery, with no full recreation yet.

Ming-Era Records

Gu Bu Gu Lu notes: “Pleated pants are military wear, short- or sleeveless, with horizontal and vertical pleats below. Long sleeves make Ye Sa; a middle line turns it into Cheng Zi Yi. No line? It’s Dao Pao or Zhi Duo—common home wear. Lately, Cheng Zi Yi and Dao Pao seem too plain; scholars at gatherings flaunt Ye Sa, favoring military over elegant—I don’t follow.”

Yue Shi Bian adds: “Robes in floral or plain silk, gauze, or satin—fancy ones use thick cocoon silk or fine Ge in summer, beyond commoners’ reach. Simple ones use purple or white cloth in winter, off-limits for servants… Kids saw long robes with small sleeves; now they’re knee-length with three-foot sleeves, brushing boots when bowing.”

Jin Ping Mei Ci Hua (Chapter 30): “Manager Zhai stepped out in cool shoes, silk socks, and a silk Dao Pao.”

Feng Menglong’s Yu Shi Ming Yan (Volume 1): “The pawnshop faced Jiang’s door. How was he dressed? A Suzhou-style hundred-bristle hat, fish-belly white lake-silk Dao Pao—matching Jiang Xingge’s usual look.”

Shi Tou Shou (Chapter 4): “Fang leaned by the door, eyeing a youth passing by. A trendy short-brim hat, autumn-scent soft-gauze Dao Pao, black shallow-toe boots, white silk socks, water-green crepe jacket, peach-red crepe pants, a red-gold fan with amber drop, and a shiny gold ring.”

Yun Jian Ju Mu Chao (Volume 2, Customs, Clothing): “Cloth robes, once scholar staples, now seem cheap. The poor flaunt thin silk for a touch of glam; rogues grab old fabric, remaking it to mingle with rich kids—a oddity. Spring demands red shoes. Young scholars wear light-red Dao Pao. Shanghai students rock wool Dao Pao in winter, green umbrellas in summer—even the poorest, like Si Dan, can’t skip it. Ten bushels of wheat? Add a wool cap and hat, even flashier. I’m the poorest, sticking to plain, but lately forced into colored robes—customs shape even the wise.”

Joseon Dao Pao Legacy

Men’s robes were short, pants long and loose, often with vests or outer Dao Pao/long robes. Dao Pao, once scholar casual wear, became a men’s formal outing choice—single, lined, or padded. Its style traces to Ming (China), its suzerain, with widened sashes shifting centerward in late Joseon. But with unique culture and habits, Joseon Dao Pao evolved its own flair. Post-Ming fall, clothing localizing, its hidden flap grew distinct from Ming’s.

Responses