Evolution of Belt in Hanfu Fashion

The Hanfu belt evolution reflects a rich tapestry of Chinese cultural history, blending practicality with profound symbolism. From their origins as simple fasteners to their role as markers of status and propriety, Hanfu waistbands have undergone significant transformations. This blog explores the fascinating journey of Hanfu belts, focusing on their materials, styles, and cultural significance across dynasties.

Early Beginnings of Hanfu Waistbands

In ancient China, Hanfu waistbands were essential for securing flowing robes, ensuring a snug fit for daily activities. Beyond utility, they were imbued with cultural meaning, symbolizing propriety and respect. Failing to wear a waistband in formal settings was considered a breach of etiquette, as noted in historical texts like Yuzao from The Book of Rites. Early waistbands were divided into two main types: fabric waistbands (taodai) and leather belts (gedai), each with distinct roles based on gender and status.

Ancient waistbands came in many forms and styles but can be broadly divided into two categories:

Fabric Waistbands: Made from woven silk, cotton, or hemp, collectively called “taodai” (cord belts).

Leather Waistbands: Crafted from raw or tanned leather, known as “gedai” (leather belts).

Before the Qin and Han Dynasties, leather belts were mainly used by men, while women typically wore fabric belts, as noted in Shuowen Jiezi: “Men wear leather belts, women wear silk.” However, men also used fabric belts, and women, such as Tang and Song palace maids in round-collared robes, sometimes wore leather belts. Historical records, like Yuzao, show that pre-Qin waistbands already had distinct ranks, colors, and decorations: “The emperor wears a plain belt with red lining and full edging, nobles use plain belts with edging, officials have plain belts with hanging edges, scholars wear plain belts with lower edging, gentlemen use brocade belts, and disciples wear white silk belts…”

The position of the waistband varied by clothing style. For example, during the Warring States to Western Han period, those wearing curved-hem robes tied the belt at the hem’s tip to secure it, with the height depending on the hem’s length.

Both types of waistbands evolved alongside clothing, using methods like direct tying (including button ties) or accessories like belt hooks and rings. While fabric and leather belts developed in parallel, they influenced each other.

Fabric Waistbands (Taodai)

Taodai is the general term for silk or fabric waistbands, also called “tao,” “zu,” or “dai” depending on specifics.

Based on weaving techniques, structure, color, and function, fabric waistbands had names like gaodai (white silk belt), suzu (plain cord), diedai (mourning belt), meitao, pantao, chitao (red cord), luandai (phoenix belt), and dada (large belt). Different parts of the belt had unique names: the knot was called “choumou,” the hanging part “bili,” a loose knot “niu,” and a fixed knot “di.”

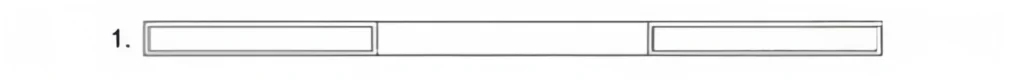

Taodai came in two styles:

Flat Strips: Ranging from 1 to 10 cm wide, either woven or braided.

Cord-like: Round and braided, varying in thickness.

Lengths ranged from 1 to 3 meters, allowing one or multiple wraps around the waist. Tying methods varied, with knots tied at the front, left, right, or back.

Materials included wool, hemp, silk, and cotton, in plain or patterned designs. Patterns were often embroidered or woven into the belt, blending utility with beauty through intricate craftsmanship and vibrant colors.

Fabric waistbands weren’t just simple cloth or rope. As early as the Spring and Autumn period, alongside leather belt hooks, fabric belts began using hooks for fastening. Later, accessories like taohuan (belt rings) emerged. While leather belts became more formalized and tied to official attire, fabric belts dominated daily life, especially in the Song and Ming Dynasties. Dreams of Splendor records a dedicated belt shop in Hangzhou’s Shapi Lane during the Song Dynasty, and by the Qing Dynasty, belt guilds still thrived.

The terms “tao” and “zu” originally referred to different weaving structures in pre-Qin times, but later records used them interchangeably. These terms applied not only to waistbands but also to clothing ties, trouser belts, shoelaces, and decorative cords.

These belts weren’t merely functional. Intricate embroidery and woven patterns added aesthetic appeal, blending utility with artistry. By the Song Dynasty, as recorded in Dreams of Splendor, dedicated belt shops thrived in Hangzhou, highlighting their cultural and commercial significance. For a deeper dive into Song Dynasty fashion, check out this article on Chinese clothing history.

Direct Tying

The simplest way to secure a waistband was tying the ends directly, often using common knots.

Waistbands tied outside robes or dresses varied by era and style. For example:

From pre-Qin to Han and Tang Dynasties, women’s ruqun (blouse and skirt) often had the skirt covering the top, so fabric belts were tied outside for both function and beauty.

In Wei-Jin and Tang periods, styles like shanqun (shirt and skirt) or half-sleeved tops rarely used outer waistbands. By the Song and Ming Dynasties, with the rise of beizi and skirt-over-top styles, skirt sashes often replaced waistbands, though belts were used during labor to secure hemlines for convenience.

Women’s robes typically had belts tied outside. After the Han Dynasty, women’s robes were less common among commoners, mainly seen in imperial ceremonial dresses or palace maids’ attire (using leather belts). By the late Ming, women’s long robes (changshan or large-sleeved shirts) became popular, often paired with fabric belts. These were sometimes called “sweat scarves,” embroidered or gilded, doubling as headbands.

In Ming daily life, men sometimes skipped fabric belts for a carefree look.

Accessory Tying

Beyond direct tying, fabric belts used accessories like hooks and rings. By the Southern Song, taohuan (belt rings) appeared, initially as simple rings or hook-and-ring pairs. Later, craftsmen designed symmetrical components with intricate patterns for mutual fastening. Some rings were a single piece with two buttons or loops on the back, paired with a clasp on the belt to adjust length. Despite changes, they were still called taohuan.

By the Qing Dynasty, as clothing styles shifted, hooks and rings became less common, turning into collectible or decorative items.

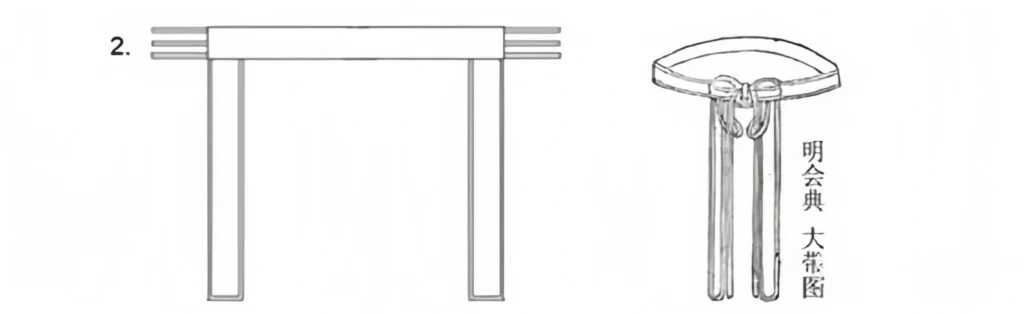

Ming Dynasty Large Belt (Dada)

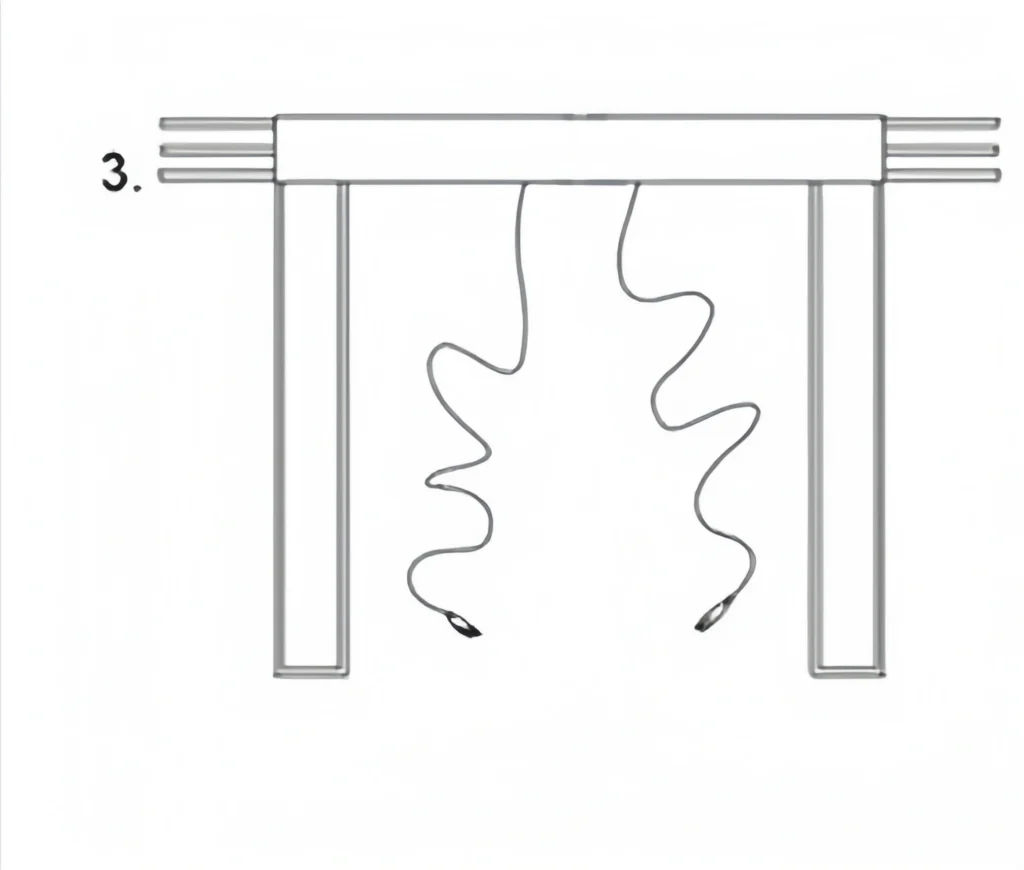

Historically, large belts (dada) were flat strips, but in the Ming Dynasty, new designs emerged. The hanging part (shen) was separated and sewn to the belt’s lower ends, secured with loops, thin cords, or buckles. Some included woven cords (zu) for decoration and stability. Unlike official belts, civilian large belts had fewer restrictions but shared features like bordered edges and plain bodies.

Type 1: The traditional flat strip, as long as the waist, about 9 cm wide. Hanging parts (shen) and loops (knotting parts) were 99 cm long and 9 cm wide, with separate cords. Less rigid, it was used for Ming deep robes and Taoist attire due to its slightly casual look.

Type 2: An improved design with the hanging part sewn to the belt’s lower end, tied with thin cords or buckles, and adorned with decorative loops (butterfly knots). The belt was 9 cm wide, with 64 cm long, 9 cm wide hanging parts and 1 cm borders, matching Ming Hui Dian records.

Type 3: Similar to Type 2 but without loops, using thin cords and buckles. Excavated artifacts from Dingling Tomb show this style, with cords fixed to the belt’s inner back, tied in front with a double-coin knot. The belt was 9 cm wide, with 64 cm long, 9 cm wide hanging parts, 1 cm borders, 27 cm long cords (0.5 cm wide), and 100 cm cords with 12.5 cm tassels, sewn 19 cm apart.

Large Belt (Dadai)

Unlike regular fabric belts, the dadai was a ceremonial belt used for formal occasions with attire like imperial robes, sacrificial garments, deep robes, or straight gowns.

The term dadai applied to both silk and leather belts, with similar symbolic meanings. In some cases, both were used together. In certain texts, dada is a general term for fabric belts, and its hanging part (shen) sometimes referred to the entire belt.

As early as pre-Qin times, dada had rank distinctions, with detailed regulations in texts like Yuzao in The Book of Rites (“Officials’ large belts are four inches wide… The emperor’s plain belt has red lining and full edging…”) and New Tang History (“Large belts are plain with red lining, bordered with red brocade…”).

While colors and materials varied across dynasties, the presence of a hanging part (shen) was consistent. In the Ming Dynasty, dada evolved significantly: belts were shorter, secured with buckles or ties, and lacked natural hanging parts, so shen was sewn on, highlighting its importance.

Fabric Belt Appreciation

Warring States: 72 cm long, 3.5 cm wide, with a hook at 3.5 cm from the left and eyelets at 3.5, 7, and 9.5 cm from the right (Changsha Chenjiadashan Chu Tomb).

Warring States: 106 cm long, 0.5 cm diameter, with two hooks (Changsha Chenjiadashan Chu Tomb).

Warring States: Waistband with hanging ornaments (Mashan Tomb No. 1).

Han Dynasty: Reconstructed silk belt.

Taodai vs. Gongtao: Taodai refers to waistbands, while gongtao are decorative fabric strips hanging from the belt, often colorful with long tassels, adorned with jade or gold ornaments.

Hanfu belt evolution and Modern Revival

The Hanfu belt evolution is more than a fashion story; it’s a reflection of Chinese societal values. Belts symbolized hierarchy, with colors and materials denoting rank, as seen in The Book of Rites. Today, the Hanfu revival movement has reignited interest in these traditional garments. Modern designers draw inspiration from historical fabric waistbands and leather belts, blending them with contemporary aesthetics. Enthusiasts can explore authentic Hanfu designs at Hanfu Story, a platform dedicated to preserving this cultural heritage.

Responses