Hanfu’s Fashion Journey: From Tang’s Glam to Ming’s Grandeur

Hanfu fashion, the traditional clothing of the Han Chinese, is a cultural phenomenon that’s thriving in 2025. Sparked in 2003 by Wang Letian’s bold hanfu walk in Zhengzhou, the modern hanfu movement has grown from online forums to a global craze, fueled by fans, researchers, and a booming industry. This blog explores hanfu fashion through three iconic eras—Tang, Song, and Ming—highlighting their unique styles, historical quirks, and modern appeal. Let’s dive into this dazzling journey!

The evolution of Hanfu from Tang’s vibrancy to Ming’s grandeur showcases China’s fashion legacy. Want to explore this journey? Learn more!

Hanfu, the traditional clothing of the Han Chinese, is more than just pretty outfits—it’s a cultural vibe. The modern hanfu movement kicked off in 2003 when Wang Letian, an ordinary electrician, strutted through Zhengzhou, Henan, in hanfu, catching the eye of Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao. What started as scattered online chats among fans exploded into a public craze. Today’s hanfu hype, after 20+ years, owes a lot to passionate fans, dedicated researchers, and a booming industry making hanfu affordable and wearable every day.

At the heart of hanfu’s revival is a quest to uncover what it really looked like across history. With some wild, creative takes out there, we’re diving into three key eras—Tang, Song, and Ming—to explore their iconic styles, unique quirks, and why they matter. You don’t have to stick to historical rules for hanfu, but knowing its true roots helps you wear it with confidence and inspires fresh designs. Let’s travel back in time!

Tang Dynasty: Bold and Glamorous Hanfu Fashion

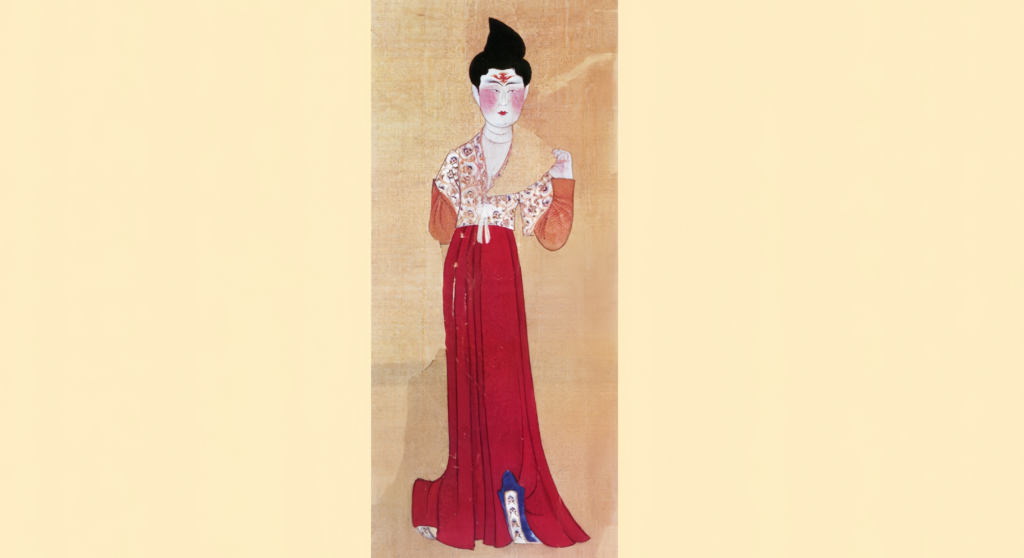

The Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) was a fashion powerhouse, blending simplicity with extravagance. Women’s hanfu featured a three-piece set: skirt (qun), shirt (shan), and shawl (pei). High-waisted skirts tucked under the chest and draped shawls were staples, while men favored round-collar yuanling pao robes.

After the short-lived Sui dynasty, the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) took over, keeping the late Northern Dynasties and Sui’s fashion vibes. Women’s hanfu was a classic three-piece set: skirt (qun), shirt (shan), and shawl (pei). Whether you were a commoner or noble, these were wardrobe staples. The style was simple: tuck the shirt into a super high-waisted skirt, often near the chest, and drape a shawl over your shoulders. Shawls started trending in the Northern and Southern Dynasties but became a Tang must-have. Men’s fashion? Less flashy—yuanling pao (round-collar robes) ruled the entire Tang era.

The Tang Dynasty Hanfu fashion’s bold aesthetics set the stage for Hanfu’s evolution.

Early Tang: Sleek and Subtle

In the early Tang, women’s hanfu was slim and understated. Narrow-sleeve shirts, colorful striped skirts (jianse qun), and soft makeup defined the era. Paintings like The Carriage Procession show palace maids in practical, elegant outfits, embodying early Tang’s refined aesthetic.

Wu Zhou Era: Bold and Bare

Under Wu Zetian (690–705 CE), hanfu fashion got bold with tanling zhuang—low-neckline tops with plunging V-necks. These open cross-collar tops, seen in Tang figurines, rivaled modern evening gowns. Shawls widened, and shirts were worn loose, showcasing confident styles.

Tang Trends: Women in Men’s Clothing

Another Tang fashion flex? Women rocking men’s outfits. A famous story from New Book of Tang tells of Princess Taiping, Wu Zetian’s daughter, showing up to a banquet in a purple robe, jade belt, and folded cap, dancing for her parents, Emperor Gaozong and Wu. This cross-dressing trend was hot from early Tang, though it faded a bit by the late Tang.

Peak Tang: Yang Guifei’s Extravagance

Tang fashion hit its high point with a thirst for glamour, led by none other than Yang Guifei. Emperor Xuanzong had 700 tailors crafting outfits for his beloved concubine and her crew, mastering weaving and embroidery. Styles, especially hairdos and makeup, changed fast—sometimes every few years. Classic Tang makeup? Think bold brows, lip dots, floral forehead decals (huadian), blush, and cheek dimples (yanye). From early Tang’s restraint to Wu Zhou’s boldness to late Tang’s over-the-top luxury, Tang women always kept fashion fresh and stunning.

Tang’s open, multicultural Chang’an fueled this diverse hanfu fashion. For more, visit China Highlights.

Why so diverse? Tang’s 300-year run saw booming trade, a sprawling empire, and a million-strong cosmopolitan Chang’an. This open, multicultural vibe let Tang folks experiment wildly with fashion, creating a dazzling array of looks.

Song Dynasty: Elegant and Minimalist Hanfu

Want a peek at real Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) hanfu? Head to the National Museum of China’s “Ancient Chinese Costume Culture Exhibition.” There, a restored Song male figure rocks a purple gauze long-sleeve official robe (gongfu) down to his ankles, hands clasped in respect. Underneath, a light blue beizi (long jacket) peeks out with wide sleeves and subtle plant patterns, paired with a red belt with gold lychee motifs and black shoes. Next to him, a Yuan dynasty figure in a yellow-brown robe looks totally different, highlighting Song’s unique style.

This outfit comes from artifacts in the Zhao Boyun tomb (Southern Song, Huangyan, Zhejiang), a descendant of Song founder Zhao Kuangyin. His tomb had minimal treasures—just a jade disc, crystal disc, and some agarwood—showing Song’s chill, minimalist vibe. Zhou Yang, deputy curator at the China Silk Museum, worked on preserving these textiles and was struck by their simplicity. “Song people buried only their favorite things, no gold or silver,” she noted.

One standout? A cross-collar lotus-pattern gauze robe (jiaoling sha pao). “It’s so light and sheer,” Zhou said. After cleaning, its wide sleeves and sides revealed delicate lotus patterns, pure Song scholar aesthetic. Picture Zhao Boyun in this breezy robe, his beloved jade disc at his waist, peeking through the gauze folds—total heartthrob vibes.

Song : Beizi for All

Song men’s hanfu saw a game-changer: the beizi, a cross-collar jacket with side slits. It was even bigger for women. By late Northern Song, this straight-collar, open-front, knee-length jacket with narrow sleeves and long side slits became a palace staple for empresses and concubines. A shorter version, the shan (shirt), followed suit, ditching the wide, Tang-style sleeves for a sleek, modern cut. See it in the painting Yao Tai Music Steps, where three noble women in knee-length beizi look tall and graceful.

Historian Shen Congwen called Song women’s hanfu “fashion-forward,” noting its “modern” feel. Take the Chayuanshan Song tomb (Fuzhou)’s wide-leg pants, made of light floral gauze (hua luo). Their secret? The pant legs are fully open from waist to hem, worn over silk leggings for a breezy, avant-garde look.

Professor Zhang Ling from China Media University recreated these pants, and her students were shocked: “Southern Song was that bold?” This openness wasn’t a one-off—by Southern Song, beizi and shirts were worn open, with bandeau tops (moxiong) peeking out and simpler skirt pleats, reflecting women’s freer lifestyles and rising status.

Song hanfu’s elegance shines in its muted, refined colors. Without surviving fabric hues, we turn to Song poetry for clues: “blue shirt with apricot skirt,” “lotus silk sleeves with tulip scent.” After Tang’s bold palette, Song leaned into softer, less saturated tones—think pastels and mid-tones. Layering these shades created a warm, graceful look, pure Song charm.

Ming’s Vibrant Splendor

For hanfu researchers, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE) is a goldmine. Why? Tons of well-preserved artifacts, unlike archaeological fragments, offer clear shapes, colors, and patterns.

The biggest stash? The Kong Family Mansion in Shandong, home of Confucius’ descendants (Yansheng Dukes). Their collection, spanning Song to Republic eras, survived political upheavals like “clothing reforms.” In the 1980s, the Qufu Cultural Relics Committee found over 100 Ming garments in camphorwood chests in the mansion’s attic—jackpot!

Ming Women: Jackets and Mamian Skirts

Ming women’s everyday look? Jacket (ao shan) on top, skirt (qun) below—aka “two-piece dressing.” For formal events, they’d wear round-collar robes (yuanling pao) or large gowns (da shan), but the jacket-skirt combo was the go-to.

The star skirt? The Mamian qun (horse-face skirt), named for its flat, protruding panels resembling castle wall turrets (Mamian). A standout from Kong Mansion is a green floral gauze Mamian qun with five-clawed dragon patterns, a high-status imperial gift. Its weave blends makeup-like embroidery (zhuanghua) and gold threading, screaming luxury. The onion-green hue matches skirts in Emperor Xianzong’s Lantern Festival Painting, a trendy Ming color.

Ming jackets got a twist by the mid-Ming: shuling (stand-up collars). Beyond traditional round or cross collars, stand-up collar jackets—either open-front (duijin) or wide-front (dajin)—became women’s faves. These collars were perfect for showing off buttons, made from imported Central and West Asian gems thanks to Ming’s bustling trade. Fancy women could sport up to seven gold or gem buttons on an open-front jacket, flexing their wealth.

Why stand-up collars? Two theories: the mid-Ming’s mini ice age made higher collars cozy, or rising neo-Confucian modesty rules pushed stricter coverage, especially by late Ming, when body taboos got intense.

Ming Men: Dao Robes Rule

For Ming men, nothing says “iconic” like the dao pao (Taoist robe). Originally for Taoist priests, it became a scholar’s staple. Picture a straight-cut, cross-collar robe with a wide front flap, white or plain collar trim, and “hidden flaps” (anbai) to cover side slits, keeping inner layers discreet. Pair it with a silk sash, thin belt, or wide belt. Kong Mansion’s blue floral gauze dao pao is a gem, dyed with indigo and woven with cranes, peaches, pomegranates, and auspicious patterns. It’s easy to imagine a Ming scholar rocking this, looking wise and stylish.

Ming dyeing was next-level, per Song Yingxing’s 1637 encyclopedia Tiangong Kaiwu. It lists 28 colors from plant and animal dyes, with one dye making multiple shades or one shade needing multiple recipes. Red was the Ming’s signature, with six types: crimson (dahong), lotus, peach, silver, water, and wood red. Crimson, dyed with safflower, was the boldest. Kong Mansion’s crimson floral gauze round-collar robe with cloud-crane patches still pops, proving Ming dyes’ lasting vibrancy—perfect for your red hanfu interest!

Ming’s Grand Legacy

Ming hanfu is the ultimate “greatest hits” of Chinese fashion. It blends Zhou, Han, Tang, and Song styles, thanks to Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang’s top-down clothing system, setting strict rank-based rules. Add in epic advances in weaving and dyeing, and Ming’s mix of rigid structure and technical flair created a unique, dazzling era. From Mamian qun to dao pao, Ming hanfu is vibrant, practical, and timeless.

Conclusion

Hanfu fashion’s journey from Tang’s dazzling glamour to Ming’s majestic splendor is a testament to its timeless appeal. Whether you love Tang’s low-neckline tops, Song’s breezy beizi, or Ming’s vibrant Mamian skirts, 2025 is the year to embrace hanfu. Which era’s style is your favorite? Share in the comments! For styling tips, visit Fashion Hanfu.

Responses